The politics of memory — who and what we remember, who and what we forget — and the nexus between power and those events which, no matter how disconnected, are constructed as a nation’s “history”: these themes echo strongly in the anticolonial work of Swiss-Haitian artist Sasha Huber. Here, work is not a metaphor. “It’s not art”, Wiradjuri artist Karla Dickens says, “it’s bloody work.” Like Dickens, who salvages discarded objects such as industrial farm machinery which seem to be burdened by — or implicated in — historical racism, there is nothing idle about Huber’s approach to artmaking. When she is not engaged in a confrontation with power, of talking back, Huber is engaged in repair work. Her partner, and fellow artist, Petri Saarikko fairly observed that Huber is “lifting rocks from the past to build a bridge for the future.” The metaphor of hard physical labour is not throwaway or idle either — confronting power and repairing damage is emotional and intellectual work. Huber may deny it, but her practice is driven by a need to create a future in which her son can live undivided as the descendant of enslaved African people trafficked to Haiti in the nineteenth century and of Europeans who derived their wealth from slavery and dispossession.

In the process of confronting power and repairing damage, Huber creates artworks that are profound and hauntingly beautiful. The process of “softening” metal — at least to the human eye — so that it has the luxurious swirl and weft of a carpet, or the fur of a loved pet, can only be described as alchemy. With the skill and manual dexterity acquired through decades of experience, Huber has managed the optical trick with her latest series of works for Crepusculum, a joint exhibition with Saarikko. The illusion masks the brutal method she employs in the studio, not to mention the non-aesthetic — even non-art — characteristics of her medium and principal tool.

In a practice that is as unconventional as it is diverse, Huber’s key mode is performativity and a deeply embodied process. The bicultural artist situates (or implicates) herself in a struggle between history and what might be termed “non-history” — that which is excluded or denied from the active storymaking processes that constitute public history. I use the term “non-history” to describe the unremembered events and, indeed, people whose forgetting is imperative to the story of the emergent nation state, the empire or the clan — along with their histories, systems of law and belief, their cultural practices and codes of behaviour, their social, economic and political structures, their languages, epistemologies and iconographies. I am not for a moment suggesting that what I term “non-history” is not history, only that these peoples and their cultures are marginalised by the storymakers. This is a literal marginalisation here in Australia, in that those who “write” public history —professional historians, politicians, curators working in museums of history, stage and film directors, writers of fiction and the media — often consign First Nations people and their histories to the edges of the narrative as margin notes in the telling of the Australian story.

At least at the outset, this disremembering was conscious and deliberate. It brings to mind the sarcastic line “never let the truth get in the way of a good story.” Australia’s collective memory is clear on the heroism and sacrifice of the fallen and those who survived the military rout that was the Gallipoli campaign during the First World War. It is less clear on the 1928 Coniston massacre in central Australia, which was led by a Gallipoli veteran. The memory falters when “remembering” that the continent was occupied for at least 60,000 years before the British invasion and annexation that began in 1788. The amnesia really sets in when asked to recall the measures British colonialists employed to secure Australia for themselves — how they annexed a continent, dispossessed the people and stole the land. Another minor fact often gets elided in the telling of the national story: that the vast continent wasn’t surrendered or sovereignty ever ceded — two of the means by which ownership of a land mass might be transferred, overthrowing any pre-existing system of governance or land tenure. (The artist Richard Bell tells me that, in Western legal doctrine, there are three means by which a state may acquire sovereignty over sovereign territory: cession, invasion and conquest.) Nor do the storymakers confront the truth of what dispossession actually means — to make a person landless, to condemn them to walk their country like a ghost. Any mention of the litany of human rights abuses or the extent of the inhumanity that made the wholesale theft of a vast, inhospitable but populated continent on the other side of the world possible still unsettles and provokes some Australians.

In his 1968 ABC Boyer lecture series After the Dreaming — a watershed moment in national historiography debates and Australia’s intellectual life — the anthropologist W E H (Bill) Stanner punctured the conspiracy of silence around “The Frontier Wars”. Stanner characterised this forgetting or disremembering as a flaw in our national character — a blind spot, at the very least. He likened the willful myopia to a deliberate partial view from a window,

… which has been carefully placed to exclude a whole quadrant of the landscape. What may well have begun as a simple forgetting of other possible views turned under habit and over time into something like a cult of forgetfulness practised on a national scale.

