Textile and fibre art’s long association with the decorative and feminine — “women’s work” — has ensured the medium’s marginality in the history of the fine arts. In her classic study The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the making of the feminine (1984), Rozsika Parker traced embroidery’s status from a professionalised skill practiced by men and women during the Middle Ages to a leisure activity mostly enjoyed by affluent women in modern times. Yet, as Parker contended, women have also historically used these so-called “lesser arts” to convey subversive, albeit often secretive, messages in ways that have — to paraphrase art historian Ferren Gipson — transformed feminine art into feminist art.

Radical Textiles at the Art Gallery of South Australia recapitulates these ideas in an exhibition that presents works by around 150 artists, designers, and activists across the mediums of tapestry, embroidery, quilting, fashion, soft sculpture, photography, and video. In their opening weekend speeches, co-curators Leigh Robb and Rebecca Evans echoed Parker in their characterisation of textile art as “a trojan horse for the advancement of radical social and political agendas.” In her invocation of the “slow-making language of the loom,” Robb also referenced the unrushed, often collaborative warp and weft of fibre art that in itself presents a challenge to masculinist-capitalist ideals of unfettered individualism and productivity. As against this, the exhibition takes for its starting point the resistance of nineteenth-century British artist and designer William Morris to the mechanisation and mass production of the Industrial Revolution using the manual loom and hand-dyed thread.

In their catalogue essay, Robb and Evans also highlight an ethics of care:

… this project is as much about ‘care’, and its associated connotations, as it is about textiles used in radical ways in contemporary art. By their materiality, textiles offer a means for us to ‘care’ for ourselves, with fabrics used to provide comfort, warmth, protection and security, a sensorial connection augmented by a deep awareness of the personal, cultural, and collective memory with which they are infused.

The exhibition instantiates this ethos in a series of small, hand-stitched embroideries bearing slogans like “Stitch and resist”, “Black lives matter”, and “Voice, treaty, truth” — the products, one imagines, of the yarning circles, sewing bees, and “stitch and bitches” which — as Paul Yore notes in his catalogue essay — combine making and oral traditions and create spaces that are “feminine, circular, lateral, reciprocal and plural.”

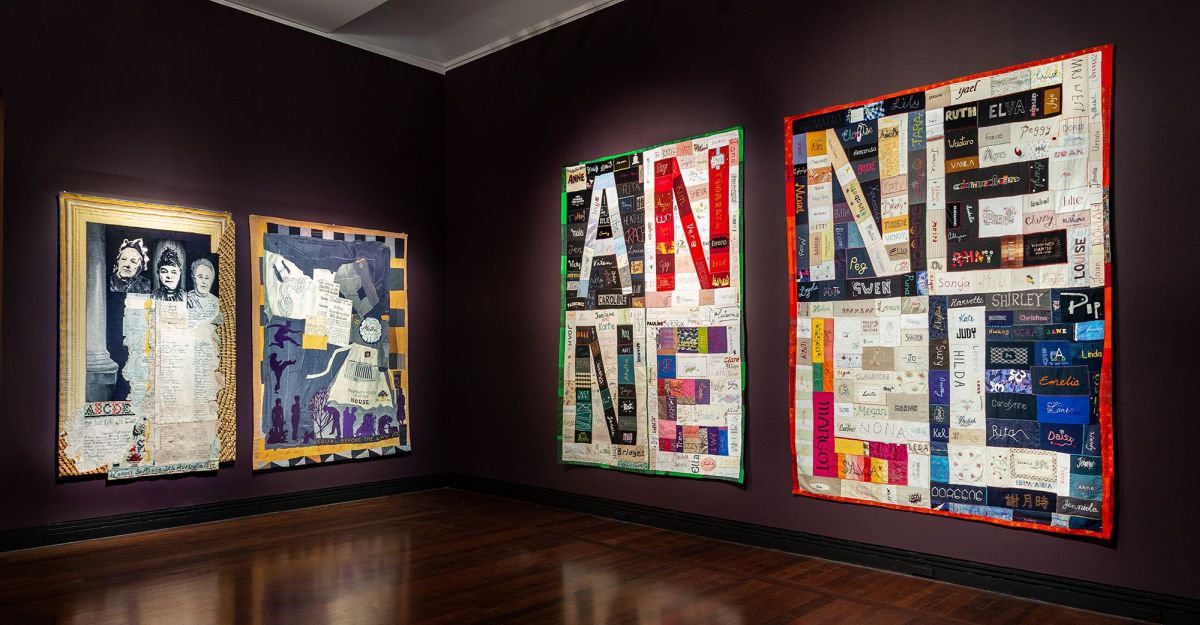

It can also be felt in the many large, communal quilts on display — vibrant, piecemeal assemblages of the discarded and forgotten repurposed as memorials to, and celebrations of, those marginalised by gender, disability, sexuality, and illness. Most striking of these are Nell’s NELL ANNE QUILT, which honours the memories of women significant in the lives of the 441 community members who contributed patches of fabric, and the South Australian AIDS Memorial Quilt, part of the global initiative launched in the late 1980s in San Francisco to memorialise the lives of queer men lost to HIV.

