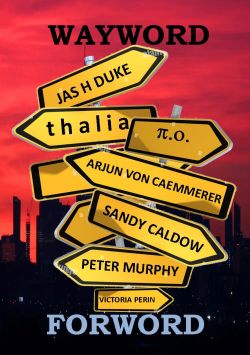

In May 2023 6 poets, Jas H Duke, Peter Murphy, thalia, Sandy Caldow, Arjun von Caemmerer, and myself, held an exhibition of concrete poetry “Wayword Forword” at the Nicholas Building in Melbourne, curated by Victoria Perin. It attracted a large number of people over its 3 weeks on the wall, and generated a lot of discussion about the place of concrete poetry in the annals of Australian art history and poetry. [An anthology of the same name by Collective Effort Press was also produced to commemorate the occasion].

In May 2023 6 poets, Jas H Duke, Peter Murphy, thalia, Sandy Caldow, Arjun von Caemmerer, and myself, held an exhibition of concrete poetry “Wayword Forword” at the Nicholas Building in Melbourne, curated by Victoria Perin. It attracted a large number of people over its 3 weeks on the wall, and generated a lot of discussion about the place of concrete poetry in the annals of Australian art history and poetry. [An anthology of the same name by Collective Effort Press was also produced to commemorate the occasion].

Concrete poetry in the late 60s + early 70s made a very brief appearance in the Australian art & literary canon — long enough for it to be given a quick glance before deciding to move on, to the next big thing (about 20 years after it had already made its mark as a movement on the world stage). Ironically enough, its poetics, aesthetics, and practise had (and still has to this day) a lot to offer the digital age, and should have been a major player in the visual and language stakes, but there is very little evidence of that direct influence, and its place was usurped by Web Designers, design programs, algorithms, and DIY aficionados, who for the very first time in their lives had their very own personal “advertising agency” at their (disposal) finger ///// tips. The concrete poets of the day didn’t disappear however, and kept working at the art and poetry of it, resulting in what Noel Macainsh rightly observed [in “Making the Picture Real”, Westerly, March 1975] was nothing more than a jumble of unrelated “successive expressions”, heavily weighed on the side of individual achievement. And before anyone here realised (or wanted to acknowledge) that concrete poetry also had a “sound” component (that was and could be of interest to experimental musicians say) it was ridiculed (as Ian Hamilton Finlay pointed out) as “child’s play”, “infantile” cos “it was seen and not heard”. Code-breaking, word arrangement, sequencing, permutations, combinations, and various other “word-play” (in all its manifestations), has been the bedrock of poetry since time immemorial, but aside from the acknowledged “lyricist” practise of rhyming on cue, at “the end of the line”, or every 2nd or 3rd or 4th line etc, its spatial component remained and remains invisible, and considered (too frequently) unworthy of serious consideration and reflection, let alone of academic interest.

Collective Effort’s contribution to the advent of Concrete Poetry in Australia at the time was the anthology “Missing Forms” issued in 1980 and edited by Peter Murphy and myself. The saga and struggle of its coming into being is another sad story best left to later. In an important exhibition in 1989 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Brisbane [curated by Zurbrugg, “Visual Poetics: Concrete Poetry and Its Contexts”] Nicholas Zurbrugg explained that “Whereas Futurism, Surrealism and Expressionism were all centred in particular cities, concrete poetry flourished on a world-wide scale … ” [and] “Rather than existing ‘between’ poetry and painting, new forms of verbal/visual creativity appear to occupy and identify creative spaces ‘beyond’ poetry and painting, as word, image, graphics and colour combine with typography, paint, photograph, photocopy and computer”.

About a year before our exhibition at the Nicholas Building, an unexpected, rare, and rather idiosyncratic book of poetry “Purgatorio Re-placed” by Alex Selenitsch was published, involving all manner of concrete poets as characters within its text. The poem begins with a plea for help, and success from the Muses “O Muses! Help! Help!”, and sets out “How it is written, and for what reason”, namely an Odyssey of Post World War 2 migration. Selenitsch sez he had “three histories / to plait together: OZ / post-war displacement / and a 14th century text”, a text “put to paper 500 years / before the First Fleet”, and he wants the text (as he sez) “to sing”. In 1986 Selenitsch read Tom Phillip’s [the English concrete poet] translation of Dante’s “Inferno”, but instead of stopping there Selenitsch went on to read Dante’s “Purgatorio” and realised that it was set [in the 12th Century!!!!] somewhere in the Southern Hemisphere [and further] “was astonished to find, in Canto I, a mention of magpies, [and] a constellation of 4 stars…” [read, the Southern Cross]. Being an Architect by trade, the idea manifested itself in an earlier guise in 1995 in an exhibition “Dante Down Under — the Purgatory Suite”, consisting of 4 pictures of furniture, at separate arms of a Cross, which (as he put it) “ positions the ‘translator’ around the periphery of a spiral that connects the four arms of a unilateral cross. Read clockwise, the arms are ‘scholar’, ‘poet’, ‘editor’, and ‘critic’; the Scholar’s Shelves, the Poet’s Chair, the Editor’s Bed-end and the Critic’s Chest”. This sketch hovers above a seven-stepped ziggurat representing the Mountain of Purgatory. Jenny Zimmer in her review in The Age [“Furnishings of Purgatory”, 21/6/95] tells us “Selenitsch thinks about space diagrammatically … ” and the exhibition could be read as a commentary on his experience of migration, dislocation and the cultural cringe … He uses “a red rubber stamp to represent the mountain” for example, and a second stamp only faintly observed thru the paper that reads — “Made with European ideas only” which not so long ago was the motto stamped on Australian-made furniture as a mark of quality.