This view is obscured by a pathological amnesia, aided by public history and consolidated by monuments to the “discoverer” Lieutenant James Cook, such as the one in Sydney’s Hyde Park, in effect gaslighting the black body politic. Some blackfellas — through intergenerational knowledge transfer or transmitted oral history — retain the communal memory of a massacre which their ancestors survived or witnessed but which was undocumented, denied or struck from the record. Erasing human memory without extreme physical intervention or killing is presumably neither simple nor instantaneous, although the child removal policy was an attempt to induce amnesia so that future generations might delude themselves. This refusal to see the violence and brutality deployed in the undeclared wars that ignited the Australian frontier over a 140-year period from invasion to the 1928 Coniston massacre serves a single purpose: to protect the amenity of the coloniser’s obstructed view.

Elsewhere, Stanner identifies this disremembering as “the great Australian silence” — a refusal even to hear the voices of the disremembered or their descendants, let alone listen to their grievances. The 2023 Referendum, which would have recognised First Nations people in the Constitution and legislated for a representative “Voice to Parliament”, instead amplified the dissonant voices of black conservatives such as Jacinta Nampijinpa Price. A Warlpiri and white Australian woman, Senator Price hails from Yuendumu, a community that abuts Coniston Station. Here, at least thirty-one Warlpiri, Anmatyerr and Katyetye people were killed in a series of reprisals, known collectively as the Coniston massacre, following the murder of a lone dingo hunter in 1928. (It is however generally accepted that many more were killed in the punitive raids led by Police Constable William George Murray, a Gallipoli veteran and local Protector of Aborigines.) At the height of a toxic, rancorous and unedifying national debate , Senator Price — the leading proponent of the “no” case and the Federal Opposition’s Indigenous affairs spokeswoman — declared that Aboriginal people had entirely benefited from colonisation, citing running water and readily available food as proof. She went further. Asked at the National Press Club to clarify her position, Senator Price flatly denied that there were any ongoing negative impacts of colonisation. In Price’s view, to accept this premise implies that “someone else” is responsible for the lives of Aboriginal people, ascribing victimhood and depriving them of their agency: “The worst possible thing that you can do to any human being,” she demurred, to spontaneous applause from a band of supporters, including her parents. Indigenous Affairs Minister Linda Burney later characterised those statements as a “betrayal”. But Senator Price’s self-interested populism and dog whistle politics evidently struck a chord with many Australians,

who emphatically voted the Referendum proposal down 60 to 40 — preferring instead the amenity of their obstructed, partial view.