Yore’s quilt, Let us not die from habit, is, by contrast, anarchic and playful, described by the artist as “like a web that has been cast across the wasteland of culture, catching all kinds of flotsam and jetsam upon its surface.” I found works like these — massive, colourful, and semiotically dense — holding my attention for many minutes, their possibilities for meaning-making seemingly inexhaustible.

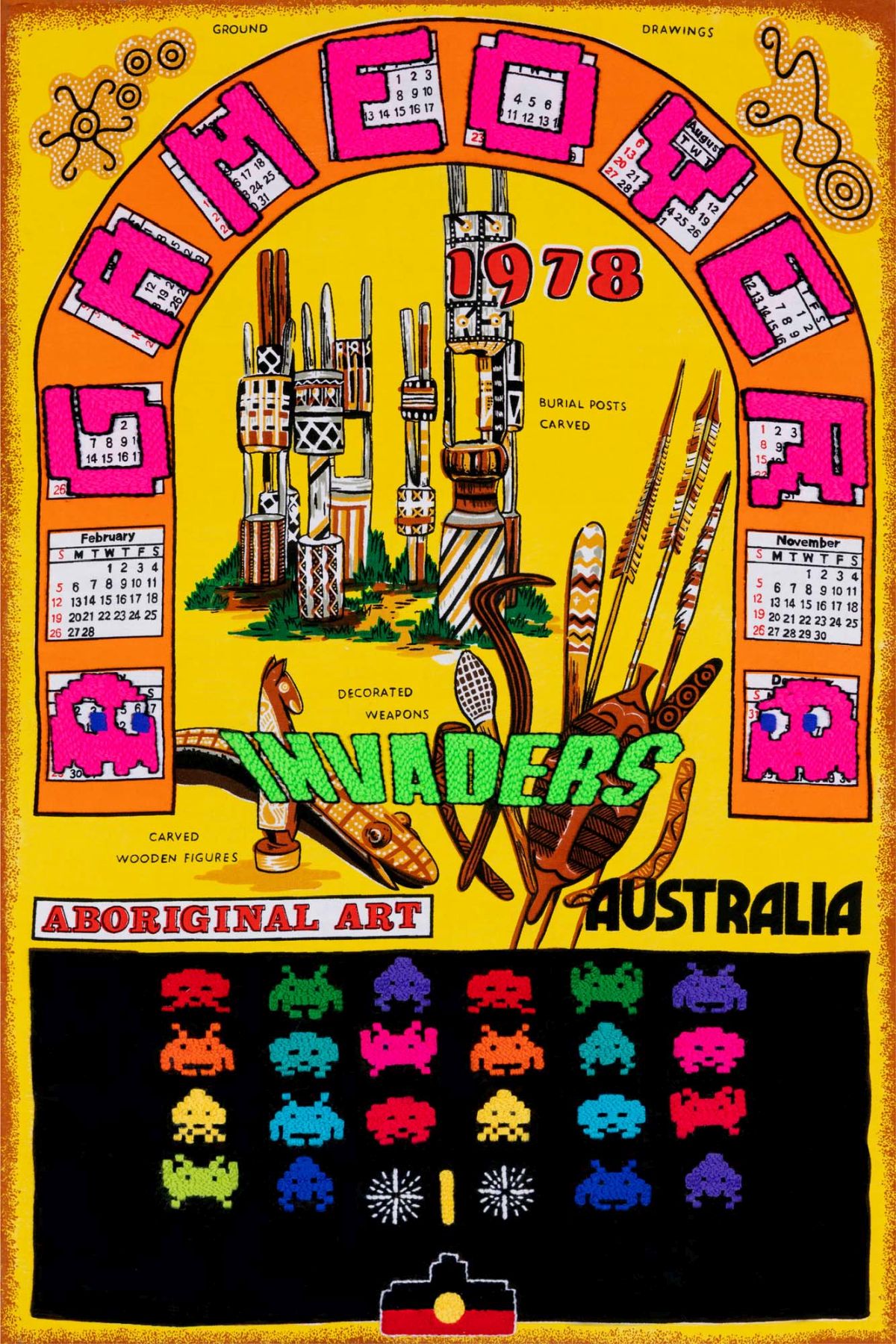

The Subversive Stitch has been repeatedly criticised for its Anglocentrism and failure to engage with rich, non-Western traditions of textile and fibre art. This bias is one that Robb and Evans are clearly at pains to avoid perpetuating, especially through Radical Textiles’ foregrounding of the work of First Nations artists and activists. As you descend the staircase to the galleries housing the exhibition, the first works you see are by Wadawurrung/Wathaurung artist Kait James — four reclaimed Aboriginal calendar tea towels from the 1970s and 80s. Using punch-needling, James has embroidered directly onto the tea towels, subverting their unthreatening kitsch with phrases like “Life’s pretty shitty without a Treaty,” “Lucky country”, and “Fu**er” (underneath an image of James Cook with a cigarette in his mouth and pink crosses covering his eyes).

Elsewhere, works large and small by Indigenous artists and collectives reflect the fruitful meeting of traditional and contemporary textile art practices, many reckoning with Australia’s imperial past in their reclaiming/repurposing of colonialist artefacts. A significant part of Radical Textiles is devoted to haute couture and wearable art, and it’s good to see a strong representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fashion — from Grace Lillian Lee’s black cotton dress of woven, tendril-like webbing, to Emily Kam Kngwarray’s Utopia-made batik print “Emily shirt”, to Clothing the Gap’s iconic Power Tee, emblazoned with the land rights rallying cry “Always was, always will be.” Also of note is the inclusion of textile art from south-east Asia and the Pacific, including a wonderful series of machine-embroidered panels by Eko Nugroho which deploy comic book-style illustration and politically charged sloganeering to critique the social inequalities of post-Suharto Indonesia.