In Canto II of Selenitsch’s “Purgatorio Re-placed” he sees shiploads of “souls being brought to Purgatory [read post-war Australia] to purge the causes of their sins”, and they are greeted by various “shades” — quite a few of whom are or connected to “concrete poets” or poetry. The Shades see the “white ships” from Europe coming and greet them all, ostensibly to show them around this land down under [read Australia]. — Bizarre!!!! — Selenitsch sez “I circle me with sentences. / Magically” [his notion of inspiration presumably] “when a line / is pulled out of my thoughts / another line springs up”. The book talks of his own journey out here and he grants himself a “perspective” and “permission” to structure an Australian sermon. Such a self-serving “commission” however i find difficult to swallow — even DH Lawrence was humble enough to realise the difficulty involved for one coming from a land of Intruders. As Lawrence put it in Kangaroo “Tabula rasa. The World a new leaf. And on the new leaf, nothing”, presumably awaiting Selenitsch’s arrival to continue some kind of European sermon, and (strangely) take the higher ground, pointing out to us [the readers?] that he knows “we” [us?] “despise magpies” [a paper tiger if ever i saw one]. One wonders who he is addressing, in this Epic “new” age. The very projection of European fantasies and mis-tellings are mapped onto the very notion of “blankness” in this country. As Simon Ryan [in The Cartographic Eye, Cambridge University Press 1996] tells us, explorer after explorer in journal after journal (trying to describe what they are / were looking at) make stunning “confessions of [their] linguistic ineptitude” — “the discovery of a ‘new’ land creates immense pressures on the language of the newcomers” he sez. The sublime evoked in Leichhardt’s journey provokes a “wordlessness”, giving rise in him to “feelings that I cannot attempt to describe […] beyond all description” — and so he further stumbles linguistically into inadequate clichés to finish the job description can’t supply. Johnathan Swift satirised the whole enterprise of colonisation [in On Poetry: A Rapsody] “So Geographers in Afric-Maps / With Savage-Pictures fill their Gaps; / And o’er uninhabitable Downs / Place elephants for want of towns”. Simon Ryan tells us that “antipodeanism” was a legitimate field of “ambition” for Explorers, and as such a solo enterprise [my italics] — the blank areas on maps serving “the cartographer’s imagination” and allowing it “free rein”. [Further] antipodeanism “is the silent partner in the construction of the Aborigine” also, and the act of omission aids and abets their predicament. As Christopher Marlowe put it [in Tamburlaine] “ … when holy Fates / Shall stablish me in strong Egyptia, / We mean to travel to th’ Antarctic pole, / Conquering the people underneath our feet … ”. In Selenitsch’s cantos, “Dante and Virgil see a white ship coming over the horizon”, and so become for Selenitsch “the book to re-write” [my italics] and as Selenitsch’s “desire for ceremony” was “removed at the equator” (as he said) i too won’t stand on ceremony — however invisible that horizon at sea.

As the poem progresses “further into the Mountain” [of Australia, metaphorically] a number of “Shades” begin to reveal themselves — Note: all these Shades are White, all European, all Male, and quite a few dead Concrete poets. They come out of the shadows, light up the landscape and greet Virgil [“a Poet, of Classical times”] and Dante [our Hero / the writer?]. By Canto VI the first Shade comes forward, and it is Ian Hamilton Finlay [the Scottish concrete poet] who in real life had his own landscape and troubles to write about in Scotland at “Little Sparta” where he for over 4 decades literally carved and littered his “garden” in Roman script, and concrete poem after concrete poem set in his gardens. Finlay sez to Virgil “I embrace you as a brother”, and confesses to having used bits of his Latin lines of poetry in his garden — from the “Eclogues”, “Georgics, and Aeneid. But this encounter instead of being brought forward by Selenitsch to comment on “landscape” and “flora and fauna” is brought forward to lament Art’s oscillating fortunes at the hands of Industry, militarism, and religion … lamenting the shift “from Classical to neo / Classic” and the slippage away from “ornament” [read art-for-art sake?]. When Finlay asks “V” [the now familiar appellation for Virgil] what he is doing here [in Australia] V sez “I’ve just been / through Hell. I’m here / to enable inspiration”. How strange that this European “Shade” should be qualified to show anyone around Australia — methinks. Finlay’s “concrete poems / sculptures have … been widely displayed in gardens and public places, by river-banks and the sea, and many were designed to incorporate or reflect the natural light and colours of outdoor environments” as John Jenkins explains [in “New Waves in Concrete (in Australia)” Overland No 114 (1989)], but not of this landscape i should point out. As Finlay sez himself “Little Sparta is a garden in the traditional sense” [my italics]. And although there is a lot to admire in Finlay, e.g. “A PEBBLE is a crumb of the Ancient Geology” or “The art of gardening is like the art of writing, of painting, of sculpture; it is the art of composing, and making a harmony, with disparate elements”, his PEBBLE “never had so much dignity as when it was employed as an alpha by the old Pythagoreans” [referencing Pythagoras’s tetractys]. Instead of enlisting Finlay on issues of the natural environment Selenitsch concerns himself with Finlay’s war machines and militarist poems and motifs — strange indeed!

