The national Closing the Gap policy contains targets to address what is described as Indigenous disadvantage. In relation to education these targets include intentions to improve English literacy and numeracy outcomes, school attendance, early childhood education participation and Year-12 completion rates. However, in the last ten years progress on these targets has been minimal and policy to address Indigenous education appears to be at a standstill. At the same time as the policy attention on Indigenous education has diminished, the rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people having contact with the criminal justice system has risen.

The Ngaga-dji Report offers an in-depth engagement with the challenges First Nations young people face when involved with the youth justice system. In this article, we have a conversation about what insights the Ngaga-dji report offers for those working in education. We are two academics, one with a primary teaching background and one with a secondary teaching background, one of us identify as First Nations and one as white, settler. We write on the Country of the Wurundjeri-Woiwurrung of the Kulin Nation.

Sophie: One of the most striking parts of the report I thought was the way in which the stories the young people tell about their experiences highlight how the education system doesn’t often connect well with what is going on in young people’s lives. For example, where Binak talks about all the tasks she is doing to help the family at home and how that impacts her capacity to be engaged and energised at school.

I think in schools we tend to either feel sorry for students like Binak because we see them as having too much to do outside of school and that can fall into a deficit view of the student and their family or we see her as not having her focus in the right place, that she should care more about her studies and be able to see the long term benefit of that. But Binak clearly talks about how important her family are to her and so an educational solution for her is not to take her away from those connections but to try and work for strengthening the connections she has and building those towards the school.

I wonder whether finding opportunities for families like Binak’s to be better connected to schools and the resources schools have could also help to support the family.

Melitta: Interesting points raised here, Sophie. Often as an Aboriginal educator within the system and particularly, in my work and teaching on community, it was interesting to observe that White settler teachers often did not consider the family relationship and demands outside the school yard. The teachers I observed would ignore or not get to know the story of Binak and rather simply bundle them into the ‘too hard’ basket.

On the flip to this, I often wondered about the relationships and purportedly, partnerships, that schools and school leaders are to develop and nurture with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and communities. For me, the real takeaway from the report are the stories themselves. The pure honesty and raw emotion evident as each person share the complexities they have faced and yet, the overriding and undercurrent theme of family trickles in and out of the lines. The power and strength of family – the way the relationships feed and inform the individual truly draws the reader in. I wonder if schools and school leaders, classroom teachers and ancillary staff – if they knew the true stories of the importance of family and how influential they are on the child/student and their engagement with schools – I wonder if this was acknowledged and recognised if half the battle of participation and engagement would be won?

Sophie: Yes, I think perhaps one of the key issues in the current moment is that the focus on administration and testing in schools can take teachers away from the long and hard work of building relationships. This is especially an issue when the legacy of the education system’s treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families means teachers have to make extra efforts to build trust and ensure school is a safe place. Recent research has shown that Indigenous students have consistently experienced a range of different forms of racism in schools over the last three decades. It is also known that racism affects school attendance and academic achievements.

This is an experience that Murrenda in particular articulates in his story in the Ngaga-dji Report. He describes how he felt that the school curriculum didn’t see his people and taught instead a ‘happy white history’. This is a common experience for First Nations students and something Gumbaynggirr scholar Lilly Brown found when she interviewed high school students in New South Wales.

The other thing Murrenda noticed was that school taught him that ‘people hate blackfullas’. This is part of an over-riding deficit (and racist) discourse that Indigenous students have to contend within schools and something you have investigated in policy, Melitta. What would you say are the implications of this for educators?

Melitta: There is an ever-present quandary in the education system. Today’s policies have finally answered the call from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to include Indigenous histories and cultures. However, on the flip side, it has failed to recognise key flaws within the system and society. That is, the policies fail to recognise the cultural gap, ignoring how many White settlers do not know the shared history of colonial Australia which has been silenced within schools and institutions for decades.

The historical purpose of education – to create the ideal citizen – and in turn, perpetuate the status quo privileging the ways of the coloniser has ensured that dominant ideologies, biases and assumptions are maintained. These silences have fed the notions of racism, deficit and the coloniser’s sense of superiority held by White settlers.

The principles brought forward in the Ngaga-dji Report act to counter and disrupt these very social conditions evident in colonial Australia today. They are succinct and to the point. The principle of self-determination acts to privilege Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ voices that come from a lived experience. The stories shared in this report privilege the voices of Indigenous voice; the very people that the policies are written for and about but whose voices are silenced and not evident in the policies themselves. And finally, those voices of youth cannot be heard without the knowledge shared and held within family and community. For we do not speak as individuals but as a collective.

Hence, educators and systems need to learn to listen. To not just hear the voices but actually listen to what is being said and shared. It is only through listening and being willing to listen to an alternative worldview that true reconciliation and understanding can occur. The stories shared within this report begin those conversations and provide a starting point; inviting educators to reflect on the ways in which they respond to these truths.

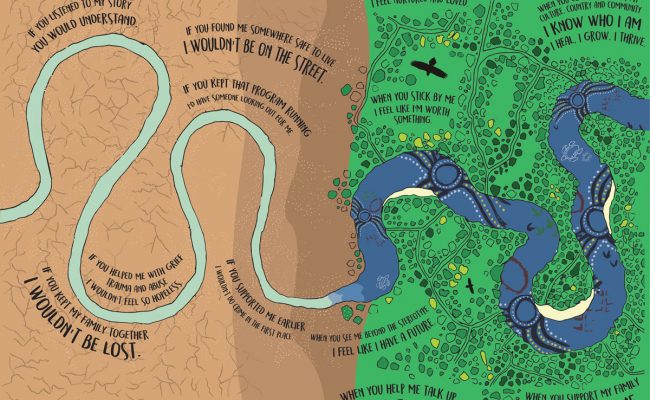

Cover image: Jacob Komesarof, Koorie Youth Council

Read the rest of Reflections on Ngaga-Dji: listening for change, edited by Sophie Rudolph and Claire Loughnan

Read the rest of Reflections on Ngaga-Dji: listening for change, edited by Sophie Rudolph and Claire Loughnan

If you enjoyed this special edition, subscribe and receive a year’s worth of print issues, the online magazine, special editions and discounted entry to our literary competitions