In mid-May, I received a Facebook invite to ‘Vessels to a Story’, an exhibition put on by RISE Refugees, the only organisation in Australia founded and run by refugees, asylum seekers and ex-detainees.

‘This exhibition is not a celebration of “multiculturalism”,’ the opening sentence read, ‘nor is it a celebration of Melbourne as a “melting pot” of cultures.’ The cover image was an installation featuring arms and legs caught mid-stride in a cement wall, absent the head, limbs poised as though the figure were running at top speed before being abruptly immobilised. No, this was not intended to be a feel-good showcase of migrant success in multicultural Australia.

The month-long exhibit, which finished at the end of June, captured the attention of Fairfax Media and Buzzfeed. Both articles focused on Van Thanh Rudd’s The Vast Ocean, and the fact that Van is the nephew of former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd. But the exhibition deserves some detailed reflection on the other artists and their works, which went largely unacknowledged in the media.

Held on the first floor of the Library at the Docks, curator Dominic Hong Duc Golding’s statement of purpose posted at the entrance read: ‘Often considered simply as “vessels to a story”, these artists seek to reclaim narratives about them and reflect on the more nuanced and complex aspects of “the refugee story”.’

The descriptions of the artwork on display did not identify the artists’ ethnic background, nationality or migration status. There was no mention of art schools attended, or previous exhibitions that had showcased their work. The bio omissions read as both plea and demand by the artists: we want to be treated not as exotic sob stories but as artists – artists unafraid to get political, but who also take their art-making seriously; artists who do good art on top of practising good politics.

Upon entering, the first work in view was Van Thanh Rudd’s sculpture The Vast Ocean. In it, the figure of a limp, faceless refugee child in a life vest appears to be crucified; the faces of Peter Dutton, Malcolm Turnbull and Bill Shorten hang around the body. The logo of Wilson Security, the private security company running offshore detention centres, sits above the inverted triangle of the immobile child. It reminded me, a secular Catholic, of the trial of Christ, innocent but victimised because of the threat his presence posed for politicians. Another reading might be that the Christian value of love for the neighbour, or of being a good Samaritan to strangers, was rendered limp, held hostage to political and capitalist priorities.

The next display featured curator Dominic Golding’s work. His ink and pastel sketches featured overlapping images of the enduring traumas left by the Vietnam War. There were many smiles in the illustrations, which appeared on the faces of skeletons, and of men and women bearing guns. The most striking of these illustrations was the figure of a man divided: one side of clad in military battle dress, rifle in hand; on the other, an eye patch, with no arm, and no leg beneath his left quad. Striking, too, was the installation beneath the sketches: a scrapbook of photographs of Dominic’s travels around Southeast Asia to connect with Vietnam War adoptees like himself. Despite having grown up in a loving and devoted white Australian family, the war obviously still had much unfinished business with Dominic and his fellow adoptees. Dominic’s investment in the history that made him was signified not just by his art, but by the cost of pursuing DNA testing to track down his birth parents, depicted visually by tiny jars and toothpicks that scrape skin cells from the mouth, that are then sent off to a North American lab for processing. The answers he seeks, like the war he was born into, trace back to America.

The next work was a chilling sight that felt both contemporary and timeless: makeshift sacks made of blankets suspended from the ceiling, appearing to have been put together in haste, to carry what would become the owners’ only possessions in the world, as they head out to who knows where in the world. In the installation by Aseel Tayah, simply titled Bukjeh (sacks), the light falling upon the sacks created black shadows against the white wall – a haunting visual effect highlighting the sense of urgency and emergency that drives people into exile. A sculpture featured a small wooden boat: brown pieces of burnt pecan scattered over what appeared to be seawater made for an abstract take on deaths at sea, illustrating how the media and politicians treat images of brown and black migrant and refugee deaths as essentially similar and interchangeable. Opposite a video installation played, in which a woman looked out onto the swelling ocean. Called Our Way to Heaven, it was an ironic juxtaposition of the majestic beauty of the surf with the desperation of having no other hope but a leaky boat and a prayer.

