The Capitalist and the Socialist are at each other’s throats, but the issue between them is, which can ensure the distribution of the most goods to the people? No statesman, no pacifist, no League-of-Nations enthusiast, would entertain his pet scheme for a moment longer if he believed it would mean that ten years later people would buy half of what they buy to-day.

Samuel Strauss, ‘Things Are in the Saddle’ (1924)

When I came of age politically, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, anti-consumerism and anti-corporatism formed an ethos on the left that felt coherent, energising, and consequential. At a time when the creep of business ontology into every aspect of our individual and collective lives still felt resistible, books such as Naomi Klein’s No Logo and movements like culture jamming and Buy Nothing Day seemed to both clarify and contest the contours of twenty-first-century consumer-capitalism.

I can recall following the McLibel case closely as a thirteen-year-old and hacking corporate logos out of my school backpack. My politics were substantially formed in that cauldron where the personal and the political met and dissolved, and I was naïve enough to believe an alternative was possible to Marx’s vision of a world in which everything, eventually, would be subsumed by commerce.

Under such conditions, the charge of ‘selling out’—as I understood it—was less to do with, say, the rock critic’s ideal of an ‘authentic’ and anti-establishment attitude than with material struggles: for fair labour conditions, a less polluted biosphere, and private and social spheres free from the spiritually corrosive effects of advertising.

In the classic Capitalist Realism, Mark Fisher described the titular concept as

the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.

For Fisher, the coordinates of contemporary socio-political life had been set in the 1980s by the crusading neoliberalism of Thatcherism and Reaganomics, and deviation from this course was not merely unviable but beyond imagining.

Fisher was explicit that capitalist realism could not be localised to, say, art or advertising—it inhered in the atmosphere of life itself—but it seems to me that our sense of consumer-capitalism’s inevitability is a vivid illustration, if not distillation, of his idea. We might even think of it as consumerist realism, the feeling that the pervasiveness of consumer culture—in which the ‘slow unleashing of the acquisitive instincts’ which began in the eighteenth century has quickened into the sense that to consume beyond mere subsistence has become our principal role in the world—is not only irresistible, but rigidly enforced.

The left’s resignation to this state of affairs became ever clearer as I entered my twenties and thirties. I remember hearing a fellow progressive unironically describe McDonald’s restaurants—once the epitome of everything that seemed wrong with consumer-capitalism, from exploitative and unsafe working conditions to propagandistic advertising and animal cruelty—as ‘safe spaces’ because they were open 24/7 and sold cheap food.

I remember, too, hearing about a gathering of inner-north Melbourne artists at which conspicuously branded clothing and footwear was worn as a pointed rejection of anti-consumerism. Perhaps this was an outlying case—a hipster’s joke within a joke—but for me it would come to signal the beginning of anti-consumerism’s decadent phase, and the capture of swathes of the post-millennial left by a form of identity politics in which clothing took on a new semiological heft, much of it ironic. I think it’s also true that the kind of anti-corporatism championed by Klein in the 90s has to a large degree mutated into the paranoid conspiracism that is a defining feature of today’s political landscape (something Klein touches on in her latest book, Doppelganger).

The refusal to ‘sell out’ may have guaranteed a lifetime of ‘impotent marginality’—to use a term of Fisher’s—but at least it acknowledged that something real was at stake, the unambiguous articulation of which really mattered. At a time when the climate emergency ought to have supercharged our antipathy towards overconsumption, it has instead been headed off by so-called ‘conscious consumerism’, a movement predicated not on buying less but buying differently.

In theory, this entails consumers taking into consideration the whole of the production and supply chain, and making choices informed by the social, ecological, and political impact of the products one buys. In practice, many ‘ethical’ products are made by the same companies as their more obviously harmful counterparts, functioning as a form of greenwashing for which consumers typically pay more. Our cynicism towards advertisers’ expressions of ‘intrinsic’ or what we might call feelgood values could not be higher. No doubt it has also been fuelled by the repeated failure of recycling schemes, which have traditionally placed the onus to ‘do the right thing’ on individual consumers rather than companies and regulators. Under consumerist realism, such scandals are becoming thoroughly normalised.

So, too, is the fact that an increasing number of mainstream movies, once merely backed by multi-million-dollar advertising campaigns, are coming to be ontologically indistinguishable from such campaigns themselves. As Martyn Pedler noted in a recent Overland essay, a scramble is on in Hollywood to alchemise existing IP into box office gold.

