Water is an elemental force that may be subtle or powerful, trickle gently, soothe or roar, and sweep all before it in a deadly trajectory. It comprises over ninety per cent of our bodies, and moves us, consciously or not, with the tides. For artist Judy Watson, water sits at the heart of her forty-year practice. It is her subject, material and inspiration.

Watson harnesses and choreographs water, and has worked with its qualities since her beginnings as a printmaker. She then moved into pigment-soaked, layered canvases within which the viewer may drift amongst floating forms, part of a broader landscape and geography of belonging. Watson worked in this way even before she was aware of her connection to Waanyi Country in Queensland’s north-western Boodjamulla Lawn Hill Gorge, where she travelled in 1990, when she was thirty years old.

Subterranean water bubbles to the surface in this place. It is ancient; she describes it as ‘dinosaur water’. The rainbow serpent, always present in the gorge, nurtures this place although, if the water is poisoned or dries up and she is forced to leave, the area will dry out, barren without its life-giving force.

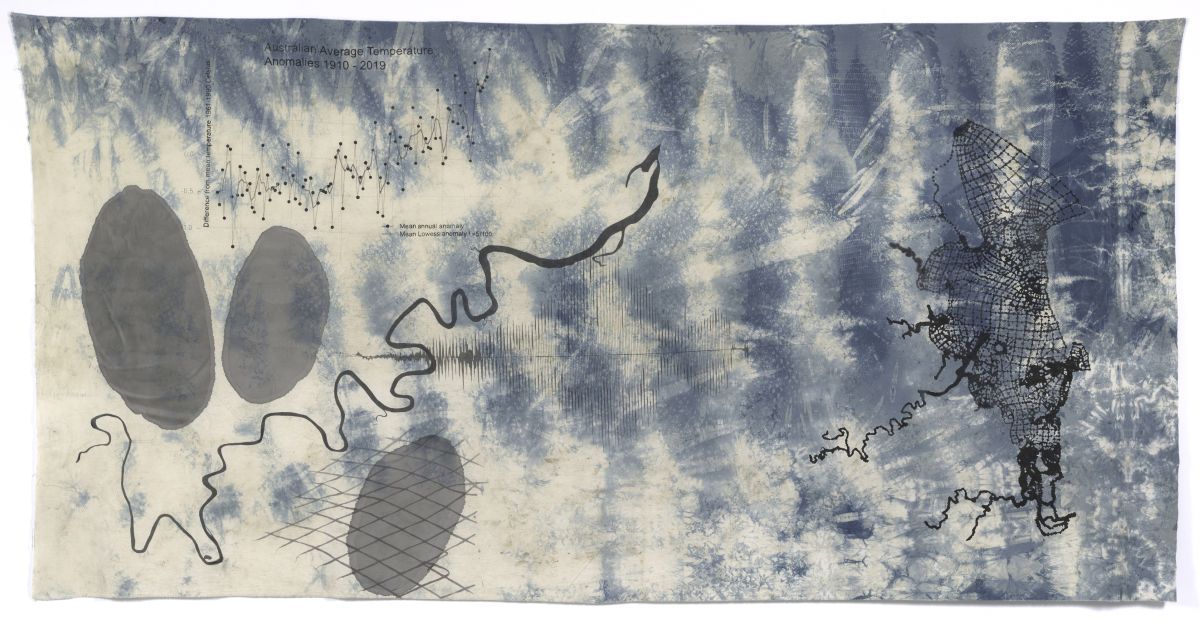

mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri / tomorrow the tree grows stronger opened on 23 March at the Queensland Art Gallery and is titled after a poem written in Waanyi language by Watson’s son, Otis Carmichael. It is Watson’s largest show, containing 120 works. Her fluid, unframed canvases line three galleries, steeped in watery pigment, created with paint and amorphous shapes, embedded by the dancing feet of her friends and family. They are seductively beautiful, with colours stained deep into their fabric, simmering with intensity, and are overlaid with translucent images — shells, shapes, markings, heads of people and animals — that float out and into a viewer’s consciousness. But they also pack a punch, with a commitment to expressing often uncomfortable truths. Watson draws from her identity and family histories with stories of universal dispossession, environmental awareness, feminism, and a sense of simmering injustice about the Indigenous materials that remain in the archive, collected without permission.

