I feel more at home reading about the quintessential British experience than in books by writers of colour. Perhaps this is, in part, because of the continuing influence of the British Empire. I am Sri Lankan and, in Sri Lanka, the roots of colonialism run deep, so much so that those roots are still very visible in the education system.

I studied at an international school in Colombo, where I completed British exams (GCE O Levels and A Levels) for my secondary education. Our syllabus and teachers glorified colonialism and constantly picked texts that prioritised Britain’s heritage and history. My parents sent me there in the hope that I might have a better education and thus, a head start in life and a higher standard of living in the world.

I loved English literature but I only studied texts by white authors, poets and playwrights such as ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ by Charlotte Gilman Perkins, Tess of the d’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy, and Captain Corelli’s Mandolin by Louis De Bernieres.

We never encountered texts by writers outside of the West, though this would have had the greatest relevance to our lives. Unlike other subjects, literature made me think very deeply about my life, my emotions and the configuration of society. I found it to be a highly personal subject.

Our school introduced us to white voices, identity and history. Looking back, I never perceived my education as ‘white’. I just accepted it as the norm despite having no visible connection to the lives of the characters.

Writer Cher Tan had similar experiences in Singapore. Like Sri Lanka, Singapore had been colonised by the British. ‘It was very normal to read white authors because that was what was available,’ Cher says. ‘This was what white people do: they write books and I read them. My whole consciousness was shaped around that.’

To this day I feel more comfortable reading Brideshead Revisited or I Capture the Castle. In truth, my mind is still acclimating to the physical and emotional landscapes portrayed by writers of colour.

When it came to university, I chose Australia and chose to major in English and theatre studies.

The majority of the cohort at the University of Melbourne turned out to be white – I rarely encountered other people of colour in my course. The introductory course to my major included Arundati Roy’s The God of Small Things as an example of postcolonial literature.

The third-year courses included a semester long postcolonial subject, but this only skimmed the surface – it did not interrogate the changing social and political contexts each geographical location experienced under the British Empire.

‘Postcolonial literature’ is an umbrella term that refers to works that emerged out of the British Empire’s colonies – works that attempt to write back against the colonial project, to decolonise literature and its subjects. The genre spans so much geographical and historical context that it should be a major in its own right, in a similar fashion to postcolonial studies.

I feel as though all of my formal education has been rooted in whiteness, in some form or the other.

I feel that that the comprehension of the texts by my white tutors and lecturers was primarily intellectual. They never seemed to exude empathy for the characters or situations, and I think this is because they did not have lived experience of oppression, marginalisation or institutional discrimination. This stripped what I see as an intensely personalised major of its emotional resonance.

Writer, multimedia artist and community organiser Bobuq Sayed studied the same course as me at the University of Melbourne.

‘There was a cohesive whiteness you and I were exposed to in university when we innocently decided to study literature without realising that there was an invisible pretext to that degree which was white,’ Bobuq says.

Bobuq decided to decolonise their reading habits and focused on women authors of colour in 2017 and male authors of colour in 2018.

Like Bobuq, Cher started questioning the absence of writers and narratives of colour once she gained the language for it. In many ways, the discourse around decolonisation is only available to those who have access to academia.

Thankfully, the internet has opened many previously closed doors and has proven a brilliant tool in connecting marginalised people. Cher found a treasure trove of ‘alternative information’ online. This changed her mind-set about the books she chose – ultimately she decided to stick to reading writers of colour.

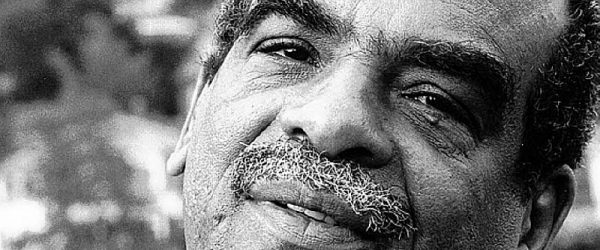

She found Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to be a ‘revelation’ because it presented complex, multidimensional characters of colour, like herself, rather than conspicuous caricatures.