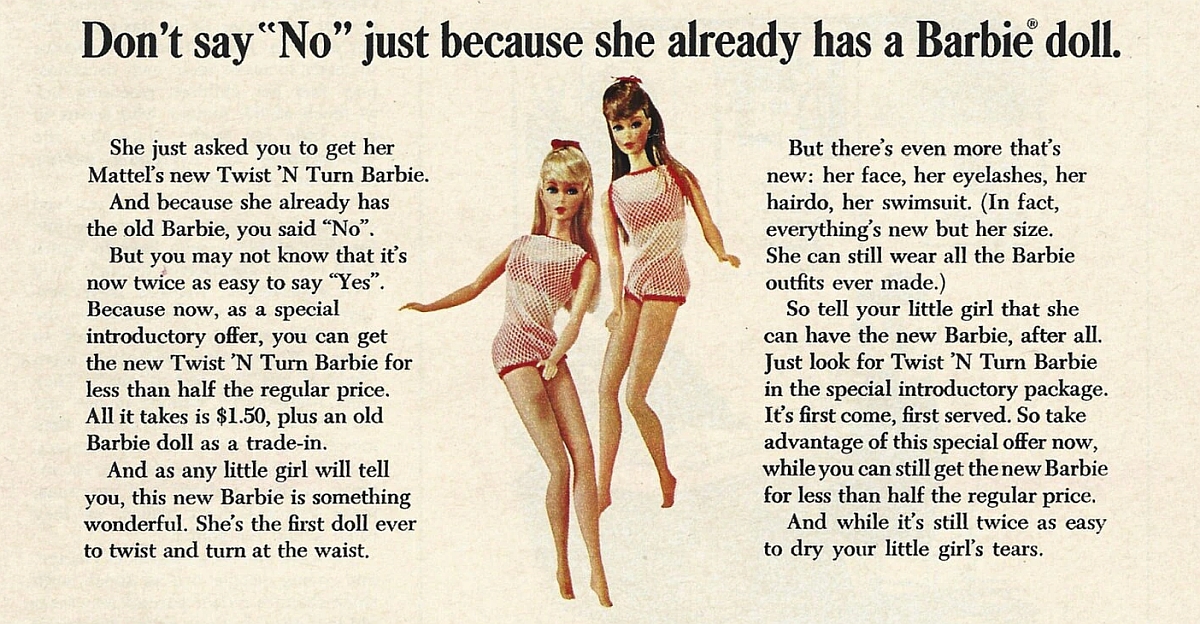

In the wake of the hugely successful Lego Movie in 2014, the Mattel toy company has made the even more successful Barbie—more on this shortly—and is planning movies based on Hot Wheels, He-Man, Polly Pocket, the View-Master, and the popular card game Uno (the latter in the form of a ‘live-action heist comedy’ no less), while competitor Hasbro is working on its own cinematic universe. We have already seen—or, equally likely, done our level best not to see—what can only be described as feature-length ads for Nike and Cheetos. As Pedler wrote,

the peculiar thing about these movies is that they weren’t paid for [by] their product placement: instead they make their profits by appealing to our interest in the products themselves.’

It is, of course, necessary for these companies to provide several spoonfuls of sugar to make the medicine go down, often in the form of appeals to nostalgia. As the Lego Movie’s animation supervisor Chris McKay put it:

We took something you could claim is the most cynical cash grab in cinematic history, basically a 90-minute Lego commercial, and turned it into a celebration of creativity, fun and invention, in the spirit of just having a good time and how ridiculous it can look when you make things up.

Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach’s Barbie relies even less on directly appealing to children, as evidenced by the transparent boredom of the kids who had been dragged along by their thirty- and forty-something parents to the Sunday afternoon screening I went to. Rather, it is framed as a nostalgia trip, albeit one as riven with contradiction as every other aspect of the movie.

If Barbie is intended to evoke the warm and fuzzy childhood memories of adult audiences—and I think it is—then on one level, it’s strange that the movie seems so uninterested in how children have historically played and interacted with the titular toy (we are shown a montage of old-school home movies, apparently sourced from members of the cast and crew, but it’s hard to know what we’re supposed to make of it beyond a certain wistfulness).

In the movie’s matriarchal utopia Barbieland there exists the character of Weird Barbie, a representation of the dolls which have been played with ‘too hard’ by children in the real world (faces drawn on, hair burned and hacked off etc.)—here rendered an archetypal mentor figure rather than something like the scary ‘mutant toys’ of the first Toy Story movie.

But whereas The Lego Movie and the Toy Story franchise appeared concerned with the question of their toys’ relationality, in Barbie the doll is almost all symbol, a floating signifier onto which filmmaker and audience alike can project whatever meanings they want. As the Marxist writer and blogger Richard Seymour observed of Toy Story 3:

There’s … a calculated element of Rorschach, wherein elements and motifs from history and ideology are scavenged and re-deployed, so that you can retrospectively read into the movie—whose effects you have just involuntarily responded to at a basic physical level—whatever rationalisation for so responding that makes you good with it.

This multivalence isn’t a bug but a feature of Barbie, something the movie’s tagline makes explicit: ‘If you love Barbie. If you hate Barbie. This movie is for you.’ Nobody, least of all the movie-going public, is let off the hook. This is consumerist realism laid bare.

