As a scholar and teacher in criminology within the University of Melbourne School of Social and Political Sciences, my teaching concerns the nature of harm and violence. This work takes place on stolen Indigenous lands. At the school we do acknowledgements to country. We teach students about the logics and manifestations of the settler colonial project. We draw on lived experiences in our classes to illuminate interrelated systems of oppression, to show the workings of the prison-industrial complex, to unveil the colonial project that is the criminal legal system.

We teach students about power, power dynamics, power abuse, about domination, conflicts and war. We teach about oppression and state violence. We tell our students that power is also about resistance. We teach them to engage critically with texts, policies and laws.

We do all these things at a neoliberal institution that operates according to market logics and business interests — an institution that itself is complicit in the settler colonial project. As the recently published Dhoombak Goobgoowana report clearly highlights, the University endorsed scientific practices and thinking — such as eugenics — that fuelled racism towards Indigenous peoples. We now have Murmuk Djerring, the University’s Indigenous Strategy 2023–2027 which offers, amongst other things, an apology:

Our purpose is to benefit society through the transformative impact of education and research. The University of Melbourne commits itself, in carrying out its mission of education and research, to actions to right the historical wrongs done to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of our nation. [emphasis added]

I highlight “historical wrongs”, as it seems to suggest that racism is a thing of the past. As if settler colonialism were a historical event. As if the University has now come to terms with its problematic history.

Framing the University’s mission of education and research as righting historical wrongs denies the ongoing violent and political relationship between Indigenous people and settler governance. It also denies the role of education and research in serving exploitative, racist and colonial agendas. There is nothing reconciliatory about this statement. It suggests that, by virtue of making an apology and by carrying out its mission of education and research, the University has “reconciled” the violence of the past with its present and so, presumably, with this acknowledgment of wrongdoing, may move on. However, these gestures are not innocent – they imply dispossession, the taking of Indigenous lands and colonial knowledge exchange. And this process is ongoing.

None of these gestures — such as Indigenous strategies, reconciliation plans, apologies or land acknowledgements — carry any meaning or depth, nor reflect a genuine commitment to truth-telling and justice, when we cannot speak about Palestine. When the University expects us to be “objective” and to be careful in how we express ourselves politically in the classroom. When, during the student protests and Gaza encampment, the concept of “safety” was turned against the protesters.

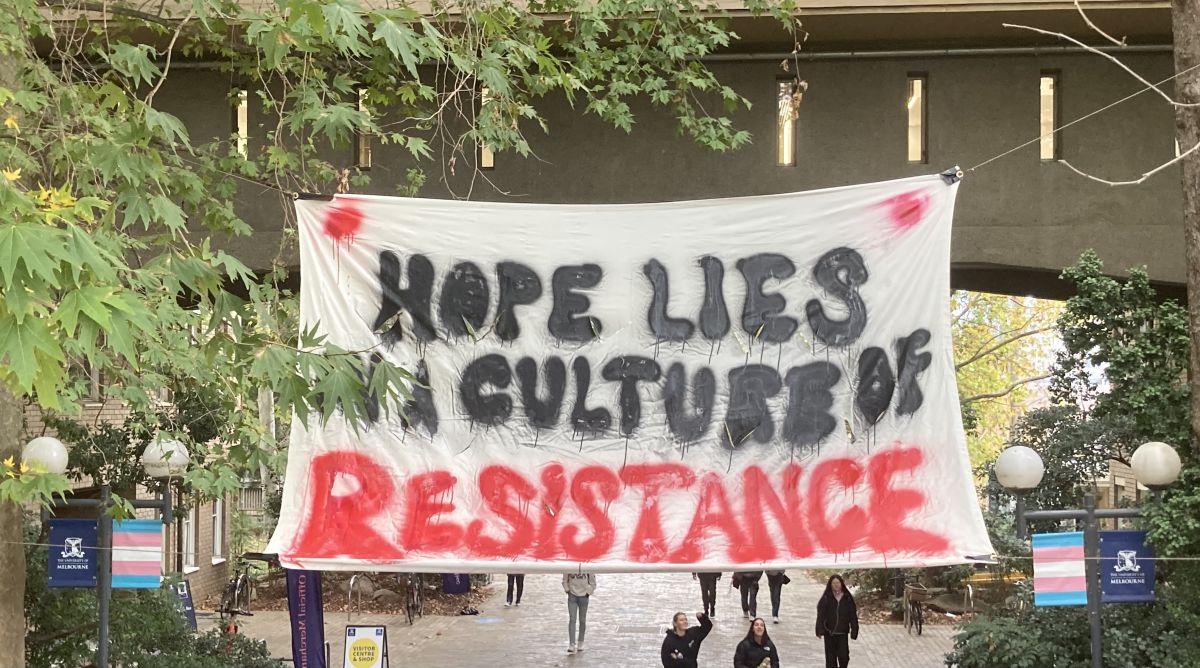

It was in the response to the protests that the University showed its true colors, and reminded us of its institutional power and its complicity in state violence. When your response to the Gaza encampment and student protests is the weaponisation of safety, the disciplining of staff and students involved. When your response to the protests is the threat of police intervention on stolen lands, while at the same time holding smoking ceremonies and doing acknowledgements to country, and while First Nations staff and students work on these lands — what does this tell you about the University’s reconciliation plans and its commitment to truth-telling and justice?

