The review by Christopher Allen for The Australian of Isaac Julien’s Once Again… (Statues Never Die) focuses on the work’s aesthetic and narrative choices. While this analysis reflects Allen’s established preference for certain formalist traditions, I want to delve further into the ongoing debate about how contemporary art can respond to the legacies of colonialism and its continued impact on cultural heritage. Julien’s exhibition, currently presented in the Macgregor Gallery at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art, offers a necessary provocation in the Australian context, where conversations about restitution and repatriation remain urgent and evolving. Once Again… (Statues Never Die) is not strident in its delivery but like good diplomacy the message still translates with precision and impact.

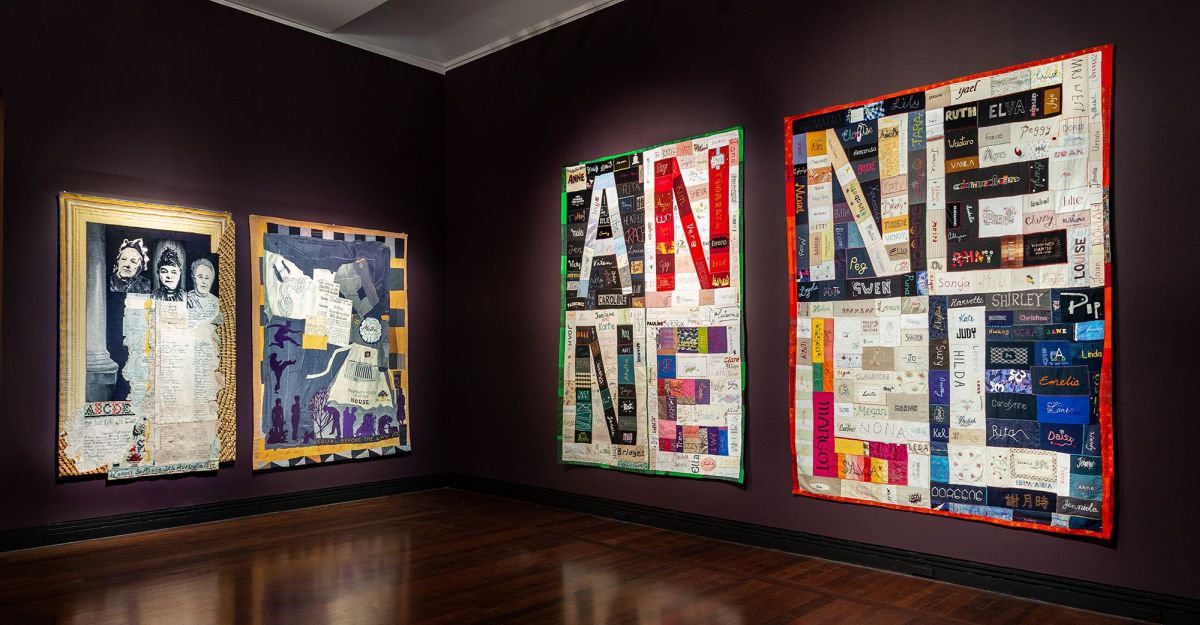

Julien’s five-screen cinematic installation, originally produced in 2022, is a powerful work of contemporary art, promoting dialogue about the restitution of Indigenous cultural objects that is highly relevant in an Australian context. The work explores the complex relationship between African art and the American artworld focusing on two pivotal figures — the late American collector Dr Albert C. Barnes and philosopher Alain Locke — whose influence is compellingly brought to life by the film’s actors.

The film is accompanied by a selection of nineteenth and early twentieth-century African objects, including several from the Australian Museum. This local context extends Julien’s examination of ownership and colonial legacies, and the global dialogue around restitution and Indigenous cultural heritage.

Julien, a Londoner, has previously exhibited this work at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, the Whitney Biennial in New York and London’s Tate Britain, as well as in the 15th Sharjah Biennial, Thinking Historically in the Present, conceived by the renowned Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor (1963-2019). Enwezor’s influence, shaped by postcolonial theory, resonates in Julien’s practice and aligns with Australian artists such as Brenda Croft (Gurindji/Malngin/Mudburra) and Brook Andrew (Wiradjuri) who also challenge Eurocentric narratives and examine questions of archival practice and the repatriation and restitution of cultural objects located in museums; as well as Tracey Moffat, who — like Julien — engages in exploring racial complexities in visual storytelling through cinematic and photographic mediums. Moffat’s 1997 Up in the Sky series is a strong example of her interrogation of colonial histories and displacement.