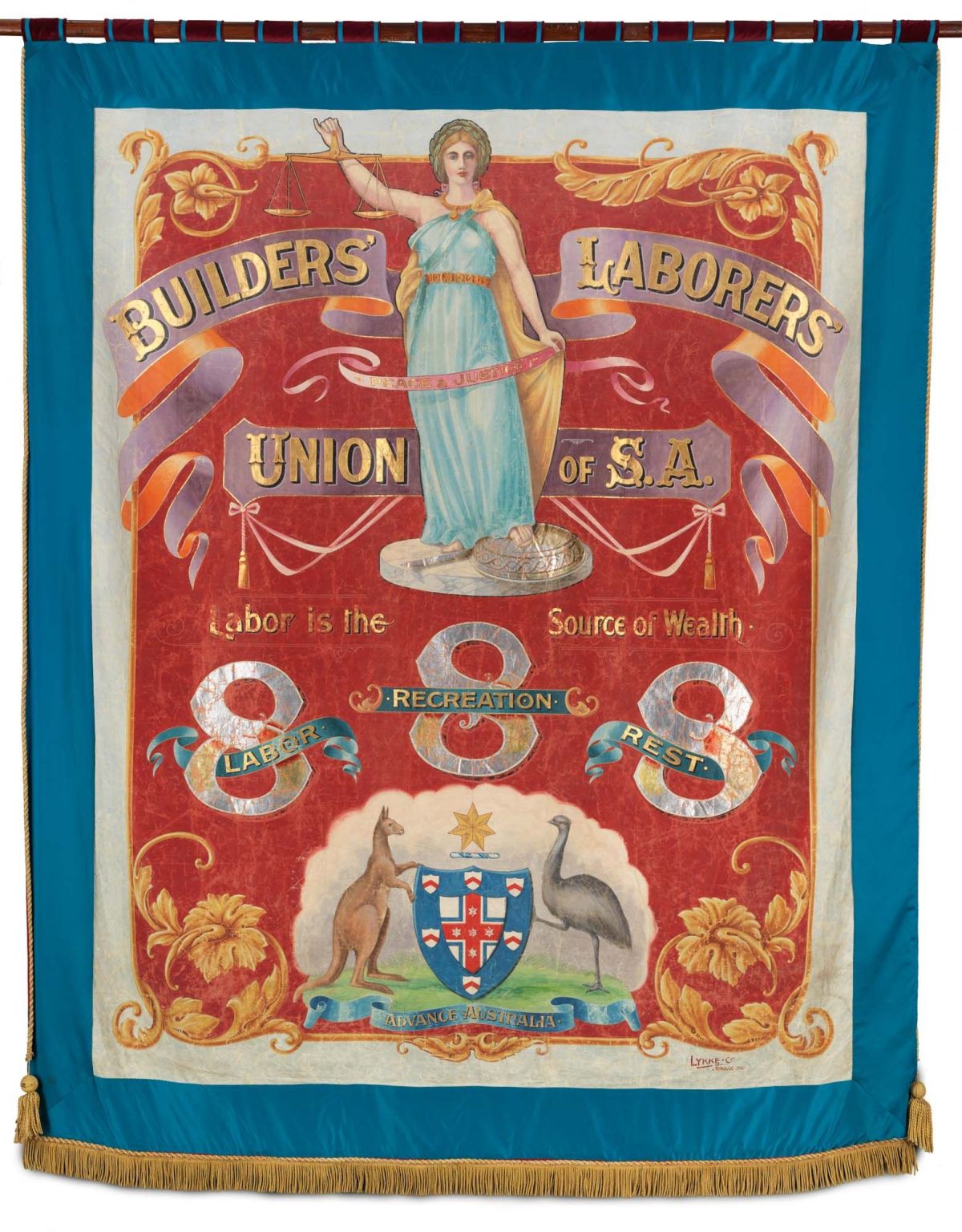

While showcasing such international and diasporic works, Radical Textiles also gestures strongly to the progressive history of South Australia’s parliament and trade unions. Prominently placed is a series of early twentieth-century trade union banners once proudly held aloft by members in May Day marches along Adelaide’s streets (and given amusingly tepid acknowledgement by state Labor MP Andrea Michaels on the exhibition’s opening weekend). One magnificent example by the Builders’ Laborer’s Union commemorates the winning of the right to the eight-hour day by Adelaide- and Port Adelaide-based metalworkers in 1873. Typically, the banner features the work of the union’s members in its depiction of the female figure of Peace and Justice and, in gold lettering on a background of red, the “three eights” — labor, recreation, and rest — and the motto “Labor is the source of wealth.”

Two tapestries, created by community weavers in the 1990s and normally hung facing each other in the South Australian Parliament’s Assembly Chamber, attest to the relative progressiveness of the state’s assembly in its enshrining of the principles of equality before the law and women’s right to vote — the latter won by suffragists in 1894 in a near-world first. Inevitably, Radical Textiles also includes Don Dunstan’s famous above-the-knee pink shorts, worn to Parliament House by the bisexual Labor premier in 1972, and which are framed as a blow struck for LGBTQI+ visibility in a city then notorious for its social conservatism and homophobia (three years later, SA would become the first Australian jurisdiction to decriminalise homosexuality).

*

Four years in development, Radical Textiles is an exhibition of impressive breadth. Its design, by Grieve Gillett Architects, is bold but uncluttered, and gestures to radical movements of the past in its use of colour — most notably various shades of socialistic red and suffragist/feminist purple. What strikes you as you wander through the galleries