All night long I stood praying in front of an icon of Jesus Christ. Convinced that my organs were failing, I prayed continuously for days on end to absolve myself of sin and avoid damnation. I refused to eat or drink, in the belief that this would accelerate my decay. After six desperate calls to emergency services, pleading for an urgent liver transplant, my reprieve came. The sun had risen and it was a blaring, hot morning. Clutching the icon of Jesus, I was dragged out of the house and restrained to an ambulance stretcher. When I arrived at the emergency department I was in a wretched state. Dehydrated, emaciated and in a state of mental collapse, I continued praying. More than a religious effigy, the icon became my final point of refuge before the leap into abyss.

Years later, I started collecting the documents, artworks and objects connected to my madness. This has involved requesting copies of medical case notes, annotating drawings made in hospital, collecting used medication packets and reconstructing artefacts which were lost or destroyed. Key to this process was realising how objects and ‘things’ could be fundamentally transformed by trauma. Like similar objects preserved and exhibited in museums of war and remembrance, my icon became an artefact, or more appropriately, a psychotic artefact. Collecting these artefacts have forced me to confront the most painful aspects of my illness and integrate them into the story of who I am.

But there is more than therapeutic value to these activities. As psychotic illnesses remain stigmatised and ignored by the dominant mental health narrative, this work becomes a political imperative. As frightening as psychosis can be for both the sufferer and people around them, there is great creative and educational potential in their experiences. Through this process, both the ‘mad’ and their ‘madness’ start to make a lot more sense.

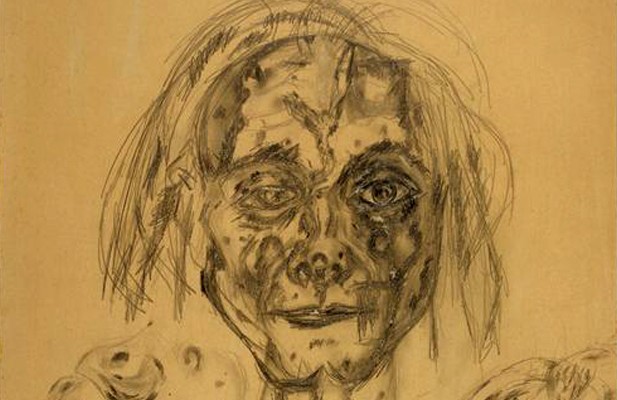

Archiving my psychotic experiences has been a powerful act of restitution and sense-making. For the mad have always been narrated by psychiatry; their creations collected, annotated and curated by institutions and by people who have never experienced madness themselves. It is time, in the words of French writer and artist Antonin Artaud, to pay attention to those ‘whom society did not want to hear’ and whom have long been prevented ‘from uttering certain intolerable truths.’ Welcome to the psychotic archive.

***

It is early October 2018, and I am checking into my Airbnb in the historic town of Heidelberg, Germany. I press the buzzer and am greeted with a short ‘hallo’ on the other end. I haul my luggage up the spiral stairwell and my host calls out from above. He takes a good look at me and says, ‘Just for a small trip? Jesus …’ I laugh. I enter the apartment and take in the musty cat odour. After showing me around, he confirms the reasons for my visit, ‘You here for the Prinzhorn collection, ja? That place with the art from all those crazy people?’ He tells me that a few years ago some ‘very disturbing pictures’ were shown at the Prinzhorn, which had to be taken down following a public outcry. My host didn’t see the exhibition, but remembers reading about it in the local paper.

I had indeed made the trip to visit one of the most significant collections of ‘crazy people art’ in the world. The collection bears the name of Hans Prinzhorn (1886–1933), an art historian and psychiatrist, who by 1921 had amassed over 5,000 artworks created by patients in German-speaking asylums. The Prinzhorn Collection is still housed on the grounds of the Psychiatric Clinic at the University of Heidelberg, along with a dedicated museum. Although works in the Prinzhorn can be labelled as ‘outsider art’, ‘psychopathological art’ or, more crudely, as ‘art of the insane’, it is undeniable that the experience of psychosis is tied to most of the artists in the collection. Prinzhorn himself states in the foreword to his 1922 book Artistry of the Mentally Ill that ‘the majority of the pictures (about 75 percent) originate with patients who are schizophrenics.’

One such ‘artist’ that brought me to the Prinzhorn was a dressmaker by the name of Hedwig Wilms. From her case file we learn that at the age of 38 she was admitted to a hospital in Berlin when she started to hear voices and suffer from fainting spells. She was summarily diagnosed with ‘menstrual psychosis’ and was temporarily released into the care of her family. Further admissions would have her condition described in now-defunct diagnostic terms like ‘hysterical mental disorder’ and ‘dementia praecox’. Wilms’ case notes document the terrible distress she experienced while in confinement. She drummed against doors and windows, hid under her bed covers, refused to eat, tore her shirt and had to be carried out of the hall while ‘screaming in the highest tones’. Remarkably, amid this chaos, she began to create.

On 10 April 1913, the case notes describe Wilms as ‘squatting on the floor, rubbing threads from slippers and laying them among the same figures … carefully next to each other, sitting with an air of majesty, refusing any interference with her work, giving only brief yes/no responses.’ By the time she was admitted to the Berlin-Buch Psychiatric Hospital in July of that year, her condition had deteriorated. She was put on a meal plan and had to be force-fed with a nasogastric tube. Her weight data was recorded every two weeks in the margins of her case file. As I traced these figures down the list I paused at the final entry: 29kgs. Ten days later on the morning of 10 August 1915 Wilms collapsed and never regained consciousness.

Today, Wilms’ legacy rests in a sole surviving work that was donated to the Prinzhorn after her death. It consists of a serving tray with a jug and coffee pot crocheted from cotton yarn. Viewed from an art-historical perspective, Wilms’ piece is a clear precedent for the soft sculptures of feminist artists like Méret Oppenheim and Yayoi Kusama. But how appropriate is it to view Wilms’ piece in this way without acknowledging the circumstances of its creation? Is her work more of an ‘artefact’, tied to the historical conditions of the asylum and the lives of those within them, than a formal work of art?

In the context of my psychotic archive, I argue that it is the ‘artefact’ that takes precedence over the ‘art object’. However, it is important not to ignore the value in presenting these works in spaces traditionally reserved for the ‘fine arts’. Using the logic of conceptual art, a movement that emerged in the 1960s, the archive itself can be transformed into an artwork. With this approach, psychotic artefacts become ready-mades, Fluxus event-scores are created from behaviours documented in case files, and psychotic episodes are re-enacted as durational performance works. As radical as these creative experiments may be, the didactic potential of the psychotic archive should not be forgotten. Above all, it is a way of talking about an illness which is so shrouded in fear and mis-understanding. This is a conversation without end and one that must continue, psychotic archive or not.

Lead image: crop from Antonin Artaud, Autoportrait 11 mai (1946)