In January 2016, writer Bani Amor started the online reading group for people of colour, Everywhere All The Time.

The project focused on decolonising travel literature, a genre traditionally flooded by white perspectives. This initiative exposed the absence of people of colour in literary circles, and also kickstarted other book clubs, reading groups and reading rooms centred on non-white, non-Western experiences.

People sign up through Tiny Letter and Bani emails through the next book and the meeting time. The group meets once a month through video chat and talks about the book, travel literature and their hopes for the future of the genre.

In the past, the book club read Migritude by Shailja Patel, A Small Place by Jamaica Kincaid and Belonging: a Culture of Place by bell hooks.

Similarly, Shirin Shah began the Brown Girls Book Club and focused on identity and collective challenges faced by South Asians based in London. The group operates primarily on Facebook, but also has meet-ups in London. ‘I think books have an important role to play by opening our eyes to different experiences,’ Shirin says, ‘and thereby challenging our conditioning.’

Like me, Shirin mostly studied texts by white men at her school in the UK. She rarely encountered texts that featured protagonists of colour. Shirin’s initiative had a clear demand because tickets sold out at ‘the blink of an eye’.

As the group is online, those based outside of London can also participate, meeting likeminded South Asians and connecting to a global community. The group runs on a policy of inclusion for people who have long been excluded from the centre of literature.

‘We did not want anyone to feel excluded from the conversation and post thematic questions on our social media starting the weekend before the meet-up,’ says Shirin.

Online communities help bridge the educational and geographical distance; Cher believes that these communities help combat the isolation and alienation that many readers of colour feel.

Another obstacle can be the actual procurement of the book. As a teenager in Sri Lanka, I found it really difficult to source writers of colour, even those from South Asia. This meant I only read authors from ‘the English language canon’. The rise of online bookstores has certainly aided in this search.

Bobuq runs a reading group based in Melbourne called In(Visible), which is facilitated by people of colour for queer, transgender and intersex people of colour (QTIPOC). Ahead of the meeting, Bobuq uploads the shorter readings online so that those that are eager to read ahead can do so.

‘People can expose themselves to the language and read in advance,’ Bobuq notes. ‘This is a form of anxiety mitigation.’

Despite this approach, there is no prerequisite for reading in advance at In(Visible). The project provides printed copies or books available for attendees to use at the meet-up, ensuring that everyone who joins has some degree of exposure to the texts.

In(Visible) collaborated with blogger, Negro Speaks of Books, to read and unpack Ellen Van Neerven’s Heat and Light. Organisers also handed out an additional six copies of the book for free to those in attendance.

Negro Speaks of Books also runs The Noble Savage Bookclub, also based in Melbourne, which celebrates Black literature.

Alongside each Facebook event, the book club lists a series of places where the book can be found. This includes a search at the local Melbourne City library, bookstores (either Readings or Dymocks) or to order it online for the Book Depository.

For beginner readers, finding a book can be a source of anxiety. It is mostly research-based spaces like universities that teach people the methods to search for books and texts. As a result, a lot of people who did not study such subjects or even go to university can struggle with these skills.

It helps to have spaces that foster reading and provide the books themselves or list a series of methods to acquire the book – Negro Speak of Books does just this. The gap that once separated writers of colour from audiences of colour can be more easily bridged through increased accessibility to books.

While I constantly spoke up in my university classes and everyone listened, I never truly felt understood. Either the tutors or students did not care or did not understand the context that I rooted my contentions in. Similarly, Bobuq noticed hostility to students of colour in tutorials.

‘Multiple races attempted to cohabit space and this amounted to white people using quite domineering language to take up space.’ Bobuq observes ‘A small, skinny, white person can take up a whole room of space using language that is quite intimidatingly academic and verbose.’