I find throughout Selentitsch’s Purgatorio a whole series of missed opportunities, and mis-firings. Altho he doesn’t reference Alan Riddell in his book, it must be remembered that in 1970 Alan Riddell was the first concrete poet to publish a concrete poem in a major daily, his “The Three Voyages (and a prayer) of Captain Cook” published in the SMH as part of Captain Cook’s commemorative voyage of discovery in 1770 — a literal-reading being “hms endeavour, hms resolution, hms discovery, ___ SAIL SET FOR THE GREAT SOUTH LAND AND MAY THE VOYAGE BE FRUITFUL”.  When Riddell eventually published the poem in his book of concrete poems Eclipse [in 1972 by Calder & Boyars] the space [the gap] between the deck and mast (that holds the sails in place) was replaced by the words “o god”, underscoring the notion of the “discovery” of Australia as being sanctioned by a Christian-European deity / “God” — rightly implicating Christianity in the endeavour, effacing and subjugating any prior Ownership or agency to anyone else, outside “God’s will”. I find it strange that Riddell was omitted from Selenitsch’s evocation of discovery by concrete poets. Alan Riddell was born in Australia, and won the Heinemann poetry prize in 1956. He later founded the poetry review Lines in London, which he edited from 1952 to 1955 and from 1962 to 1967, was for several years a sub-editor on The Daily Telegraph, and his book Eclipse is credited with being the first “one-man volume of concrete poetry” to be published in England. He also edited the anthology Typewriter Art, and had arranged quite a few retrospective exhibitions of visual poetry: “Photo — Poetry”, exhibited in London, Sydney, Amsterdam, Edinburgh, Brussels and Liechtenstein. He died in 1977 in London aged 50. His influence on Selenitsch must not go unacknowledged here either, and i find it odd he was omitted from the cavalcade of poets and shades. The discovery of Australia by a concrete poet, would have been news indeed, and a great starting point — a lost opportunity.

When Riddell eventually published the poem in his book of concrete poems Eclipse [in 1972 by Calder & Boyars] the space [the gap] between the deck and mast (that holds the sails in place) was replaced by the words “o god”, underscoring the notion of the “discovery” of Australia as being sanctioned by a Christian-European deity / “God” — rightly implicating Christianity in the endeavour, effacing and subjugating any prior Ownership or agency to anyone else, outside “God’s will”. I find it strange that Riddell was omitted from Selenitsch’s evocation of discovery by concrete poets. Alan Riddell was born in Australia, and won the Heinemann poetry prize in 1956. He later founded the poetry review Lines in London, which he edited from 1952 to 1955 and from 1962 to 1967, was for several years a sub-editor on The Daily Telegraph, and his book Eclipse is credited with being the first “one-man volume of concrete poetry” to be published in England. He also edited the anthology Typewriter Art, and had arranged quite a few retrospective exhibitions of visual poetry: “Photo — Poetry”, exhibited in London, Sydney, Amsterdam, Edinburgh, Brussels and Liechtenstein. He died in 1977 in London aged 50. His influence on Selenitsch must not go unacknowledged here either, and i find it odd he was omitted from the cavalcade of poets and shades. The discovery of Australia by a concrete poet, would have been news indeed, and a great starting point — a lost opportunity.

By Canto VIII, things get even more interesting in Purgatorio; two other “Shades” John Reed and [his adopted child] Sweeney Reed [from Heide fame] come forward. Heide [the location of the art gallery in Melbourne] is / was the central location of perhaps the most intense period of Modernist practice in Australia, and the home of both John and Sweeney Reed. Note: Sunday Reed (John’s partner) does not make an appearance in this masculinist work, despite the fact that she too is dead and would have qualified as an important “Shade” (methinks). Her omission i think pointing to a poverty of critical understanding — another lost opportunity [more later].

