These reflections on the Ngaga-dji Report come at a time when the decision to build a new youth justice centre in Cherry Creek, west of Melbourne, has been scaled down but remains an inappropriate model for responding to the needs of Aboriginal children, many of whom are often caught on the residential care-youth detention-adult prison pathway.

The persistence of penal responses reflects the ongoing structural impacts of colonisation. As criminologists, and as someone working in the youth justice system, we know that institutional racism leads to higher rates of policing, police violence and incarceration of Aboriginal kids. This has long been reflected in Australian statistics, with deaths in custody and police brutality disproportionately affecting Aboriginal communities and Aboriginal kids. Meaningful change requires alternatives to incarceration and a willingness to listen to the voices of Aboriginal children and their families and communities.

The choice Ngaga-dji presents is for governments to support children outside the ‘justice’ system by rejecting punitive approaches leading to kids being placed in ‘concrete boxes that teach them to be angry, lonely and violent’. It is a call for change both within the criminal and youth justice system as well as among Criminologists. Changing the traditional focus of criminology requires attention to place and to Aboriginal knowledge and learnings.

Bonnie Dukakis is a proud Gunditjmara woman born and raised on Gunai Kurnai Country, now residing on Wurundjeri Country and working as Aboriginal Education Leader at Parkville College, Youth Justice Centre. Claire Loughnan and Faith Gordon are Criminologists. Claire works and lives on Wurundjeri and Woiwurrung country of the Kulin Nation; and Faith is originally from Northern Ireland, now living the land of the Yalukit Willam clan of the Boon Wurrung people and working on the lands of the Kulin Nation.

Bonnie

The stories and experiences shared in the Ngaga-dji Report are not dissimilar to those told by our children and young people in custody today. Since its release, in August 2018, too many have continued to ‘graduate’ within the youth justice system from one facility to another, or for some, more extremely into adult custody. This remains a stark reality and expectation for many of our children, unless punitive approaches are changed and alternatives acted upon.

I hear of children and young people becoming all too familiar before the court, being told that this sentence must ‘beat’ their last, as it obviously hasn’t taught them a lesson. This continues to diminish the experiences of trauma and acceptance that has led them there in the first instance, often alongside involvement with ‘child protection’. This response leaves children with extended sentences beyond those around them, creating further disconnect from their family, community and culture, building their reliance upon a new norm around custody – becoming institutionalised.

These punitive responses need to be replaced with a holistic healing model that supports the growth and development of Aboriginal children and young people through a holistic approach like the social and emotional well-being model described in the report. This model places the child at the centre, with agency over their life, valuing connection to culture alongside connection to family, community, physical and mental wellbeing, not instead of, and not without. This calls for buy-in from the community to lead, and for government to relinquish some level of power, enabling trust in new approaches developed by community. We know that building on a child’s connection to culture builds on their strength and resilience, it helps them heal in a way they haven’t been afforded before. Allowing communities to take back control, responsibility and care for these children creates new opportunity and development, leading the way for community-driven self-determination in changing a system that historically was designed to exclude.

Claire

The kids in this report speak openly about their experiences of family separation and cultural loss, often resulting from placement in ‘resi’ care and youth detention, showing how a prison pathway is built by the system, for Aboriginal kids, their families and their communities. But their stories also reveal the strengths of community, rather than replaying a story of deficit. As criminologists, we cannot continue to privilege Western law and criminal justice systems, using statistical research that reinforces a deficit model of Aboriginal communities while claiming to respect Indigenous laws and learnings.