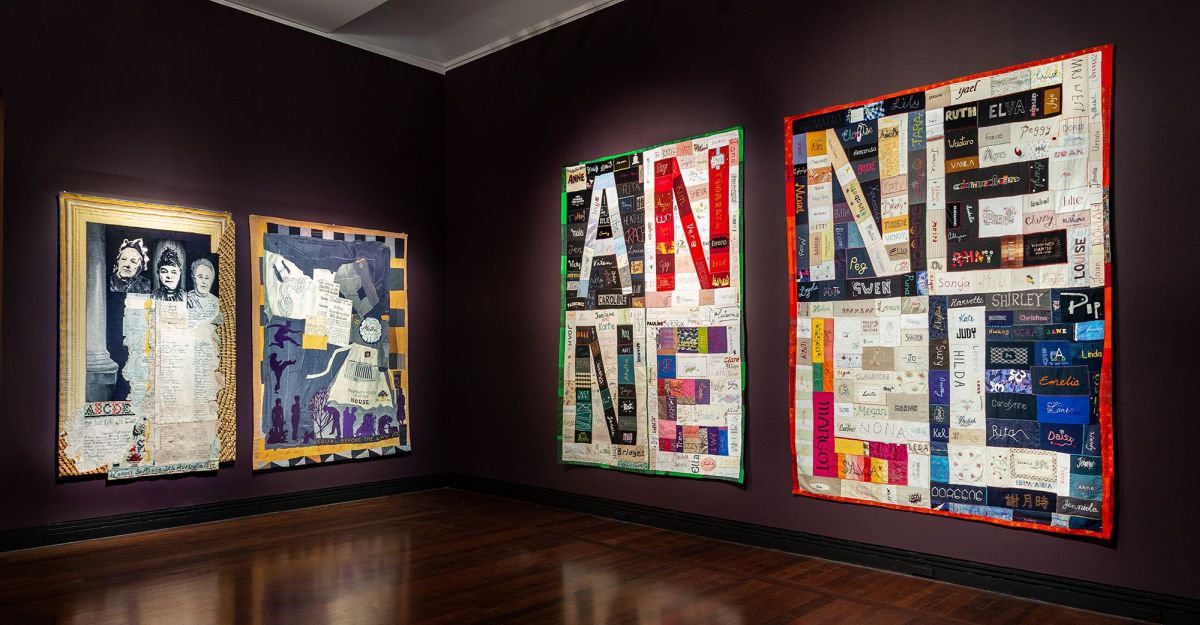

Placed beside this was an installation by Karen Schamberger, Unwelcome Wall, which invited spectators to think about the privileges of citizenship while being confronted with the fact that ‘Australia has one of the highest deportation rates in the world’. The figure includes the deportation of British-born unionist Tom Barker (returned to Chile in 1918), and the 238 people on SIEV 5 in 2001, ‘the first vessel to be turned back to Indonesia’. Projected onto the wall were the names, and sometimes, just the numbers, of individuals ejected from Australia due to various circumstances. ‘The Constitution contains no definition of Australian citizenship which could limit these powers and this enabled successive governments to apply them to an ever-increasing number of people,’ Karen explained in her notes. ‘Both mandatory detention and mandatory deportation became the primary instruments of immigration enforcement through the Migration Reform Act of 1992.’

The next corner showed work by Clarissa Yuki and Mohamed Nur. Their drawings emphasised the details of faces contorted in a myriad of emotions. For the most part, both artists had worked in black and white. Mohamed’s faces were those of men with downcast eyes; to me, they projected a sense of abject failure and trapped masculinity, and men unable to imagine a brighter future. Clarissa’s sketches, on the other hand, mostly depicted rage, in women and in men – upturned heads and hands in fists, suggesting a determination to express truth no matter what.

Another sketch, this one by an anonymous artist, showed the fate of refugees treated as a ball in a tennis match by government agencies such as ASIO and the private companies such as SERCO. A viewer in the scene comments, ‘Cases in Guantanamo were settled within two years.’

Tania Cañas’s piece came next: a brown mat stating ‘Unwelcome’. The design caught media attention in September 2015, when Tania laid out multiple mats in front of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection and Parliament House, as part of the Melbourne Fringe program. In the context of the RISE exhibition, the piece invited viewers to think about what true welcome means, and indeed who has the right to welcome newcomers to Australia. Another way of seeing it is was a literal doormat, a pushover, a signal that government departments are puppets to the whims of politicians and corporate interests that profit the most from the abuse of refugees.

The last display I viewed was devoted to Mahmoud Salameh’s work, the only artist with a detailed bio: ‘Palestinian-Syrian cartoonist, animation filmmaker, graphic artist, and ex-detainee.’ Mahmoud’s most compelling images were a sketch of a city skyline that looked like the middle finger, pointing back up at missiles merely feet from the building tops, and an image of a boy letting loose a paper plane into the heavens, only to find combat aircraft coming back at him from the sky. The images showed the relentless horror of armed conflict –when arms come from the sky, that place we usually turn our faces to see the sun or the stars. At the same time, the images were animated by a drive to spit back at the horror, with irreverence, with art, with a determination to try despite the odds. The bottom painting showed two boats, one suggesting refugees and the other suggesting Indigenous Australians, facing each other in the middle of the ocean, captioned ‘Which way?’ It harked back to the idea of who gets to say welcome, and whose land is being ‘encroached’, in the light of deeply embedded ideas about who gets to settle in Australia based on the circumstances of their arrival.

A common characteristic of all these works was the emphasis on the human face and figure. The amount of detail put into facial expressions and gestures told me that these artists want their images to be seen as images of human beings – unique, individual, even as they are subject to the same kinds of material conditions, those of people fleeing inhumane circumstances. The listing of the names in the Unwelcome Wall, the distinctly caricatured faces in the work of Clarissa Yuki, Mohamed Nur, and Dominic Golding, were a call for recognition of refugee people as people, thus deserving of respect and dignity.

The use of facelessness could also be observed in Van Rudd’s sculpture, Mahmoud Salameh’s paintings, and Karen Schamberger’s installation. I took this as a sharp riposte against movements seeking to create empathy for refugees through photos and articles featuring child refugees finding salvation through white humanitarianism, while obscuring the role of capitalism, politics, and the border regime in creating harmful and traumatic conditions for refugees and asylum seekers.

Exhibitions and displays such as Vessels to a Story encourage people to see refugee art not as an exotic testament to an unproblematic ‘multicultural Australia’, but rather as a way of making space and taking up space in spectators’ lines of sight. Through the thoughtful deployment of colour, line, light, gesture, detail and abstraction, the art in RISE’s ‘Vessels to a Story’ expanded the viewers’ horizons so that the plight of refugees can no longer stay unseen.

–