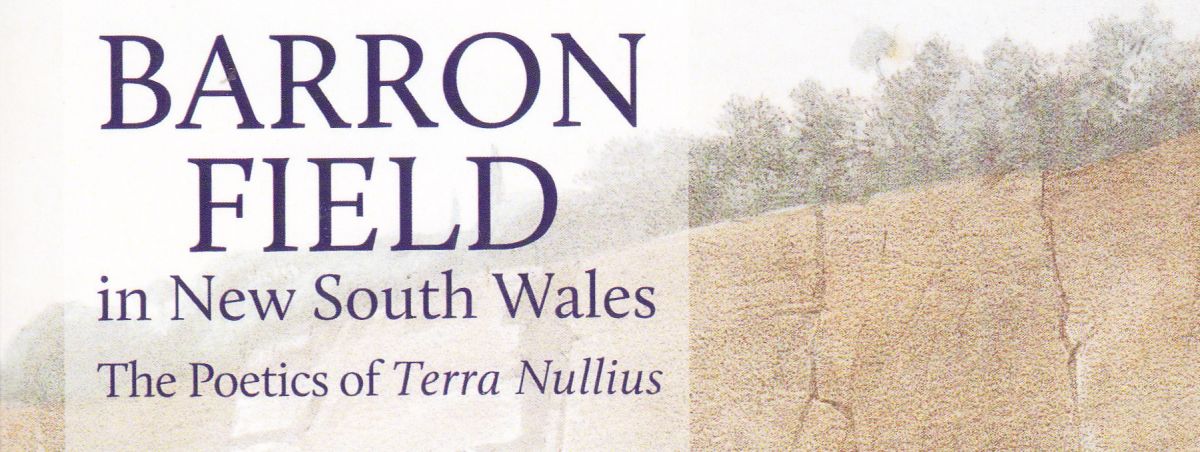

In the middle of the “Wayword Forword” exhibition, Brendan Casey brought in a copy of Thomas H Ford & Justin Clemens’s recent [and magnificent] study of Barron Field in New South Wales [Melbourne University Press]; an Englishman, poet, judge and botanist. In 1817, Barron Field was appointed judge to the Supreme Court of New South Wales. As was then the custom, he received a grant of land for his effort, 2000 acres (809 ha) at Cabramatta, and a salary of £800. He also subsequently had the distinction of having published the first “book” of poetry in Australia, First Fruits of Australian Poetry, in 1819. The literary circles in London he moved in included Charles Lamb, William Wordsworth, Coleridge and Leigh Hunt amongst others. But here in Australia his poems were more often looked on as “doggerel”, or as the political activist John Dunmore Lang said (of Barron Field) a “weak silly man who fancied himself a poet born”. Michael Robinson in The Sydney Gazette said, Field was a man who had no scruples calling “himself the first harmonist” of Australia, even tho he couldn’t “even make his lines chime”; a “Viler and more revolting egotism” could not have proceeded from the pen of such a man — an assertion not unfounded (according to the papers at the time) coming from a “modest enough” man such as the then current “poet-laureate” [Michael Robinson] who had already “produced a number of truly poetical pieces … ”. And to enjoy this damn tomfoolery a little longer, Barron Field’s “utmost efforts” it was said, could produce “no more music than that which could be elicited by the most regular rattling of the drum-stick”. Not very popular this Barron Field, who “distributed his trash in private”. I won’t bore you with the poetry of a 2nd rate Romantic, you can look up Clemens and Ford’s book for that, or as Charles Lamb asked him in 1817 “…and how does the land of thieves use you? Have you poets among you? Damn’d plagiarists, I fancy, if you have any”. But Barron Field did stay long enough to pronounce on a crucial bit of law (proper) — namely the legal notion of “terra nullius” in Australia.

