She’s the centrepiece. At her base, a sea of ferns and fronds. Mist gently rising. Behind her, a floor to ceiling soft brown velvet curtain. People are queueing for hours to see her. They are waiting to spend a moment, before or during her unfurling. Anticipating proximity, anticipating her smell.

I’m 800 kilometres away, watching her on the livestream. I watch as faces come and go. People invariably photograph her and photograph themselves with her. Many pause and turn to face the camera that captures the livestream. They wave and pull faces. The livestream goes for days, but it is only on the last day that she opens up.

I’ve been thinking about what it is to have a digitally mediated relationship with a plant. The blossoming of the corpse flower (Amorphophallus titanium) was a big moment. It was the first time in fifteen years that this particular plant had flowered; the first time in fifteen years that Sydney’s Botanical Garden had played host to a flowering corpse flower.

The staff at the gardens affectionately named the plant Putricia, a portmanteau of Patricia and putrid and a reference to the smell this kind of flower emits upon unfurling, like rotting flesh. Experiencing the plant remotely, through my eyes only, I felt an augmented sense of what Eva Hayward calls haptic vision — or “fingeryeyes.” This is the idea that we can touch through seeing and gain a kind of impression — a sense — of the non-human other.

I’ve never been in the presence of a blossoming corpse flower. I’ve never breathed in the scent. But through my computer screen I could experience Putricia’s soft velvety folds, her firm but wilting spike. I could feel close to her.

Livestreams to get us closer to the more-than-human world have been around for a while now. Since the early 2000s, so-called ‘nest-cams’ have allowed online viewers to watch as peregrines lay, sit on, and hatch their young. These devices gave us insight into the hidden personal lives of the birds, allowing people to develop knowledge of and affective connections to them. Geographers William Adams, Adam Searle and Jonathan Turnbull argue that such digitally mediated encounters with wildlife can and should be considered “authentic,” with real ramifications for how people think of their role in and relationship to the more-than-human world. The effects of the nest-cam are twofold: they generate new knowledge about the species itself while simultaneously enabling new forms of human-environment intimacy.

Sometimes these intimacies extend to specific identifiable individuals, rather than just happening at the species level. For instance, during Fat Bear Week — which normally falls in October — people vote for their favourite bear among those selected by the rangers at Katmai National Park and Preserve in Alaska. Viewers can tune into “bear cams” throughout the season, and vote for their favourite bear during the actual week. Nest-cams and bear cams offer humans access to the lives of these wild creatures without them knowing they are being observed. With new and emerging technologies, the possibilities for relationships with specific animals expand, as evidenced by new work to design facial recognition software that can identify bears at the level of the individual. And then there are the captive zoo animals that have become social media sensations, like Pesto the penguin and Moo Deng the pygmy hippo, both of whom captured the attention of social media users around the world.

Whether the subject is captive or in the wild, livestreams of charismatic fauna have become a common way for environmental managers and conservation biologists to generate interest in and concern for threatened species. There is a taken-for-granted wisdom that by offering the public a window into multispecies worlds, people will begin to care avidly about biodiversity loss, conservation objectives, and sustainability goals. This feeling pre-dates livestreaming by decades and may hold some truth. In the 1970s, recordings of whale songs made by cetologist Roger Payne and incorporated into a recording by musician Judy Collins did, in fact, have an enormous effect on public attitudes towards whales and whaling. It is easier to care about something if we can sense it.

As well as through livestreams, the more-than-human world has become more visible to us through surveillance technologies, like trail cameras, GoPros, and drones. These can engender what geographers Erica von Essen and colleagues call a “top-down logic of wildlife surveillance” that comingles with biosecurity rationales seeking to control humans as well as non-humans, ultimately reproducing centralised forms of biopower.

Even in this early phase of the so-called Digital Anthropocene, it is clear that surveillance technologies used to observe wildlife can have a punitive effect. Take Los Angeles, where concerned citizens have been reporting sightings of coyotes via the social media application NextDoor. In this region, the coyote is at once a native animal and a predator that poses a risk to people’s beloved pets. On NextDoor, its online echoes have taken on a life of their own. As Niesner and colleagues write, “a sighting of a real coyote can suddenly and vividly animate a cloud coyote, which in turn can convince hundreds of commiserating neighbours that they too have seen a real coyote, even if they have not.” These “sightings” have given rise to vigilantism, with community groups popping up and seeking to remove coyotes from cities in ways reminiscent of White middle-class anxieties leading to the policing of people deemed to be undesirable.

Yet these technologies — entwined as they are in the logic of biosecurity — also allow the more-than-human world to become “more abstract and intimate to us; more proximate and distant.” That is to say: knowable, observable, but always mediated through the prosthesis of technology. Just as new technologies to apprehend wildlife can function as a conduit to air and exaggerate pre-existing anxieties about safety and porosity (in terms of biosecurity, biodiversity, or the welfare of pets) so, too, can they generate new insights and new kinds of relationality. And when it comes to plants, livestreams offer us something interesting.

