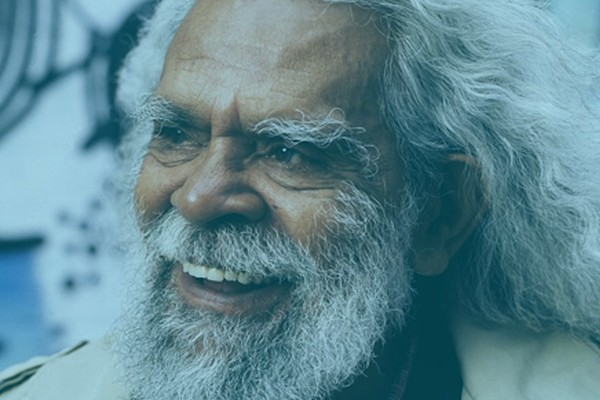

The life of Jack Charles has been told in the film Bastardy (2008) and the theatre production Jack Charles V the Crown, which has toured nationally and internationally for several years. Aspects of Jack’s life have been horrific. He is a member of the Stolen Generations, taken from his mother, family and community. Jack spent the young years of his life in institutions and foster care, where he was subject to the levels of violence and torture that accompany colonial repression. Jack’s subsequent years spent in prison are well documented, as is his remarkable contribution to Australian art and culture – in theatre, on the screen and, vitally, within the Aboriginal community.

A few weeks back I saw Jack entering the state parliament of Victoria, along with other community elders, determined to ensure that the Treaty discussions between Aboriginal people and the state government doesn’t end in another hollow symbolic gesture, driven by bureaucratic and political expediency rather than a genuine commitment to change. To see Jack among his peers, who respect him greatly, is to witness the footsteps in a remarkable journey. These are the steps of a small boy who was ripped from his community and destined to become assimilated, to disappear, to be silenced. And yet, there he was, Jack Charles, staking a claim on his sovereignty, along with others.

I worked closely with Jack during the staging of ILBIJERRI Theatre Company’s Coranderrk: We will show the country. Jack played William Barak, the Wurundjeri leader who negotiated with the Victorian colonial government in an effort to ensure the survival of his people. It was Barak, along with other senior Aboriginal people, who agitated for the sovereign rights of the Coranderrk community in the late nineteenth century. Jack’s stature, not physically, but certainly culturally, is such that each word he spoke reverberated throughout the theatre with such strength that Barak’s presence was felt throughout the room.

Jack and I had many conversations during the production of Coranderrk. We spoke of Jack’s years of incarceration, a period he is open about. We also talked about his years of recovery and the sense of responsibility he now feels and accepts as an Aboriginal elder revered by both young and old people within our community. The conversations I have had with him, both during the production and since, have provided me with an invaluable cultural education.

During one conversation, we spoke about sovereignty. It is a concept most often discussed in legal terms, as it sometimes needs to be. But for those outside the law, sovereignty – an imposed colonial concept – is a complex and contradictory notion, and in its relationship to Aboriginal lore, it is deficient in many ways. Speaking with Jack, I came to appreciate true sovereignty as an idea and practice embedded in culture, history, character and a commitment to others.

Sovereignty is the recognition of Aboriginal authority and ownership of country. But it is more than that. It is also a psychological, metaphysical and ethical way of being. Jack has said to me and others that, as an Aboriginal person, he has a responsibility to other Aboriginal people. Additionally, he has responsibility to all people. Jack provided the example that he could not walk by a person in need – any person in need – as an Aboriginal person claiming the right to Country. Although he did not say as much, I believe that Jack was articulating a clear acceptance of responsibility that comes with authority. This might seem a heavy burden for a man who has been treated with such abuse and violence. I do not believe it is so, not for Jack Charles, a man invigorated by his ascendancy.

We live in a time of great political and social challenge, in which global ‘leadership’ is dominated by rampant narcissists and opportunists, producing a culture of violence impacting on many millions of people. We also share the existential threat of ecological collapse – although too many continue to deny this sober fact. We also live in a time when our identities, including our active political identities, both empower and stifle us. In order to fight against oppression, violence and calculated ignorance, we must find ways to connect, at a minimum to support, political strategies and actions held in common. To do that, we must listen to people such as the wise and humble Jack Charles.

Read the rest of Overland 231

If you enjoyed this piece, buy the issue