Governor Macquarie in 1819 built a tollgate [for a pop of 30,000 in Sydney] across Parramatta Road — a farthing for every sheep, pig and goat that moved along the roads, outside the city perimeters, with double toll fees on Sundays. Barron Field knew his legalese and his counsel was considered wise. The previous Judge to the Colony [Justice Bent] refused to sit in judgement on whether or not the toll was justifiable, and personally refused to pay the toll — rattling the chain at the toll gate and going thru it willy-nilly without paying. Barron Field [“the highest legal authority in the land” as Clemens + Ford put it] later advised the said Governor Macquarie he had “exceeded his powers in exacting tolls… Without backing from the British parliament”. As in Jamaica [another “conquered island”] the English King alone had a right to levy taxes — no one could impose taxes on inhabitants that hadn’t been “conquered”, and since Australia was [as the legal fiction said] “peacefully settled”, the silent premise itself didn’t allow him to impose taxes. So Field’s legal opinion on Colonial powers embodied the very doctrine of terra nullius, making him “the first legislator of terra nullius” no less. The judgement rested on whether the land was acquired by conquest or not. The real fear being, as in the cry from the American Revolution showed (“no taxation without representation”) an unconquered people could only be taxed by their legitimate assemblies. Field said New South Wales had not been acquired by conquest or secession, but taken or occupied as deserted “uninhabited”. It had not been “invaded”. As such this was the “first stirrings of representative democracy on Australian soil” (“no taxation without representation”). The idea that nobody “occupied” the land before the British came, was the foundation of settlement here. In May 1785, Joseph Banks was questioned about sending convicts to the Great South Land. He said: there were very few people around the coast, and the interior was most certainly empty — uninhabited, literally a land without owners, a terra nullius & a tabula rasa to boot — no one to negotiate with! Henry Reynolds tells us that the instructions given to Cook was that he could only take “possession” of “uninhabited lands” else wise it could only be done with the consent of the Natives. No consent was given, and Cook stuck his flag pole in the ground anyway! When “Field’s legal reasoning was confirmed back in London” it set “in train a series of statutory and administrative changes aimed at re-establishing the colony on a new and more consistent constitutional footing” — I didn’t read Thomas H Ford & Justin Clemens’s book, i devoured it! I immediately saw, that the whole issue of “terra nullius” (in White colonial history and literature) was bookended by “two poets”, namely Barron Field, and Sweeney Reed, and umbilically tied to the notion of terra nullius & the blank slate. As Henry Reynolds put it, in his book Why Weren’t We Told?, Reynolds struck up a friendship with Eddie Mabo, a groundsman and gardener at James Cook University, and told him that nobody actually owns land on Murray Island. It was all crown land. “Eddie Mabo was stunned. [ … ] How could the whitefellas question something so obvious as his ownership of his land? — It was then (over sandwiches and tea) that the first step was taken which led to the Mabo judgement in June 1992.” As Bernard Caleo put it in a review “Beware the lawyer poet who takes your land and beautifies his theft with literature”.

But as well as being an author of the legal fiction of terra nullius, Field was also the author [as i said before] of the first book of Australian poetry to be published in this country, in 1819. First Fruits of Australian Poetry is, to judge from the poems, fairly fruity stuff. Thomas H Ford and Justin Clemens’s mission in this book is to compare and contrast Field’s two modes of writing, legislative and poetic, and to show us what one mode makes stark in the other and vice versa. They identify Field’s arrival as marking a change in the culture of colonial Australia from an authoritarian penal colony to a more liberal society, and link this change to the culture of the writers, the Regency Romantics, who constituted Field’s literary community back in England. This book, then, is a poetic reading of Field’s legal judgement and a “close reading” of his poems, which takes seriously the power of writing within Australia’s colonial history. In fact Field was the first to use the word “Australian” here, in his poetry.

In the late 1930s when John and Sunday Reed established Heide as an Artists’ space, it was Sunday Reed who insisted that the “landscape tradition” in Australian art was not over, and she urged and insisted the likes of artists like Sidney Nolan, and Albert Tucker kept it as a central element of their aesthetic practice — this despite the general trend away from Australian Impressionism, and towards Cubism, Abstraction, and Surrealist modes of expression. Sunday and John Reed were well aware of the importance of landscape, and had literally followed in the footsteps of Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, who in turn had followed in the footsteps of Louis Buvelot [from Fitzroy] who went out as far as Heidelberg [a stones throw from present day Heide] to paint the Australian landscape en plein air. Their impact on Australian art was immense! Sweeney Reed was the birth child of Joy Hester and ostensibly Albert Tucker, who for all sorts of pressures and reasons John and Sunday Reed adopted as one of their own. Sweeney’s biography and history is firmly entrenched in the rise of Concrete Poetry in Australia.

For any young man to find himself in such a long and important tradition, amongst some of the giants of Australian art, as Sweeney had, it was a big ask; a big ask to find a space to “work” in. He flew off the handle often and his delinquency became legendary. In 1964, in an effort to break the cycle, he went to London, and met the likes of the concrete and sound poet Bob Cobbing, and other figures acquainted with the British Poetry Revival [coming out of the 1960s underground poetry and alternative publishing and culture scene of the swinging 60s]. He got a job at Better Books bookshop on Charing Cross Road, where poetry readings, happenings, film and art installations were held in the basement. While there, he saw an exhibition “Between Poetry and Painting” curated by Jasia Reichardt that included the works of Ian Hamilton Finlay. Back in Australia Sweeney set up “Strines” Gallery [it being that exaggerated broad phonetic pronunciation for “Australians”] in Carlton. The Age [15 Aug 1972] ran an article headed “Sweeney Reed — demon art man”. [Quote] “The new kid on the block, with big ideas”. In the words of friend and poet Russell Deeble “Sweeney always saw himself a[t] Flinders Street station — it was through him that activity occurred”; the populous train station being a mixed metaphor (also) for a delinquent’s hangout (to this day). Throughout 1967, Sweeney and Deeble held a series of poetry readings and workshops in the basement at Strines that were packed to capacity. As Trevor Vickers remembers, “They were trying to take the dour aspect out of the poetry and make it sort of sixtiesish … a bit like a musical event”. Concrete poetry at the time seemed to be antithetical to the “new abstraction” in Art [such as Pop Art (that was slow to catch on here) it seemingly being allied to too much figuration against the onslaught of abstraction]. By ’69 Sweeney’s advocacy of experimental poetry came to the fore, with a fully realised solo exhibition of Alex Selenitsch’s concrete poetry — an Australian first. Sweeney also initiated a series of small press ventures, that embraced and distributed publications by international artists and poets such as Ian Hamilton Finlay; limited edition prints, poster poems, catalogues, journals, anthologies and books. The “Broadsheet” poster series initiated and funded by Ian Turner [from Overland] featured numerous artists involved with Strines, and in No. 3 “Where are all the flowers going?” featured poems by Sweeney Reed and Russell Deeble alongside “the first concrete poem to be printed in Australia”, Alex Selenitsch’s “up/dn”. Its realisation came to Selenitsch when using Letraset to label a drawing, he noticed that the abbreviations “up/dn”, could be strung vertically into a ladder — “up” being the reverse of “dn”. Over the years it became a precursor to further works regarding ladders.

