Moved by Eaten Fish’s visual portrayals of life on Manus Island Processing Centre, an island location turned prison through the encroachment and domination of Australian law, I was triggered to think about whether cartoon art constitutes evidence of state violence. Since I began to write this piece many more documents have emerged by way of the ‘Nauru files’ also testifying to state-enabled practices of extreme violence triggering the bigger question: how much needs to be known before the practices stop? How does the Australian law, author of now well-documented violence, respond to allegations of this violence? Does evidence even have weight when it comes to state-produced trauma?

But first, the story of Eaten Fish.

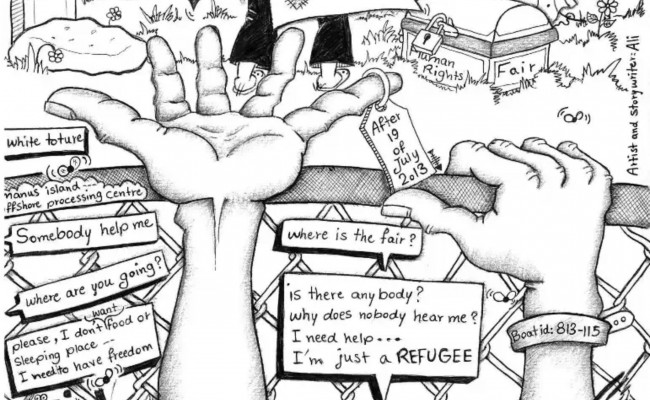

Eaten Fish is the pen name of 25-year-old Iranian Ali, who has been imprisoned on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea for three years. He documents the conditions of his incarceration through intricate artworks that tell the story of a place created by Australian law, surveilled by Australian law and yet full of trauma, abuse and violence. One drawing shows a sad young man, no doubt an autobiographical depiction, crying and holding up a sign saying ‘no means no’. In another image, the same young man imagines whether he is being approached by another man in the camp for friendship or for sex; in the dense image, there are many other men lurking in the background.

Eaten Fish draws imminent harm: his artwork exposes for all who care to look the violence that will occur in conditions of detainment and secrecy. In doing this, his art also historicises the camp by, for example, embedding into his drawings the headstones of those who have already suffered harm to the point of death.

‘Reza’ reads one headstone, the name of a 23-year-old Iranian asylum seeker who was killed during riots in the same place on 17 February 2014. On another headstone is written ‘Omid’, the name of an Iranian refugee who died after setting himself on fire and who remained untreated for hours at the Nauru detention centre.

Eaten Fish references stories that we know, stories that have been reported on, documented and investigated. And yet the violence has not ceased. In fact, Eaten Fish is subjected to ‘further violence’ as he continues to document the ‘unspeakable abuses and excesses of the guards and administrators of the camp’.

In announcing Eaten Fish as the recipient of the award for Courage in Editorial Cartooning, Joel Pett, president of Cartoon Rights Network International (CRNI), said: ‘his work pushes through the veil of secrecy and silence and layers of fences in a way that only a talented artist speaking from the inside can’. Robert Russell, also from CRNI, said ‘his cartoons will someday be recognized as important, world-class chronicles of the worst human behaviour since the World War II concentration camps’.

Unlike those reporting on the same violence from the outside, there is a high price to be paid by artists like Eaten Fish who is subjected to ‘further violence’ as he continues to document the ‘unspeakable abuses and excesses of the guards and administrators of the camp’.

A further body of testimony has emerged tracking the untold excesses of Australia’s refugee detention regime. Researchers against Pacific Offshore Black Sites (RAPBS) is a group actively campaigning to expose the violence resulting from the neocolonial Australian state practice of ‘offshoring’ duties to protect those seeking protection from the Australian state. The group has a website dedicated to highlighting practices of state violence and to give space to the voices of those who are trapped behind the barbed wire of the prisons of the Pacific.

