Go to the ‘Memorial Redevelopment’ page on the website of the Australian War Memorial in Canberra and you will read this:

“Will they remember me in Australia?” a mortally wounded Australian asked Australia’s official First World War correspondent, Charles Bean during the bloody battle of Pozières in 1916. Bean later conceived of and resolved to build what is now the Australian War Memorial.

Since opening in 1941, the Australian War Memorial has recognised, honoured, and told the stories of our defence force personnel and their experiences in war and, later, on peacekeeping operations.

But Bean also said something else, which you won’t find on the AWM site: that the Memorial should ‘not be colossal in scale but rather a gem of its kind,’ the building ‘in the nature of a temple surrounded by a garden of its own.’ It’s doubtful that Bean would recognise today the building he helped found, much appreciate less the current plans for its expansion, which are nothing if not ‘colossal in scale.’ Announced by Prime Minister Scott Morrison in November last year, the $498 million redevelopment will see the extension of existing infrastructure, including the construction of a new entrance and the demolition and rebuilding of Anzac Hall, and the creation of a massive underground exhibition space. In a sign of things to come, an artist’s impression video on the AWM website shows visitors mingling in the presence of decommissioned Chinook helicopters and strike fighters.

The rationale for the redevelopment, which enjoys bipartisan support and follows the $600 million blowout of the First World War commemorations, is threefold: that new technologies are required to engagingly tell Australia’s war stories to rising numbers of visitors; that not enough of the Memorial’s vast collection is currently on display; and that existing exhibition space is inadequate to commemorate recent wars and peacekeeping operations in the Middle East and Asia-Pacific.

In reality, despite discredited official claims, visitor numbers are not increasing but have remained more or less constant for a quarter of a century. Meanwhile, as Paul Daley has pointed out, the ratio of the Memorial’s displays as a proportion of its total hard collection – four per cent – is normal or even above average for national cultural institutions. Most of said institutions – hit with ‘efficiencies’ equivalent to tens of millions of dollars in funding – can only dream of the resources the AWM commands with the barest of consultation or scrutiny. ‘Indeed,’ Daley wrote, ‘the trend in current museological practice emphasises digitisation, often ahead of bricks and mortar expansion, to democratise access to larger items and the things that are rarely displayed.’

Contrary to the claims by the prime minister and by AWM Director Brendan Nelson, the $498 million is not an investment in the telling of history so much as the bolstering of mythology. After all, what does the ostentatious display of planes and helicopters or the proposed live feed of current Australian Defence Force operations have to teach us about the past? Rather, their function is to project the Memorial into the sphere of public relations. This is a disturbing proposition, given the sponsorship of the Memorial by weapons manufacturers such as Boeing and Lockheed Martin and the Australian Government’s determination to become one of the world’s top ten arms exporters. Honest History’s David Stephens has described this relationship, in words that Brecht might have written, as ‘the military-industrial-commemorative complex: the arms maker provides, the ADF disposes, the Memorial commemorates, in a continuous cycle.’

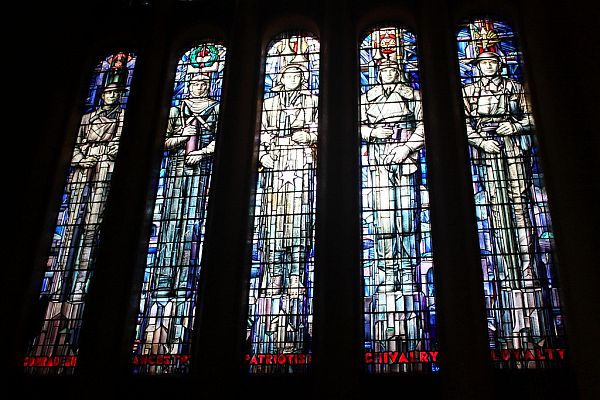

More fundamentally, the Memorial redevelopment completes the transformation of the Anzac myth from one earlier generations would have recognised –a muted, reflective phenomenon, for all its ahistoricism – into the triumphalist spectacle it has become today. Beginning around the time of the 1988 bicentenary, and supercharged by John Howard and every successive prime minister since, the resurgence of Anzac as Australia’s totalising creation myth was not inevitable but the result of a thorough, bipartisan campaign to place it at the centre of our national identity. But when so much of our actual history remains unreckoned with – from the Frontier Wars that the Australian War Memorial continues to refuse to acknowledge to the systemic maltreatment of First Nations people and asylum seekers, as well as the military blunders and wartime atrocities that official histories can still be relied upon to airbrush out – there is simply no justification for a boondoggle as large as this.

What else could the money be spent on? As is regularly pointed out, veteran support for one. But it could also fund a renaissance in the area of arts and culture (incidentally, this is where the AWM used to sit before Bob Hawke shifted it to the Veterans’ Affairs portfolio at the urging of mate and then-RSL President Sir William Keys). Arts organisations have called for the restoration of $25 million and $2 million per year to the Australia Council and Regional Arts Fund respectively. The $498 million being spent on the War Memorial expansion could reinstate these funds for nearly twenty years, revitalising an arts sector still reeling from the Brandis cuts of 2015-16. Equally, the money could be used to return, and even increase, the funds and jobs that have been stripped out of Australia’s other national institutions – the National Gallery, National Portrait Gallery, National Archives, and National Library – under successive federal governments, both Labor and Liberal.

If these institutions were really held to be equally important as custodians of our cultural memory, then why is the disparity between their funding and that of the Australian War Memorial so stark? How has it come to pass that, while the budgets and staffing of Australia’s other national institutions are whittled away year by year, Brendan Nelson can approvingly quote a man who told him that ‘whatever the government spends on the Australian War Memorial … will never be enough’?

It’s a mark of a fatal lack of imagination on the part of this country’s political establishment that a document as visionary as the Uluru Statement from the Heart can be dismissed out of hand while the Anzac myth is allowed to monopolise our sense of nationhood. The great Australian historian Inga Clendinnen wrote that ‘in human affairs, there is never a single narrative. There is always one counter-story, and usually several, and in a democracy you will probably get to hear them.’ In the increasing din of Anzac’s rehabilitation, Clendinnen’s use of ‘probably’ rings ominously. Untouched by irony, the right’s free-speech warriors in parliament and the press are evermore ready to howl down and drive out anyone who dares to dissent from the narrative.

There is, however, some cause for hope. A parliamentary inquiry into the future of Australia’s national institutions in Canberra has recommended the construction of a natural history museum and the relocation of an expanded Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies to the so-called ‘parliamentary triangle.’ But it remains to be seen whether other stories worth honouring – of Australia’s pioneering advances in the rights of women and workers, its precocious achievements in the fields of the arts and sciences, and, especially, the endurance of the world’s oldest continuous culture – will be heard, much less amplified to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars, in the years ahead.

See also: 100 years of Anzac: ludicrous spending for nationalist validation

Image: Stephen Mitchell