I always hated school. Hated the teachers who beat us at the first nervous twitch of the morning. Hated sitting in a box of a room, watching the hands of a clock crawl across its own face. Hated being barked at by teachers: ‘Look this way, Birch!’ they would yell whenever I became transfixed by the river flowing outside the window. But I did love reading – always had done – and could devour a novel as fast as my old man could down a beer.

In 1970, I was in Form Two. I think they call it Year Eight these days. Richmond High School, built on the banks of the Yarra River, was only two years old but had already outgrown itself. My classmates and I were packed into a wooden portable classroom with a dodgy heater and broken windows. I was voted form captain in the first week of that year, in a supposedly democratic process. I romped in, but our ‘home’ teacher was having none of it. She vetoed the result and installed a girl with blonde plaits and a ‘junior prefect’ badge.

The girl would get on the tram after school, armed with a pencil and notebook. She would take down the names of any kid who smoked on the tram, or swore, or spat out of the open doorway, or rode the boards to dodge the fare. I don’t know where that girl is now, but I hope she lives somewhere on the other side of the river, where I’ll never run into her.

A month into the school year, in our English class, we were presented with our first novel for the year. It was Kestrel for a Knave by Barry Hines. If you don’t know the book, it’s the story of Billy Casper, a working-class kid growing up in a mining town in the north of England. Billy doesn’t have much time for school, a place where he is bullied and beaten, both by the older boys and his teachers. Billy’s home life isn’t much better, with his mum and older brother giving him the occasional kick around.

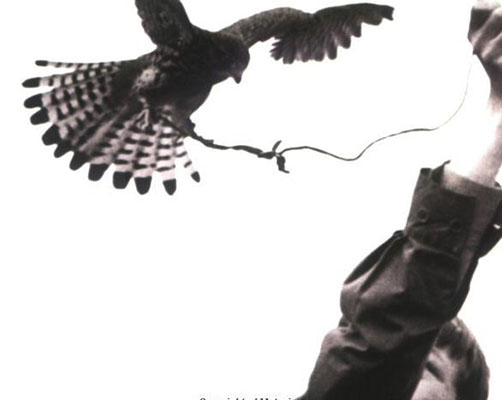

Billy discovers salvation, majesty even, when, out walking away from the slag heaps surrounding the coal town, he comes across a truly wild bird, a kestrel he calls Kes. The beauty of the novel (and Ken Loach’s 1969 film adaptation, Kes) is in this relationship between boy and bird. Billy discovers tenderness, responsibility and love, which is shockingly destroyed towards the end of the novel.

I related to Billy Casper and his life. For a time, I actually thought I was Billy: I would wag school and wander the banks of the Yarra, convinced I would be befriended by a bird as wild as Kes. I was not alone. So many of my classmates felt for Billy’s predicament and understood something of themselves in his life. I must have read hundreds of novels since that winter in that cold classroom, but I’m yet to read a book that has had such an influence on me, or that has become so integral to who I am.

My obsession with the book has become somewhat acute. For quite a few years I was determined to collect every edition and cover design of Kestrel for a Knave. I stopped at twelve copies, before deciding to free the books, giving them away to other keen readers. I have printed the book’s cover on T-shirts, and for many years now I’ve contemplated a Kes tattoo (an idea I haven’t completely given up on). And I have tried to convince my adult children that if they have babies of their own, one of them must be named Kes. So far I have two grandkids, Isabel and Archie, and I have become resigned to the fact that no baby Kes is on its way to Pa’s house.

Earlier this year, our family dog died. Ella was a beautiful fifteen-year-old staffie (who hated dog training school). She died in the arms of me and my partner, Sara. We were in grief and decided that we would not get another dog, at least not for the foreseeable future.

But then, this winter I was sent a link to a dog rescue service, and to a three-minute clip of a black-and-white Jack Russell cross. He was racing around an enclosed yard – one moment he was jumping in the air, the next sitting patiently for a biscuit. I knew immediately that this dog was mine.

He arrived the following week and immediately ran through the house, up the stairs, down the stairs, into the front yard, back inside. One night he barked at a particular federal politician on the TV – most likely saying, ‘Get fucked, Peter Dutton!’ – and then sat at my feet, took a breath and nuzzled into my leg. He came with a certificate and a name: Max. Well, fuck that too. Max is no more.

When Sara got home from work that night, the dog greeted her enthusiastically, running around in circles and licking her hand.

‘What is his name?’ she asked.

Read the rest of Overland 232

If you enjoyed this piece, buy the issue