The stories shared in the Ngaga-dji Report portray a youth justice system that is overly punitive and entrenches cycles of disadvantage for Aboriginal young people. They make clear that this system is broken and contributes not only to the overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the criminal justice system, but also to the ongoing disempowerment of Aboriginal young people, their families and communities. But the report also paves a way forward, providing solutions that are grounded in the principles of self-determination, youth participation, culture, family, Elders and communities. In this article, we discuss the challenges raised in the Ngaga-dji Report for legal professionals and others working in the youth justice space more broadly. John is a Professor in Human Rights Law and Samara is a proud Awabakal, Worimi and Biripi woman and is a non-practising lawyer currently working in Indigenous education. We write on the Country of the Wurundjeri-Woiwurrung of the Kulin Nation and the Country of the Biddegal of the Eora Nation, respectively.

Samara: What was most apparent to me reading the report is the dissonance between the system’s attempts to ‘support’ the young people and their lived experiences in the system. I think this highlights two key challenges. Firstly, that the views of young people are not seriously considered in the decision-making that affects them.

For instance, it wasn’t until Binak reached Koori Court that she was asked what she and her family needed. This should have happened much earlier in the process to prevent her from ending up in court in the first place. Young people need services and programs that empower them rather than shatter their sense of self-worth; no child should have to feel like ‘bits of me were broken off and tossed away’. But young people cannot feel empowered if they are not involved in decision-making.

This relates to the second challenge: determining the ‘bests interests of the child’ as the guiding principle in decision-making that concerns young people. Despite this being a well-established principle, there is no single definition, and the experiences of the young people shared in the report highlight the inherent ambiguity in its application.

The legal system in Australia remains overly paternalistic, particularly in its treatment of Aboriginal children and young people. The system needs to shift its focus from protection to self-determination but to do this, magistrates and other legal practitioners need to broaden their understanding of the challenges facing young people and the best way to empower them and their communities. To this end, they should complete ongoing cultural safety training under the guidance of the local Aboriginal community, trauma-informed practice training, as well as training in child rights theory and practice. Magistrates should also consider how they can apply the principles of Koori Courts to mainstream courts in order to make the process more inclusive and community centred.

In addition, I would argue that the best interests of Aboriginal young people are not just limited to maintaining their connection with family, community and culture. This is critical of course, but it must go beyond maintaining connection to also supporting and empowering families and communities themselves, because we know that the wellbeing of Aboriginal young people is interconnected with the wellbeing of their families and communities.

John: Like Samara, the thing that struck me most when I read the report is that we just don’t know how to listen to Aboriginal children and young people who find themselves stuck in the youth justice system. We have lots of laws and principles about the need to respect the views and cultures of Aboriginal children, but we don’t really have proper systems to allow these children to express their views.

The comments of Mirrim Nga-Ango were really revealing, when he talked about the relevance of being ordered to do the ‘Ropes’ course by the Court:

Why? I don’t know how they thought climbing some bloody trees would change me. It’s like trying to fix a broken leg with a band aid.

I’m sure the people who designed the Ropes program had good intentions. But for so long, this has been the problem with programs that are supposed to benefit Aboriginal children. They reflect what I call a welfare-based approach, a paternalistic model that says that these children are vulnerable and need our protection and that we, as the white experts, can fix or help them.

It is the same idea that led to removal of Aboriginal children from their families. But this model forgets that the voices and views of children need to be heard and taken seriously in any measure that is designed to empower and support them. It forgets that children have wisdom and understanding and that we as adults within the youth justice sector have to create better systems and processes that will support these young people to become active participants in developing solutions to the challenges they face in their lives.

This has to begin with the simple act of listening. For me, the Ngaga-Dji Report starts this process. Hearing the voices of young Aboriginals demands personal reflection and is a call to action for all professionals who are serious about wanting to make the lives of these children better. It also requires that the universities and professional bodies that have responsibility for the training and ongoing professional development of lawyers develop educational programs and implement processes that enable lawyers to understand the significance of listening to Indigenous children, to recognise the current obstacles that inhibit their ability to express their views and to develop system new models of participation and engagement that will allow for the voices and views of Indigenous youth to be heard and taken seriously.