Eaten Fish is one of the people whose plight is foregrounded on the website. Two of the founders of RAPBS, Suvendrini Perera and Joseph Pugliese, write of the deep significance of Eaten Fish’s drawings:

[A] prisoner is compelled to use the device of the ‘cartoon’, a seemingly benign and unpretentious genre, as a means to bring to public attention the daily crimes that transpire in Manus camp – despite the fact that legally admissable evidence of these same crimes is available from the CCTV recordings.

This, Perera and Pugliese say, is a ‘nightmare world in plain sight’.

Also bringing this dark world into Australia’s line of vision are the leaked Nauru files, published by The Guardian in August. More than 2000 of the files are ‘incident reports’ compiled by staff working in detention centres whose job it is to care for the refugees in detention. While assaults, sexual abuse, child abuse and other cruelty are meticulously recorded, the Australian state does nothing.

The Guardian has said that the public deserves to know more about what is happening on offshore prisons, which cost Australian taxpayers $1.2 billion per year. The paper also hopes there will be ‘an end to the political impasse that has seen children in Australia’s care languish on Nauru for more than three years’.

But the state already knew of at least some of the violence it was perpetrating. According to a Parliamentary Committee report in 2014, the violent incident leading to the death of Reza Barati was ‘eminently foreseeable’ with the Australian government being held responsible through its ‘failure to properly process claims for refugee status’. Nicole Judge said in her testimony to the parliamentary committee that she thought she had ‘seen it all on Nauru’. In fact she had not:

Manus Island shocked me to my core. I saw sick and defeated men crammed behind fences and being denied their basic human rights, padlocked inside small areas in rooms often with no windows and being mistreated by those who were employed to care for their safety.

Will the considerable evidence that has come to light be sufficient to overthrow this harm-causing regime and its enabling laws? Perera and Pugliese in writing about Eaten Fish describe an ‘insular world cordoned off from the rule of law and the applicability of any protective regime of rights’. This is a ‘black site’ one that RAPBS describe as a camp on Australia’s ‘own former colonial territories of Manus Island, PNG, and Nauru’. RAPBS name these places as black sites ‘in order to highlight their structural connections with other extra-legal or illegal places of confinement, abuse and torture’. What emerges from this characterisation and requires further unpacking is the way that these ‘extrajudicial’ zones hidden from view are at once are places ‘cordoned off from law’ and yet constituted by it. Further, while the camps are, as Perera and Pugliese argue ‘characterised by secrecy and lack of accountability the terror occurring in those places is now well known.

It is not without significance (significance that I cannot fully unpack here) that the Papua and New Guinea Act was passed in Australia in 1949 and that the country is a constitutional monarchy with the Queen of England as the head of state. Independence from Australia was proclaimed in 1975 even though the Australian state is still showing signs of asserting imperial control over PNG. When the PNG government announced that it would close the camp on Manus Island after it was declared unconstitutional by the PNG Supreme Court, the Australian government was unmoved with Minister Dutton saying that ‘the court decision is of course binding on the PNG Government not on the Australian government’.

Earlier this year, the Australian High Court had ruled that offshore immigration detention is lawful. This is despite the case itself being another key component of the mounting evidence of the suffering that was/is being sanctioned by such a decision. With the two legal decisions in conflict it is the ‘refugees and asylum seekers that remain unfree’.

The evidence of state violence exists not only in the art and testimony of those resisting it but in the official documents of the system itself. The Australian High Court decision of February 2016 declaring offshore imprisonment lawful is a detailed and chilling archive of the harm resulting from the laws that this pronouncement of law re-sanctions.

The evidence is abundant – official and unofficial, textual and graphic. And yet the violence persists. Law and its inherent violence is firmly implicated in practices that demand evidence, as well as laws that allow evidence of violence to be overwritten.

Image: detail of Eaten Fish cartoon / Save Eaten Fish

Related articles

‘Australia, exceptional in its brutality’, Behrouz Boochani

‘Editorial’, Jacinda Woodhead (current issue)

‘What comes after #LetThemStay?’, Jordy Silverstein and Max Kaiser

‘Just next door: on refugees and the worsening conditions in onshore detention centres’, Chloe Papas