The exhibition of Once Again… (Statues Never Die) in Australia is important given the global momentum around restitution. This relevance is well illustrated by ongoing repatriation work being undertaken by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) under the Return of Cultural Heritage program. AIATSIS has identified 126,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural heritage items in overseas collecting institutions. Eighteen Australian Indigenous language groups have been involved in the return of their cultural heritage to date. Julien’s installation explores identity, collection, display and ownership of African art in Western museums, among other themes including gender and sexuality. It cleverly critiques the amassing of African artefacts in museums that has occurred largely during colonial expeditions and from looting. The artist captures how these objects have often been stripped of their proper cultural and spiritual context when displayed by Western institutions or become the subject of unacknowledged cultural appropriation by Western artists and modernism, or cultural fetishisation by collectors.

Julien highlights the tension between aesthetic appreciation of African and Indigenous art, and exploitation of Indigenous cultural heritage. The foregrounding of Alain Locke, an instigator of the Harlem Renaissance, prioritises an intellectual Indigenous voice, reversing the historical silencing of the cultures from where these objects originate. British colonial legacies are also present in the work. Unsurprisingly, the British Museum features, through inclusion of archival footage from Nii Kwate Owoo’s 1970 film You Hide Me.

Julien’s film explores profound themes implicitly, such as the moral complexities of museums retaining objects linked to colonial histories. The delivery is deceptively non-confrontational, gentle even, and is accompanied by soulful music by artists such as Alice Smith. The black-and-white imagery, consisting of archival footage and constructed scenes, is beautiful, elegant, even ornamental, at times homoerotic and frequently bathing the eyes with beauty. The viewer is gradually submerged into a place where greater understanding and reflection might occur, through hearing dialogue, such as illuminating speech between the collector Barnes and the philosopher Locke. In this conversation, Locke states: “This so-called primitive negro art… is really a classic expression of its kind entitled to be considered on par with all other expressions of plastic art.” And, “I did not connect makers of race with makers of art.”

The film is a masterpiece of editing and restraint: the deftness with which Julien selectively mines extensive archives in service of his work is an accomplished feat of reductionism. This is where his power, precision and mastery lie, in his ability to filter and communicate complex issues so fluidly, and with arresting visual clarity. The work is as powerful in its art form, aurally and visually, as it is in its socio-political messaging.

There is a genre of film-making developing around the subject of restitution; another example is the French Senegalese filmmaker, Mati Diop’s Dahomey (2024), a fantastical film about the return of cultural artefacts stolen by the French. It traces the actual repatriation of artworks from the Musée du Quai Branly to Cotonou (in Benin, once the Kingdom of Dahomey). Julien’s own artwork title is a reference from a 1953 film about looted art, Statues Also Die (Les statues meurent aussi), by Ghislaine Cloquet, Chris Marker and Alain Resnais.

Julien’s artwork is highly relevant to the postcolonial project broadly, and to advocating for the continued repatriation of Australian Indigenous peoples’ remains, and the restitution of their objects of cultural heritage which are dispersed across the globe. The film references works looted in the Benin Expedition of 1897, when British troops invaded the Kingdom. The ongoing global debates surrounding the British Museum’s retention of items such as the Parthenon Sculptures (the so-called Elgin Marbles) and the Benin Bronzes echo other challenges to those often faced by Indigenous communities. The British Museum has declined to return both the Parthenon Sculptures and the Benin Bronzes by appealing to the British Museum Act (1963). “Nothing is more galvanising than a sense of a cultural past,” is one line in Julien’s film. This echoes Nancy Alexander Rushohora’s claim that “repatriation serves as a catalyst for processes of public and civic mourning, without which people living in societies torn by crimes against humanity may be unable to heal.” Julien’s film implies this visually, poetically.

Once Again… (Statues Never Die) invites viewers to engage deeply, rewarding those willing to invest time contemplating its layered narratives. Transformative in its complexity, seductive in its visual literacy, it offers a space for empathy, education, and debate, emphasising how museums can serve as platforms for confronting contested histories and inspiring social change.

Isaac Julien: Once Again… (Statues Never Die) is on show at the MCA until 16 February.

Header image: Isaac Julien, Once Again… (Statues Never Die), 2022, installation view. Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, image courtesy Isaac Julien and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney © the artist, photograph: Henrik Kam