Mohawk scholar Audra Simpson says:

And in these times when the drive to death is apparent, … when Indigenous people are rising up all over, holding hands with settlers in absolute concern, grief and outrage, the language normatively should not be ‘reconciliation’ since the historical violence of colonialism is not over, it is ongoing.

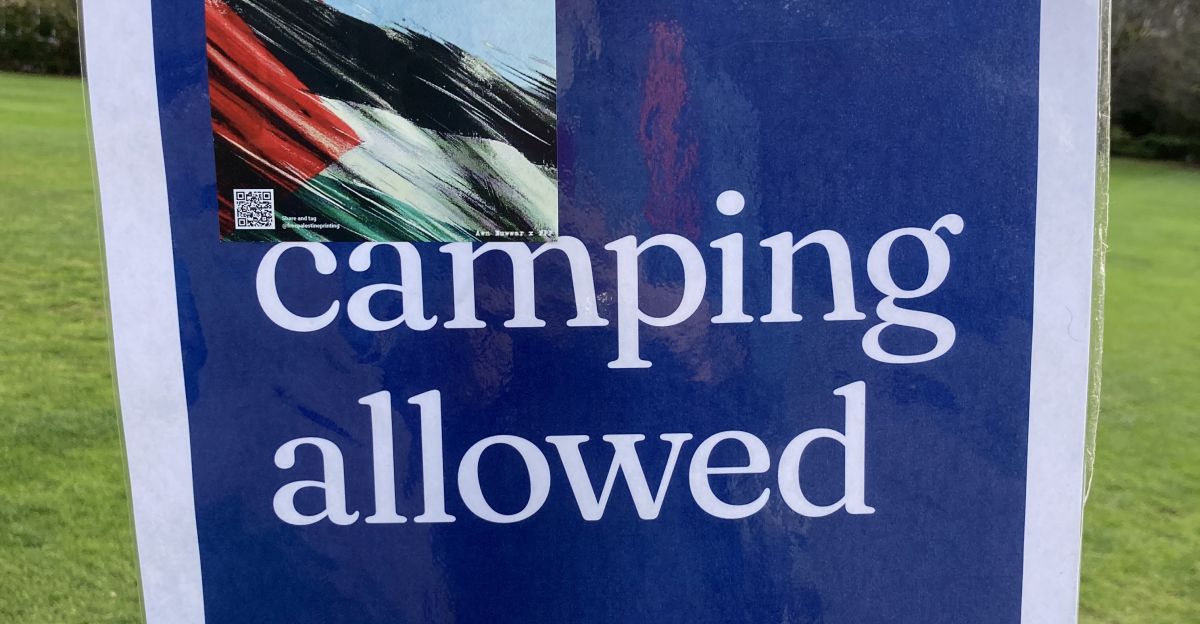

No camping allowed

The chilling effects of the University’s response are real and reverberate across our community, for both staff and students. Subtle reminders such as the “no camping” signs on South Lawn remind us of what the University will do if protests were to happen again. Placing these signs on stolen Indigenous lands tells us something about the actual nature of the University’s commitment to truth-telling. It further ignores that signage and fencing, as markers of private property, are hallmarks of settler colonialism.

The disciplining, erasing and silencing of anything related to the Gaza genocide was most evident when the University painted over a beautiful mural depicting Mahmoud Alnaouq, a Palestinian student who was about to start studying at the University when he was killed by an Israeli airstrike on 20 October 2023.

These signs, along with the University’s disciplinary responses, are being internalised by both staff and students. In time, we may come to experience these disciplining strategies as the norm. Academic freedom and critical thinking are threatened.

All of this clearly brings to light that there is no such thing as neutral education. Pedagogy that is about neutrality and objectivity not only kills the imagination but also kills critical thinking — an essential feature of academic learning.

So how do we keep teaching our students to think critically when the conversation around Palestine is policed and surveilled — when students want to speak about Palestine but teachers might be afraid to do so?

As teachers and scholars in this place, in this settler colony, it is essential we keep talking about Palestine and resolutely refuse the framework set upon us by the University. In the words of Micaela Sahhar, we must resist the fundamental presumption that teaching about Palestine is controversial. Or, as Leanne Betasamosake Simpson has pointed out:

In the context of resistance, generative refusal not only refuses colonialism, but it affirms a different present by generating different worlds — worlds that centre the material and spiritual needs of the community.

This is what we need to keep in mind when we teach. Refusal is not only possible, it generates different worlds. Refusal insists on the possibility of alternative anti-colonial futures and ways of being. Refusing the University’s erasure of Palestine involves a collective effort in thinking on how we will teach Palestine, the ongoing settler colonial violence and what this means for a place like Australia. And it means, as Amy McQuire reminds us, to see the government’s and institutions’ Indigenous policy and their complicity in genocide as “intrinsically linked.”

And if the University is really serious about reconciliation and righting “historical wrongs” it must unweaponise safety and provide infrastructural support for both staff and students to conduct discussions on settler colonialism and genocide “safely”, bearing in mind that, in the words of Sophie Rudolph,

the goal of ensuring safety … is a collective responsibility that involves continued critical engagement with the ways harmful systems such as colonialism and capitalism can be understood, reckoned with, and ultimately abolished.

This also means to resist institutional attempts at colonising the mind and to stand for epistemic freedom and justice.

All images by the author