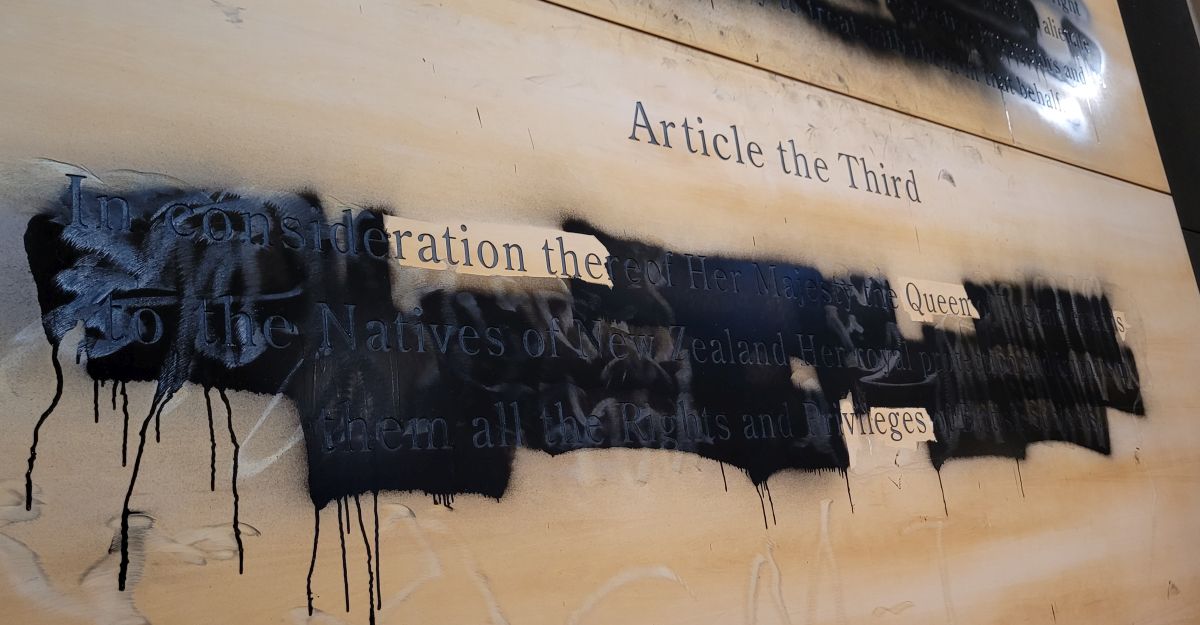

Settler-colonial Australia was built on the erasure of Aboriginal place and knowledge, marked by repressive, punitive control of Aboriginal communities. Historically, criminologists have been complicit in their relationship with the criminal justice system, often failing to challenge its foundations. This report is a call for criminologists to pay attention to place and healing so that there can be a real change to the criminal justice system and to criminology as a field of research. Upholding the significance of place is what holds community together. As Wakka Wakka and Komumberri scholar and elder Mary Graham tells us: ‘the land is the great teacher; it teaches us not only how to relate to it, but to each other.’ For healing to occur, place-centred responses must focus on children and community and must be grounded in culture and locality.

Faith

Youth justice and child protection systems are ‘closed off’, with the public often mainly receiving most of their information about them from media reports. Yet the voices of children and young people are rarely heard and acknowledged in the media. Just as critical criminological research records, champions and gives a voice to the ‘view from below’, the Ngaga-dji youth-led report places children’s and young people’s voices and experiences at the forefront. As one young person outlined, although ownership of their personal story was of the greatest importance to them, adults often spoke for them, rarely listening: ’It didn’t matter what I screamed at them, they wanted to tell my story for me, decide for me, know what was best for me.’

The Ngaga-dji report features confronting contemporary realities of violence experienced by many Aboriginal children and young people. It proposes locally-lead community-based responses that can support children and young people in the context of their community in a holistic manner, tailoring services directly to needs. Locally managed alternatives to the formal justice system would make a difference in communities. This can be compared to the restorative justice community-based models in Northern Ireland such as NI Alternatives, which have been operating for over two decades. The model is community-led and utilises non-violent, innovative approaches to doing justice within local communities. Ngaga-dji highlights the central importance of community to Aboriginal children, young people and their families.

Conclusion

Ngaga-dji is a call to action, described as a ‘call from the heart’, so that Aboriginal children and young people can thrive in Victoria. It is up to us as criminologists and those working in the criminal justice system to ensure that these voices are heard and acknowledged in public debates. Many critical criminologists have long included the experiences of Aboriginal children who have been victims of police violence and discrimination. But more work is needed. As Stephen R. Covey once said: ‘Most people do not listen with the intent to understand; they listen with the intent to reply.’ Childrens’ voices in Ngaga-dji are clear, strong visions of the change they want to see. Their stories of resistance and strength are a call for change and a rejection of the structures that produce violence. We need alternatives to punishment which are community-focused and strengths-based.

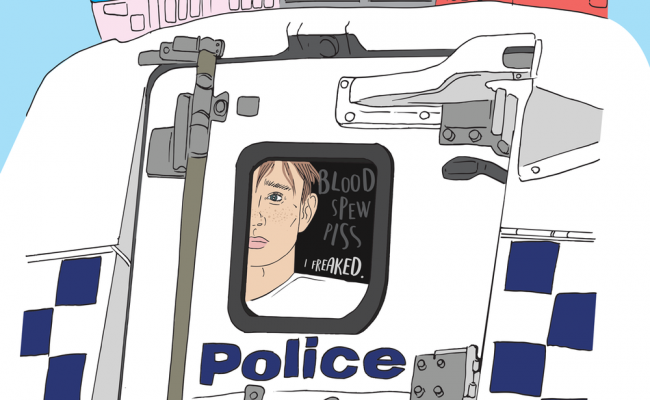

Cover image: Jacob Komesarof, Koorie Youth Council

Read the rest of Reflections on Ngaga-Dji: listening for change, edited by Sophie Rudolph and Claire Loughnan

Read the rest of Reflections on Ngaga-Dji: listening for change, edited by Sophie Rudolph and Claire Loughnan

If you enjoyed this special edition, subscribe and receive a year’s worth of print issues, the online magazine, special editions and discounted entry to our literary competitions