The canvases line spaces that also include her prints, films, sculpture and references to the art she has made for public places. Each of the exhibition’s three areas are situated within and adjacent to the Queensland Art Gallery’s water mall. This space was designed in 1982 by architect Robin Gibson to broadcast the Queensland light, with vistas to the adjacent Brisbane River/Maiwar, which winds, a huge brown serpent, through the city. The water mall echoes and amplifies Watson’s work, as her work does this space.

The architecture was designed to democratise access to art for everybody. Equally, Watson’s impetus since the beginning of her career has been to bridge the divide between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Watson came early to a way of art-making for urban-based Indigenous artists, a mode that delivered political truths as integral to an aesthetic. Such avenues are taught at university now, and are well understood, but for Watson and some of her contemporaries — notably Tracey Moffatt (born 1960), Gordon Bennett (1955-2014), and Fiona Foley (born 1964) — forty years ago, it was necessary to blaze this trail. In the 1980s it was art from the desert which was sought after. Now Watson is recognised as one of Australia’s most significant voices, having received the most prestigious awards available to contemporary artists. These include representing Australia at the 1997 Venice Bienniale (with Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Yvonne Koolmatrie) and winning the Clemenger Award (presented by the National Gallery of Victoria) in 2006.

What is remarkable, when considering Watson’s work since the 1980s is the consistency of her motifs, and the commitment she exhibited so early in her practice. In the intervening decades, many truth-tellers have emerged amongst the newer generations, but Watson’s journey has an emotional impct — its aesthetic seductive yet indelibly leaching its stories in a manner informed by science, ecology, feminism and the archive. As Ted Snell writes, “That sense of humility and her determination to make a difference within a community remain as core principles in her work.”[1]

The impact on the earth of a changing climate is conveyed in a manner that weeps its grief through graphs of landscapes, filtered into work that narrates its meaning with titles, like spot fires, our country is burning now (2020).

In three dimensions we bump up against horrific stories, conveyed with a particular touch. 40 pairs of blackfellows’ ears, lawn hill station (2018) illustrates a narrative from the archive, Aboriginal ears cast and pinned to the wall; these might well have included her own ancestors. The prints tell other family stories of injustice and sadness, like her artist book under the act (2007) which draws on letters written to Queensland’s Chief Protector of Aborigines for permission to marry.

Waston has witnessed and documented Indigenous objects seen in international museums removed from communities, leading to the works our skin in your collections, our bones in your collections and our hair in your collections (all 1997). These may be uncomfortable histories, but the way Watson gently, indelibly, conveys her message through an aesthetic that is beautiful, while speaking to the water in our own bodies, makes an emotional swell that is truly masterful.

Like all of Watson’s enterprises, the exhibition is a joint effort involving friends, family, and colleagues, always becoming more than the sum of its parts. There is poetry here, from Otis’s title, in the titles of the works (Watson’s words that trickle out over the walls), in the deckled edges of the canvases which speak to the water in their transformation, and the prints and posters with which she began her practice. The media preview began with a demonstration of whip-cracking, sound snapping like heartstrings. It becomes impossible to see this work without thinking about fragility, the rainbow serpent in the gorge, the health of the continent, ongoing injustice to Indigenous peoples, and the race we are all in to survive. Watson’s work leaves an indelible mark on the psyche.

[1] Ted Snell quoted in Judy Watson and Louise Martin-Chew, judy watson: blood language, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2009, p.14.

Image: Judy Watson / Waanyi people / Australia b.1959 / moreton bay rivers, australian temperature chart, freshwater mussels, net, spectrogram 2022 / Indigo dye, graphite, synthetic polymer paint, waxed linen thread and pastel on cotton / 247 x 488cm / Purchased 2023 with funds raised through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation Appeal / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Judy Watson/Copyright Agency / Photograph: N Harth © QAGOMA