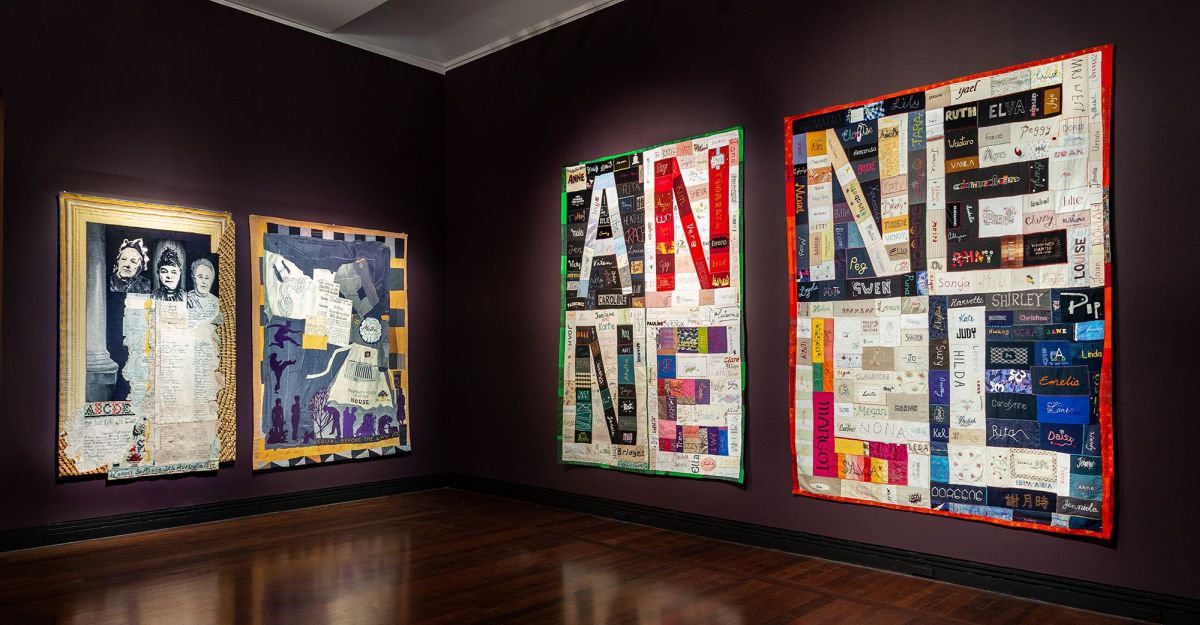

In a dramatic attempt to expose the blind spots in the public history that she inherits as a Swiss, Sasha Huber has renamed a mountain in the Alps and “unnamed” a glacier in Aotearoa New Zealand. Huber is mimicking the proprietorial colonial impulse to rename landforms and other physical features that possessed Lieutenant James Cook as he mapped the coast of eastern Australia in 1770, except she is overwriting the name of a countryman who left a dubious legacy — the Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation in the southern United States and by extension, Apartheid in South Africa. There is also a performative aspect to Huber’s studio practice in Helsinki. Repetitively and deliberately, she fires a high-powered, semi-automatic nail gun — both an indispensable part of a tradie’s kit and a weapon with the potential to maim and kill — to produce startling rectilinear images on plywood. That Huber sees the repetitive act in biomedical terms as a form of repair, to reconstitute something that is broken, is made clear when she describes her process as “stitching the colonial wound”. The only exponent of this stapling method, Huber also discovered the technique and the latent aesthetic possibilities of an extremely unlikely medium.

Huber’s work includes portraits of subaltern heroes, such as the enslaved Congolese man Renty and his daughter Delia, who unwillingly sat for daguerreotypes in Antebellum South Carolina in 1850, and the writer James Baldwin, for whom the artist and I share a great affinity. A recurrent theme in her work, Baldwin — who was living in self-imposed exile in France — retreated to Switzerland to write in the early 1950s after nearly suffering a breakdown. In his essay Stranger in the Village, the African-American writer observed how the racism he experienced in the isolated rural village of Leukerbad was fundamentally different to that he experienced in the United States, the country of his birth. (Huber’s joint exhibition with Saarikko opened to the public a day after the centenary of Baldwin’s birth.) Like Baldwin’s and mine, Huber’s feelings about the country she was born into — in a fulfilment of history itself in waves of forced and voluntary migration, and the traffic of love and family through unknowable misery

and suffering — are complex.

Huber’s subject is not always human. In another series of works, and in the limited range of available colours, she recreates the wing markings of a Monarch butterfly — a species whose migration north from the equator mirrors her own and that of her more recent ancestors. (Miraculously, the descendants of the migrating Monarch butterfies will return to the precise spot in the mountains of central Mexico where their antecedents emerged from the chrysalis several generations previously. A new cycle begins.) In this series of new works, Huber “returns” to an early form of long-distance communication that cues a personal memory of her maternal grandfather: Georges Remponeau, a leading artist, teacher and mentor from Port-au-Prince who first went to the United States in 1942 to study industrial design and later emigrated. From his basement in the New York borough of Queens, Remponeau — a radio enthusiast — would tap out messages on a device in the system of dots and dashes known as Morse code.

Huber’s unequivocal messages telegraph her allyship and her distress — in dots coated with gold leaf and dashes in burnt wood. SOS. LAND, BACK, NOW. The dots, with their swirl and weft, are a homage to the yellow ochre-coloured sun that is the key design element of the Aboriginal flag designed by Luritja man Harold Thomas in 1971. The burnt wood evokes the Black Summer bushfires that raged across eastern Australia in 2019−2020, at least for me. Huber is no stranger to Australia, nor its racial politics. She met the Kokatha and Nukunu artist Yhonnie Scarce when they both exhibited their work at the 2014 Biennale of Sydney. Along with Scarce and myself, Huber was one of several international artists invited to participate in the 2015 Mildura Palimpsest Biennale, curated by Jonathan Kimberley. Over a four-week period in March−April 2015 we “unmade” the map of European “discovery”, or at least reversed its trajectory by visiting three World Heritage sites across three continents.