After Strines Sweeney studied printmaking at the Victorian College of the Arts, producing two and three dimensional text works. Whatever may be said of Sweeney’s work it’s fair enough to say that his sense of the avantgarde was not simply a case of “art for art’s sake” or dispassionate journeys into avantgarde Modernism, but was informed by what had (and was) still evolving out at Heide, (whether they knew it or not) a sense of “content” and “context”, and in particular its relationship to the “Australian landscape tradition” that Sunday Reed insisted was “not” over. This is in stark contrast to a lot of other concrete poets who were spawning individual avantgarde / Modernist / art-for-art’s-sake creations, on a hit and miss basis. Sweeney’s relationship to the “Landscape tradition” however was not acknowledged at the time or ever appreciated, and it suffered (like most of us) from serious analysis and or guidance. His one great support was Barrett Reid [elder friend, and poetry editor of Overland] who more than anyone in Australia made room in the magazine for concrete poetry. Whether or not Sweeney knew what he was doing, or anyone else did for that matter, is purely conjectural, and ultimately not directly relevant to the work’s final significance or impact. I can’t help but feel that the “childish” attitude of concrete poetry sidelined Sweeney during his lifetime [something we all felt & feel collectively] and contributed to his neglect in the cannon of Art Australia, becoming perhaps only a “footnote” to a fading Heide itself, for him.

To illustrate his contribution to the “landscape” tradition, and to highlight the shortfall Selenitsch [in my view] made / makes, i’ll sit on 2 poems by Sweeney. The first one is his concrete poem “escape”

On a simplistic level, the poem is a one-word event, and “childish” in the extreme, just like when one simplistically takes the word “jumping” and makes it appear as j u m p i n g . You can see that the letter “e” in Sweeney’s poem is in the act of scaling the wall at night; escaping. But what if the word isn’t “escape” here, but the word “escapee”? Where could the other “e” be???? If it’s not on the page [in its “art” frame] it can only have “escaped” somewhere — “off the page” perhaps, i.e. somewhere else, and the only other physical place it can be in, is in the environment itself, in the landscape — somewhere in Australia [the place of the poem’s birth], just like the escaped convicts from the many settlements, dotted around the continent, or the one established at Sorrento [some 30 something years before the establishment of the settlement on the Yarra by John Batman] [who it should be noted was also bankrolled by John Reed’s grandfather, to go out there and “discover” Melbourne]. Most of the “escapees” during the settlement at Sorrento were never seen or heard of again, except for one “William Buckley” who survived to tell the tale, and who became our conduit, “our translator” between the Aboriginal people and Settlers. I think it extraordinary how the medium of concrete poetry can literally incorporate the whole of the environment outside a poem’s frame and gallery walls, and make its context [here] more meaningful, [as opposed to overseas] i.e. where it was created, and still now resides — literally breaking the bounds of its framing and prison doors. From a psycho-analytical point of view [something i personally loathe to consider normally] the poem can also be seen as a personal statement by Sweeney to “escape”, to be freed of both language and art and the interpersonal relationships out at Heide. I don’t know what he thought he was saying or doing in this respect in his poem, but feel that an anthology of his work and poetics is long overdue, and should be placed in the cannon of Australian literature and art as an ongoing and uninterrupted landscape tradition. Was it he who was to be the escapee? Was the word “escap” deliberately not a complete word, or completable [yet]??

