‘A book changes by the fact that it does not change when the world changes.’ Roger Chartier wrote this in The Order of Books, although he knew it not to be entirely true: just a few pages earlier, he had remarked how the practice of dividing the Bible into chapter and verse, originating in the seventeenth century, ultimately modified its mode of interpretation, a fact that troubled the English philosopher John Locke at the time.

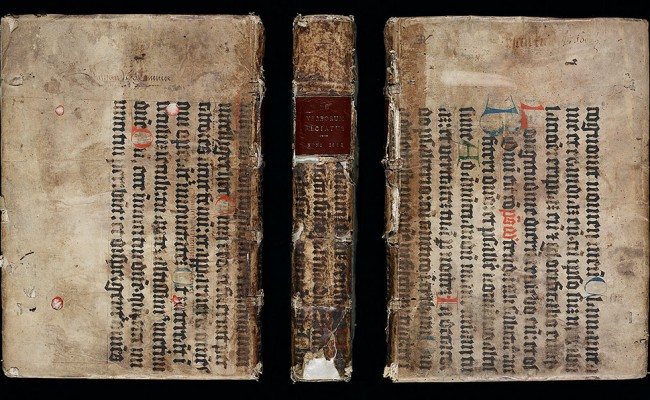

Books do change sometimes, as do texts when they migrate to new carriers. Yet they also stay the same. It’s this double nature – at once a physical artefact and, ultimately, a collection of sounds – that gives the book much of its aura and that contributes to it being an enduring unit of culture. Eternal, perhaps, at least as long as human societies exist – for haven’t the words survived? Don’t we talk of digital pages and electronic books, in spite of the radically altered nature of these new objects?

It’s the book’s capacity to resist, as well as to mark the passage of time, that draws me to it as a form, and pushes me back whenever I try to keep up with what is current and new, even to the point of frustration. I consume a fair number of contemporary articles and essays, as well as films and television shows, but when it comes to books, I struggle to muster the necessary interest in new titles. There are precious few novelists or nonfiction authors whose next work I await with genuine anticipation. And even when I dutifully buy the books I know I ought to be interested in – and that I will probably enjoy – they languish at the bottom of my reading pile, constantly fighting a losing battle against library borrowings (which, I tell myself, must be returned before the due date), or second-hand acquisitions, or much older purchases.

It’s as if I need to wait for the world to change around books, making them interesting in a new way. This may have something to do with the Italian education system and its obsession with studying the things that came before in order to properly understand the ones that came after. This pedantically chronological approach led me to encounter the ancient Egyptians and Phoenicians at every stage of my education (primary, intermediate and secondary), though my teachers never quite found the time to delve into the Second World War – an interesting omission for the country that gave birth to Fascism, I think you will agree.

With this in mind, I try to fight the ingrained habit. When, three years ago, I finally bought an ebook reader, I thought it would make me more inclined to purchase new books, especially ones I would have previously had to have shipped to New Zealand at extortionate prices. In reality, the exact opposite happened. Bamboozled and enraged by Amazon’s segregation of its international catalogues (theoretically requiring two separate Kindles, one for books published in Italy and one for those from the US), I discovered that my device unlocked vast repositories of out-of-copyright books – books I knew existed but never quite ventured into with my desktop computer. But in this new form, I could take them practically anywhere. So for some months I embarked on an apparent attempt to download the nineteenth century in its entirety. I found almost every single one of the books I plucked (almost at random) from these lists to be immensely fascinating, and a constant source of cues to pursue other readings.

I tell myself that I should change. That it’s in my professional interest, as a putative cultural critic, to be up to date in my readings, just as it was my explicit duty when I wrote my doctoral thesis. At that time, I dreaded new releases by scholars in my field, not out of jealousy or anxiety, but because they might force me to incorporate new lines of thinking into my nearly finished work. I also remind myself that old literature and criticism can be a refuge, an excuse not to engage with new, and newly challenging, ideas. All of which is true.

I am fond of an old joke of Fred Allen’s: ‘I can’t understand why a person will take a year or two to write a novel when he can easily buy one for a few dollars.’ The same could be said of new books generally. Why do we still bother? What do they say that hasn’t be said before? The answers will likely be interesting, and interestingly complicated. And while it pays to remember that it’s a joke – of course there is no retreating from culture, or pretending it is finished – the joke has some truth in it: there are millions of books in the world, all of them not changing while the world around them changes. And maybe it’s as simple as that, for me: I am not quite finished with the old books yet.