Our origin was Lake Mungo, in south-western New South Wales — the terminal lake in a system that once teemed with human and animal life before it evaporated 15,000 years ago. Mungo is also the site where the oldest human remains yet found on the Australian continent were unearthed, in 1968 and 1974. At Mungo, Huber listened attentively as traditional owners explained how Mungo Man and Mungo Lady emerged from the windblown sands of the lake in separate archaeological digs, 500 metres and six years apart. She heard how stories were embedded in footprints and animal tracks across the surface of the drying lake over thousands of years — sites known as trackways. Huber was deeply moved by the experience, despite being temporarily cut off from telecommunications with Saarikko and their four-year-old son.

Huber wrests with history itself — and the politics of memorialisation — in her ongoing project to draw attention to the legacy of the Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz, who emigrated to the United States in 1847. A Harvard professor who proposed segregation before it became official policy in the United States, Agassiz developed theories emphasising white supremacy and “racial hygiene” that prefigured Apartheid and Nazism. A member of the transatlantic committee Demounting Louis Agassiz, Huber ascended the summit of Agassizhorn on the border of the Swiss cantons of Berne and Valais in 2008. Atop the mountain, at an elevation of 3946 metres, Huber affixed a metal plaque bearing the name and image of the enslaved Congolese man Renty, who was living in bondage to a slaveowner in South Carolina in the mid-nineteenth century. Symbolically, Huber renamed the peak Rentyhorn.

The crystalline image of Renty — an early daguerreotype — was one of fifteen commissioned by Agassiz and taken in a photographic studio in Columbia, South Carolina, in 1850. There, an unwilling Renty was obliged to take off his clothes — no doubt a confronting experience for an enslaved black man in the United States at the time. Worse still, Renty’s daughter Delia was subjected to the same humiliation. The daguerreotypes were supposed to prove the racial inferiority of Africans but were only shown once by Agassiz. Apparently lost afterwards, the photographs — in box cases lined with velvet — resurfaced in an attic of Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in the 1970s. In 2019, the descendants of Renty and Delia brought legal action seeking the “return” of the daguerreotypes, alleging “wrongful seizure, possession and expropriation” by Harvard. A court later ruled that, according to established principles, the family had no property interest in the images, which remain in the custody of the museum. In an act of repair, Huber presented the family with her portraits of Renty and Delia. However, their naked bodies were cloaked in silver staples, producing an icon-like 3D effect.

In the colonial project, it is the totality of the systems, codes and structures of the disremembered that is subject to the process of forgetting — the inviolate corpus, its armature and flesh. The invader, coloniser or expropriator will retain only as much of the subaltern’s corpse as points to the invader-coloniser’s intellectual, moral and physical superiority. A dismembered limb or eviscerated organ — a language or an artefact — is no threat to the integrity of the primary corpus. Such curiosities can indeed serve a purpose in the domination and subjection of any remnant population not yet subsumed into the primary corpus, by genetic or other means. At the peak of the assimilationist era in Australia, a propaganda image of an Aboriginal woman with her light-skinned daughter and white-passing grandson popularised the notion of “breeding out the black” — which was, to be blunt, genocidal in intent. The image was published in 1947 by the former Chief Protector of Aborigines’ and Native Affairs Commissioner in Western Australia, AO, Neville in the deeply racist tract Australia’s Coloured Minority, in which he set out the assimilationist agenda and the argument for biological absorption.

A bureaucrat who exercised extraordinary power over the lives of those he “protected” and proponent of eugenics, Neville could have been Agassiz’s successor except that the former believed miscegenation, rather than segregation, would ease the white man’s burden. A key plank in Neville’s strategy, designed to erase collective memory and group identity, was the removal of biologically “mixed” Aboriginal children from their families. At a conference of state and territory authorities in Canberra in 1937, Neville articulated the genocidal intent that motivated his administration of Aboriginal affairs in Western Australia by posing a rhetorical question:

Are we going to have one million blacks in the Commonwealth or are we going to merge them into our white community and eventually forget that there were any Aborigines in Australia?

From his appointment as Chief Protector in 1915 until he retired as Commissioner in 1940, Neville presided over the forced removal of many thousands of Aboriginal children. Although the policy and his administration inflicted incalculable harm, his strategy for biological absorption was an abject failure.