Samara: John is exactly right; the report is an opportunity to change the stories of young people and to break the cycles of disadvantage. For legal professionals and others working within the youth justice system, responding to this call for action requires taking a holistic, whole-of-family approach that aims to strengthen communities, broadening the focus beyond just the individual. It also means creating space for youth participation and ensuring that youth voices inform decision-making at all stages of the process, not just when a young person ends up in court.

They have shared their stories and solutions, now we need to act together to create change.

John and Samara: In order to take up this call to action, we encourage our colleagues in the profession to reflect on your current practices and consider how seriously and deeply they engage with and consider the voices of young people. And then act because something has got to change, so what will you change in your day to day practice to show that you are listening to the voices of young people?

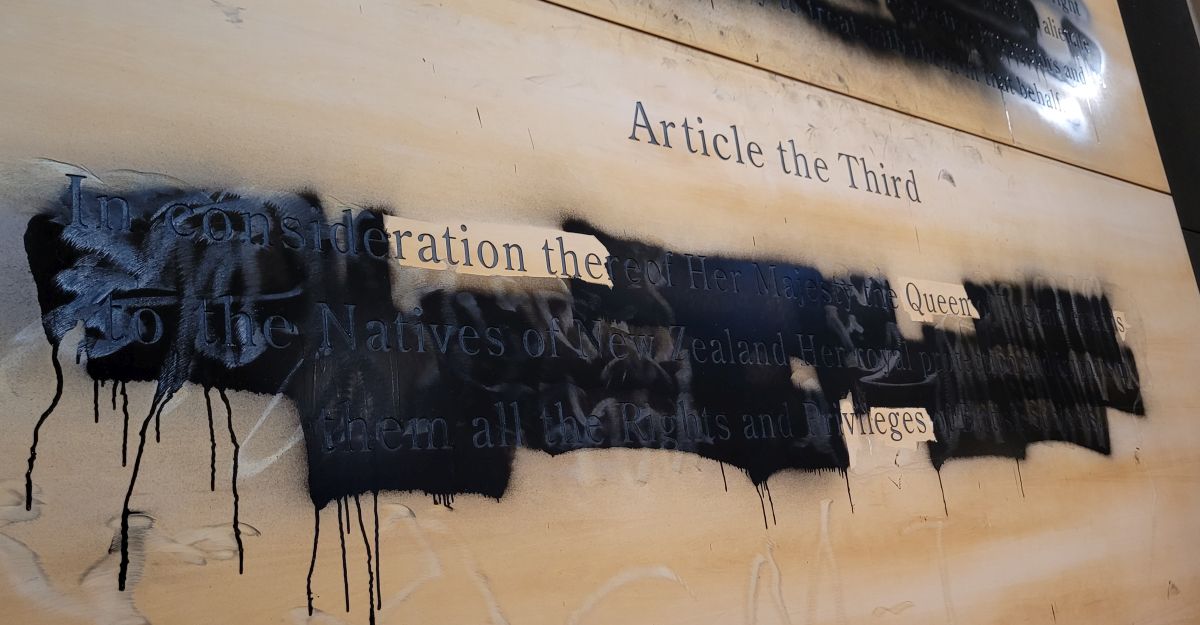

Cover image: Jacob Komesarof, Koorie Youth Council

Read the rest of Reflections on Ngaga-Dji: listening for change, edited by Sophie Rudolph and Claire Loughnan

Read the rest of Reflections on Ngaga-Dji: listening for change, edited by Sophie Rudolph and Claire Loughnan

If you enjoyed this special edition, subscribe and receive a year’s worth of print issues, the online magazine, special editions and discounted entry to our literary competitions