is not only the overtly political messaging of many of the works on display, but also the way that textile and fabric art makes visible the slow, quietly defiant labour of its creation, and gives form to the idea of solidarity across individuals and groups as a kind of weaving together. I found myself thinking, too, of not only the sense of care invoked by the curators in their opening speeches, but also of the violence inherent in needlecraft: the puncturing, pulling, and braiding together of sometimes disparate elements to force the new from the old.

An obvious question, then, arises: what is the meaning of “radical” art in the context of an exhibition presented by an historically colonialist institution that continues to maintain ties with BHP*, one of Australia’s largest-emitting companies with a track record of undermining efforts to limit global heating? The cynic might answer that in 2024 all art is always already compromised, thoroughly co-opted even prior to its existence by our late-capitalist paradigms of domination and despoliation. That’s as may be, but I couldn’t help but wonder if a radical retrospective is not something of a contradiction in terms, and if the battles for progressive reform sketched here are at risk of being transfigured into mere nostalgia. These struggles are, after all, rarely won for good, and some — like Israel’s ongoing occupation and decimation of Gaza and the West Bank, not referenced at all in the exhibition as far as I could tell — are a world away from just resolutions. Still, the truism that the present is impossible to understand without knowing the past applies here as well as anywhere, and in Radical Textiles may be found more than a few ideas worth stitching into — or assiduously disentangling from — our contemporary moment.

*The Australian mining company is the principal partner of Tarnanthi, a biennial festival of contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art presented by AGSA.

Header image from the installation, reproduced by permission.