The term “plant blindness” refers to the phenomenon of plants escaping our notice because we are not attuned to them. It’s possible to rectify this with a little bit of care and consideration, and just enough knowledge to enable us to distinguish between plants. Once you have made the effort to be able to identify a species you previously viewed as part of an undifferentiated, green background haze of your field of vision, you start to see it everywhere. Now you notice its true incidence. Now you realise that this plant is exceedingly common, or that it’s not, and a sighting becomes special and momentous. But part of what makes plants difficult for us to see, apprehend, and take into consideration, is that they move at different timescales to humans.

Truly seeing plants means tapping into their heterotemporalities, or what Jason Margulies has termed “phytotemporalities.” Often, plants move both too quickly and too slowly for humans to appreciate. Take the corpse flower. For fifteen years she exists without flowering and then, suddenly she blooms — but only for 24 hours. In her natural habitat, this may be easy to miss. In a botanical garden, where she is continually observed by people aware of her endangered status, the flowering may be closely watched, recorded, and broadcast to the world. It is awaited with excitement. With the addition of livestreaming, many more people than ever before can experience this previous event.

The livestream intervenes in the plant’s fast and slow phytotemporality. It allows a digitally mediated window into this special moment in time, in a way that can be said to slow it down. We are given substantial warning about when the blooming is likely to happen, and we are able to watch as the event grows nearer. The spectacle of Putricia’s flowering is observed by many thousands of people, in a setting that is both intimate and distant. Sitting at home, we are able to observe the event for much longer than the people who line up to see her in physical form, and yet we are also distant, linked only through a screen and fibreoptic cables and the energy grid and the whole other host of things that make livestreaming possible. We can observe her gradual changes. We can watch the people who care for her come and go, tending, sampling. If we want, we can share our observations and feelings for Putricia in the comment section with the other viewers, and be part of an ad hoc community assembled just for her.

*

Later, I watch a timelapse of her blooming. It is beautiful, arresting, but it does not have the same effect on me as watching her livestream in real time. Slow but fast. Close but far. I can’t smell her, but I can touch her with my very own fingeryeyes.

These technologies bring up closer to the more-than-human world in new ways. With livestreams we are able to see, close up, the lives of more-than-humans unfolding in front of us — whether they are newly hatched peregrines or blossoming corpse flowers.

Though digitally mediated, these intimacies are real. At the same time, these new technologies are folded into existing regimes of biosecurity and biopower. Surveillance technologies offer new possibilities and affordances for conservation, enabling more comprehensive ecosystem monitoring with potential benefits for environmental management, while at the same time reaffirming structures of power.

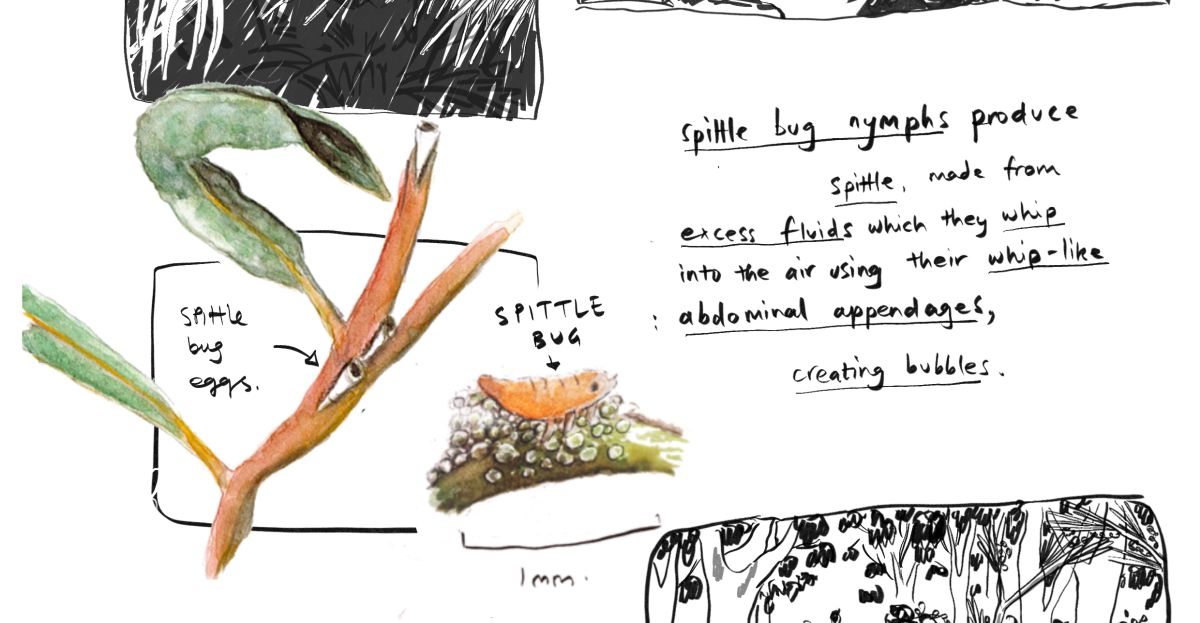

Original illustration by Sofia Sabbagh

This piece is sponsored by CoPower, Australia’s first non-profit energy co-operative. To find out more about CoPower’s mission, services, and impact funding, jump online at https://www.cooperativepower.org.au/ or call 03 9068 6036 today.