Bobuq, Bani and Shirin centre the voices of their marginalised participants. Though the participants might not have access to theoretical discourse, they are guaranteed the chance to be included and, most importantly, be heard. Because of the lived experiences of oppression, the readings and discussions are more likely to resonate on an emotional level.

These spaces have also elevated representation on many planes – for example, representation in the book, the readers who join the group, the organisers of these spaces and the facilitators that run discussions. These are examples of inclusion and participation that previously did not exist.

In fact, as people see representations of themselves, they shift the conversations from the books to conversations about themselves and their communities.

‘We tend to use [these] stories as a vehicle to talk about our own, and usually end up veering away from the book and deeper into our own thoughts and experiences, tangents, and talk about other books.’ Bani says.

They go on:

The true purpose of the club is to foster dialogue and build community for travel writers and readers of color, to bring attention to the literary contributions of people of colour to the travel canon, and hopefully inspire more of us to write and disseminate our stories. It’s almost like it’s an excuse for us to gather and talk about these things, because there really aren’t that many other places for that.

I feel that unlike in university, where I had no control over the syllabus (which actually ignored experiences and stories like mine), the personalised element of studying literature is reinstated in book clubs, reading groups and reading rooms. These places become spaces to build communities from.

Perhaps, this is best illustrated by Torika Bolatagiti’s Community Reading Room (CRR), a reading room that had texts ‘for, by and about First Nations people’, and which placed First Nations people at the centre rather than at the margins of history.

‘The first presentation of the Community Reading Room was at Colour Box Studio on Nicholson Street in the heart of Footscray,’ recalls Torika. ‘One day a young musician came in and shared that he had never seen himself represented in a book collection like this, and that he had been attracted by the Bob Marley biography in the window. We sat and talked about how he might connect with other musicians in Melbourne.’

Torika’s story illustrates that the book (Bobuq calls the book ‘an anchor’) and discourse are foundations to build relationships from. These book clubs are spaces to meet likeminded people, build connections and explore emotions together – as a collective.

Bobuq recounts how Eve Sedgwick’s ‘You’re so Paranoid You Probably Think This Essay is About You’ put paranoia under a spotlight and enabled readers in the group to reconsider their emotions concerning HIV in the QTIPOC community.

‘People of colour are more represented [globally] in HIV than other populations. So it is important to talk about because it assembles our emotional and structural landscape on our communities,’ Bobuq said. ‘People do feel anxious as they talk about their histories and traumas. It does evoke and elicit those reactions. We really want to make space for that because that’s real.’

Perhaps one of the biggest concerns of spaces for readers of colour is that they could easily turn into echo chambers. In countering this argument, Shirin points to the level of diversity in South Asia.

She perceives her project as a ‘safe space’ for the diverse cultures of South Asia to group together to explore their collective ‘problems and issues’ before they are taken into larger society.

In many parts of society, diversity has not progressed beyond the token person of colour. The diversity inside ethnic communities should be further interrogated and understood. Racial tensions and biases inside our communities – inside all communities – have to be dismantled if white supremacist structures are to be toppled for greater equality, representation and autonomy.

If I had access to these kinds of reading spaces as a university student, I might have had a more enriched education that had more relevance to my life and to the historic and contemporary legacies of racism and colonialism.

But, let’s just say the ball has started rolling because people that had been in exclusively white spaces in the education system have quietly subverted those spaces.

‘Being able to claim that didactic narrative that you are being taught by postcolonial narrative through the lens of whiteness,’ observes Bobuq, ‘and then being able to see this and redirect it to your own purpose, through your own voice and through your own communities – yes, that’s an act of resistance, I believe.’

Ultimately, people of colour are controlling their stories, retelling their histories and distributing their experiences for the improvement of their communities. These are acts of self-determination and resistance, but as someone standing at the margins, I’d like to see more.

Image: crop from Brazilian version of Americanah.