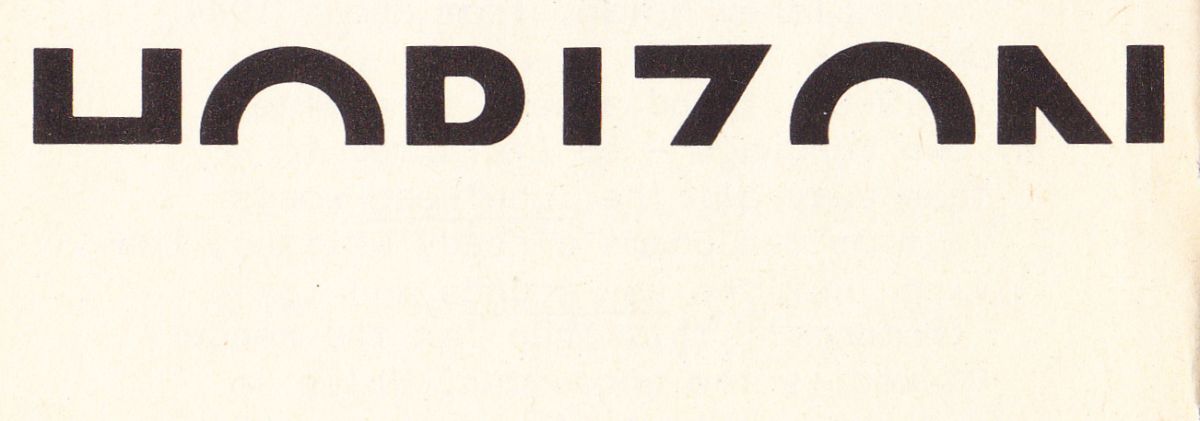

The next poem of his, i want to examine, is perhaps Sweeney’s most widely known, appreciated, and significant of all, variously entitled “Impounded Illusion”, or colloquially HORIZON, and was exhibited at Tolarno Galleries in May 1977 in a solo exhibition “Moments of Mind”.

John Jenkins [in Overland No. 114] described the poem as being “cut in half horizontally” and “an example of his gift for elegant minimalism and poetic evocation”. Alex Selenitsch over several decades has reiterated this description in much the same way, virtually always describing the work as “a single-word poem; a rising HORIZON represented by only the top half of each letter, such that the word appears to emerge from an actual horizon line” — rising and falling being a metaphor of sunset. A horizon is certainly seductive, and Maria Semple reminds us that when our eyes are softly focused on a horizon for sustained periods, our brains release endorphins in much the same way as running. But seen from the perspective of the “landscape tradition” i find that persistent description inadequate. When it was exhibited in the “Born To Concrete” exhibition out at Heide [beat.com.au], HORIZON was described as meaning “wherever you go, there’s a horizon”, as tho Sweeney thought we must need reminding; — at the end of a movie, the Hero & Heroine look at the horizon and see the sun sink or rise, or else stand on the beach, and meaningfully *sighs* — “I want to know what’s out there” [said meaningfully]. Geometry tells us that the distance of the horizon — i.e. the farthest point the eye can see, before the Earth curves away from the viewer simply depends on the height of the observer. For example, if you stood atop Mount Everest 8,848m high, the horizon would be about 370km away. Or as Edwin Hubble said of it “The history of astronomy is a history of receding horizons”. But to see Sweeney’s poem in that way alone, is to deprive the “eye” of looking. The elephant in the room for Sweeney’s HORIZON is not a sunrise but what it actually foregrounds; [answer] “nothing”, the devastating blank below the half letters, the “white space”, devoid of all feature, flora, fauna, people, and/or smoke from campfires. This is Terra Nullius / Tabula Rasa itself — a legal fiction.

Sturt [the explorer] writing in his journal, could see that there was something there “The plains were still open to the horizon, but here and there a stunted gumtree … seemed placed by nature as mourners over the surrounding desolation … over which the silence of the grave seemed to reign”. As Paul Carter put it, the country “was not empty, but replete with languages and directions”. Sweeney Reed’s achievement was to draw-paint-write and depicted the unsayable, unpaintable. Something that no one else, no other painter, in the Australian landscape tradition had [has?] done, and as i intimated earlier Sweeney thus bookends the concept of Terra Nullius initiated by that other “Australian” poet Barron Field who introduced the concept / doctrine into our legal system.