The disposability of the Other is a key characteristic of racism and a core belief of its logic. This myth apprehends the relative value of human life and judges that of the Other to be inherently less valuable. It persists in the way the news media might cover the deaths of those the West considers disposable — and thus, the “weight” it lends to a particular story: for example, the moral equivalence between four rescued Israelis versus the hundreds killed in the IDF raid on the Hamas stronghold where the hostages had been detained. The myth of disposability was no doubt mobilised by slave traders to justify the wholesale human tragedy that unfolded over hundreds of years, implicating Huber’s ancestor, a child who was transported to Haiti in the eighteenth or nineteenth century. I say tragedy, which for me has the air of something inexorable like the tides, except this was a man-made disaster — a disaster in which I am implicated. In roughly the same time period as Huber’s, a maternal ancestor of mine was trafficked from West Africa to the Caribbean island of St Vincent via the Middle Passage, the route taken by an estimated 12.5 million enslaved people over 400 years.

Negligible value attaches to the cultural production of a disremembered people, and their systems and structures, languages etc, including any intellectual capital they share. In some cases, monetary value is attached to their material culture, and some of their artefacts may acquire the status of a commodity (such as the bronzes looted by the British during their 1897 punitive expedition to the West African kingdom of Benin, or the canvases of Emily Kam Kngwarrey or Rover Thomas or the barks of John Mawurndjul). Just as negligible value might be attached to their epistemologies or languages, the collective experiences, cosmologies and imaginaries of the disremembered, racialised Other gathered over millennia can be denied, or characterised as mythology, falsehood or nonsense. In the suspension of reality, there is chaos and the disremembering — Stanner’s forgetfulness — can lead to self-delusion. It is possible for a passerby to accept a monumental lie such as that incised into the base of the Cook statue in Sydney’s Hyde Park — a proposition that denies that the land was ever inhabited, or more damagingly, that those inhabitants could be considered to be human.

Not only do passersby swallow the lie today, but 146 years ago — when the statue was erected — the lie was wholly accepted by the mason who chiselled the granite to incise the letters to make up the words that would form the lie. The artisan who finished the lie, painting the intaglio of the letters that make up the lie in gold leaf, believed it too. Today, the artisans responsible for maintaining the statue and the integrity of the words must presumably tend the lie, refreshing the gold leaf. The lie reads, bluntly: “Discovered this territory.” Such monuments are so obscenely visible that, for many of us, they disappear. The latent power, symbolism and meaning of Cook’s statue is made visible when the monument becomes a flashpoint. A site of contestation on January 26 and during the Black Lives Matter solidarity protests at the height of the pandemic in 2021, the monument is rendered utterly visible when it is defaced or vandalised or encircled by a ring of mounted police in riot gear. When the vandalism extends to permanent damage — a symbolic decapitation involving the use of an angle grinder hooked up to a generator for example, like that seen on the St Kilda foreshore of Narrm Port Phillip Bay in 2024 — there is a rupture in the body politic that demands our attention.

The weight of history bears down on people such as Huber and me. The burden is inescapable, and it has the very real capacity to limit our potential and that of the generations to come in both our families. The oracle James Baldwin spoke of the active storymaking processes that led America to disown him. “All that can save you now is your confrontation with your own history … which is not your past, but your present,” he said, and the same could be said of Switzerland or Australia. He went further: “We carry our history with us. We are our history.” Oodgeroo Noonuccal expressed the same ideas, of the contemporaneity of the past and of the colonised or enslaved body being the site of history, when she wrote in 1972: “Let no one say the past is dead/The past is all about us and within.” As the public discourse during the campaign for the failed Referendum proved, the lies and distortions that oxygenate racism still linger. Racists and mass murderers still have naming rights. And their right to be named, or otherwise monumentalised, often goes unchallenged. We have to unmake Agassiz’ house. Fold it in on itself, as if it were made of paper. All it needs is for you to light the match.

My conclusion right now, today? The past has not passed, and quite possibly, it never will pass. For me, there are many resonances in the work of Sasha Huber. I am drawn to its politics, its anticoloniality, its confrontational and performative aspects, its materiality and the aesthetic sensibilities. I acknowledge Huber for putting her body in the frame, wrestling with history and the shadow of Agassiz with only a nail gun. In the glint of thousands of staples, I see the artist’s intentionality as much as the person, thing or code being represented. Huber’s work lays down a challenge: for art itself to be a medium — a vehicle for something other than itself, a Trojan horse even. A tool to unmake the master’s house. Art must do something, or else why are you putting it out into the world?