Replace the word ‘Barbie’ with ‘feminism’ and the movie’s tagline makes just as much sense. Writing in the conservative Canadian broadsheet the National Post, Jamie Sarkonak argued that Barbie is

an enjoyable watch for anyone: ultra-feminists will like the literal interpretation of the movie that tells the viewer that the feminist utopia is good; and those more critical of feminism will enjoy how the movie shows the viewer that utopia isn’t actually all that great.

This view—that Barbie can be read as either feminist critique of male power or cautionary tale about capitalism’s wokeification and the inversion of patriarchal gender inequality—is perhaps just another way of saying what Gerwig has herself said: that in making the movie she wanted to make, she was both ‘doing the thing and subverting the thing.’ Doubtless Mattel and Warner Brothers, however squeamish they may have been initially with Gerwig’s irreverence, are delighted with the outcome: a movie that can be everything to everyone—a unicorn in these fragmented, ‘post-Covid’ times in which even apparent safe bets like The Flash or the latest Indiana Jones can tank—and which has gone on to gross over a billion dollars globally.

Rather than acting as a means of exposing hypocrisy, Barbie’s knowingness starts to resemble a carapace, shielding the movie from any and all possible critiques. It’s the very definition of a critic-proof movie (most have heaped praise on it) in that Gerwig and Baumbach have ironised away every possible objection in real-time. Characters mouth platitudes about ‘sexualised capitalism’ and accuse Barbie of ‘killing the planet with [her] glorification of rampant consumerism.’ Helen Mirren’s narrator steps in when an apparent contradiction—Barbie, as played by the conventionally beautiful Margot Robbie, complains of not being ‘pretty anymore’—requires effacement via a wincingly self-aware joke about Robbie’s casting. I’m reminded of David Foster Wallace’s borrowed quip that irony is the song of the prisoner who’s come to love their cage.

In his essay on Barbie, Nathan J Robinson compared the limits of the movie’s critique to those imposed by Donald Trump on his Comedy Central roast: make as much fun of me as you want (including about my hair), but you cannot suggest I lie about how rich I am. In other words, the comedians could do anything but the one thing which would have given their jokes a genuinely transgressive edge: hurt the Trump brand.

Barbie literally gets called fascist by one of the movie’s most sympathetic characters, and the toy’s parent company is openly mocked for its historically male-dominated boards. Everything is permissible bar a commitment to the politics of anti-consumerism that goes beyond lip-service.

But even this criticism—that Gerwig could simply have inserted a stronger anti-consumerist sentiment into her movie—seems redundant before it can be made. The medium, not the message, is the message. What all the pink and Jacques Demy-influenced exuberance can’t disguise is what Gerwig knows all too well and is ultimately what makes Barbie such a cynical project. Michael Friedrich might have just as easily been speaking of Barbie as Las Vegas’s Punk Rock Museum when he wrote that

commercial culture has become our dominant means of imagining and describing dissent, and so much of our rebellious energy has been displaced onto nostalgic purchases.

Robbie’s Barbie is ultimately redeemed not by her rebelliousness but her assimilation in the ‘real’ world into white, bourgeois feminism. As Robinson noted, to accuse a film like Barbie of lacking an economic analysis serves only to reinforce the worst cliches of leftist cultural criticism. But, frankly, to hail it as a transgressive triumph as many critics have done seems to me to be just as risible.

As intended, Barbie hasn’t only been a box office success. Like The Lego Movie, it has also led to the revitalisation of a brand once assumed to be in terminal decline, with sales of the doll reported to be up 200 per cent since the movie’s release. It remains to be seen whether Mattel has misread the public’s appetite for ‘90-minute commercials’ but it’s clear that Barbie represents a new front in consumerist realism—one tied, despite a recycling scheme, to a product with a considerable environmental footprint.

Well, the consumerist realist might sigh, at least if there’s going to be a Barbie movie, it may as well be a joyful exercise in indie-minded nostalgia with a memorable production design. Perhaps. But such exhausted absolution surely begs the question: why does there have to be a Barbie movie at all?

A 2011 report for the Public Interest Research Centre on the cultural impact of commercial messages argued:

The public debate about advertising — such as it exists — has… been curiously unfocused and sporadic. Civil society organisations have almost always used the products advertised as their point of departure — attacking the advertising of a harmful product like tobacco, or alcohol, for instance — rather than developing a deeper critical appraisal of advertising in the round.

Gerwig’s film may, in part, ask us to consider the values of Barbie as a toy, but the very fact it is permitted to call them into question—is Barbie a tool of female empowerment or disempowerment?—tells us everything we need to know about its limitations as a political project. It is the cage, not the song, that demands a revolution.

Image: Flickr