Strongly associated with the HORIZON are those moments when the land itself, resists being “stared at” — creating a kind of “blindness” [namely] during a MIRAGE. In the words of Sturt, the mirage on the horizon floats “in a light tremulous vapour” and it “deceived us with regard to the extent of the plains [and] hid the trees, in fact, from our view altogether”. The desert’s blind “glare” for an outsider causes, a collapse of ownership, recording, making the very act of mapping; no longer possible, literally obliterating the foreground, when as William Cowper [the English poet] sez “the eye: / […] posted on this spectacular height. / Exults in its command”, and with an “uplifted cane” enables one to point to an object of desire. The importance of the HORIZON for an explorer is for “a looking into space” a looking “forward” into Time. As Paul Carter [in Living in a New Country] sez, an “explorer-writer’s inability to advance the narrative smoothly is intimately connected to [their] inability to name phenomena accurately” and [further] [and this is a horrendous idea] “Scaling down horizons to the width of a page […] enabled one to model reality, to plan invasions”. Joseph Bank’s complained that “[Cpt] Cook sailed too much, and stopped too little”, in creating an “outline” of Australia with a blank heart and as such became perhaps the first to start the terra nullius ball rolling. To own is to explore [Sturt’s journal of exploration 1844-45] “Let any man lay the map of Australia before him, and regard the blank upon its surface, and then let me ask him if it would not be an honourable achievement to be the first to place foot in its centre”. John Jenkins notes, that “Central to his [Selenitsch’s] early work was a preoccupation with time”, and further “It seemed to him [Selenitsch] that the immediately apprehended image/poem might be able to remove time from art” and “If that were possible, the object or poem could exist, shorn of temporality, in an instant or continuous present”, not anything i would subscribe to may i say. [To continue] “These inherently metaphysical speculations underly much of [Selenitsch] work”. In this context HORIZON [the poem] is seen merely as a kind of “panorama” — basically concerned with the emotional state of “awe” [in the original Romantic sense], or else robbed of its historical context. This metaphysical notion naturally wedges itself inside “awe”, and “centres” the viewer in the “middle” of the line / the horizon, giving one the illusion of centrality, in much the same way as Tom Roberts once hoped his paintings would be exhibited “at eye-level” on the wall of a gallery. The feeling that the observer is “stationary” while the environment is everywhere 360°, is common, and the depiction of the horizon through the “cartographic eye” centres the observer symmetrically left and right of the line, and immobilises them — a pause of reflection [perhaps] at the empty-blank space before them; below them, obliterated. Take the metaphysics out of it, and the metaphysical glare, and we might perhaps begin to “see”.

Sweeney Reed took his own life in 1979, and Selenitsch in his book unabashedly says that Sweeney tells him [from the grave?] “when you make it back / to the living, can you finish / one of my works for me?” this self-serving arrogant posthumous commission seems astonishing to me, as tho the poem remained unfinished! In Selenitsch’s exhibition at Heide “LIFE/TEXT”, Selenitsch offered “his” own [extended] version of a “Z-Horizon” which for me totally misses the mark; at best a secondary work of little importance, despite curator Linda Short soft Scottish lilt telling us “Sweeney died rather untimely in 1979, quite young, and Alex always felt that perhaps that project wasn’t quite finished, so he’s made these new works quite recently in response to his work”.

The importance of this review for me is the foundation on which Selenitsch’s book Purgatorio rests, starting from all sorts of “givens” / “axioms” that do no more that re-hash popularist notions of “landscape” and exhibit a poverty of critical analysis. Alan Riddell’s Captain Cook’s ship would have been a good starter, and Sweeney’s HORIZON an excellent opportunity to take the sublime into (or out of) the glare of the landscape, or to find it there, having to deal with it. Failure to undertake a rigorous contextualisation of concrete poetry risks distorting the historical record. In 1968, the anthropologist William Stanner spoke of “the great Australian silence” surrounding the harsh realities for Indigenous people of European settlement. To get our part in that history accurately, is the least we can do. Aboriginal people didn’t and don’t need to be told about HORIZONS, but we [newcomers] have to re-break that silence, for our own sakes.

The tragedy of this project is that i think Selenitsch had already in one of his earlier works re-written his own version of the “horizon”, whether he knew it or not, or was conscious of it or not, and in Sweeney’s lifetime, whether he was consciously influenced by it or not. As John Jenkins says “Selenitsch is regarded by many of his peers in Australia as one of the doyens of concrete poetry”. From my perspective Selenitsch’s pre-occupation with “the language” as a new social value, may have had a lot to do with his migrant background. His paring-down of language to “single words” is quite a common strategy of migrants, as is the desperate shuffling around of letters and words in sentences, like boxes in a warehouse. Born in Germany of a Russian/Austrian/ Ukrainian family, he has never really felt “Australian by habit” and, insulated from Melbourne within his Russian-speaking household, it was still possible for him to feel very much a European he sez. 33 years later he reads Dante’s Purgatorio and marvels “at Dante’s story // of boatloads of souls” coming to the underworld. This “obvious” writing-back to the Empire poetics is an old practice that most writers and poets in Australia have long dispensed with — a kind of reaction of the cultural cringe variety. Selenitsch’s cultural precursors are very much taken from European Modernism, and (at the time) often characterised by “a lack of content”. This retreat from “content” in art and poetry, was a natural reaction to a language that had literally been mutilated by the war in Europe. In truth, as Adorno saw it, there could no longer be any poetry after Auschwitz, but this was not the case in the Australian context — if anything it was and is a struggle from a multilingualism between unequals and equals — another kind of Modernism altogether.

In an unpublished essay “On the poetics of Alex Selenitsch” i wrote around 1995 i linked his “Monotones” [concrete poems] to the migrant experience in Australia. I sent him a copy, but got no reply. In the essay i linked the common idea that the landscape was often described by migrants as being variously “monotonous” [or as Inge King once put it, to Sandy Caldow, “untidy” in its monotony] and it seemed to migrants (like Inge) as tho it had been flattened by a nuclear bomb. Sturt [the explorer] in his journal talks about it not being the describer’s fault, but the land’s failure for not providing recognisable differences on which language itself could operate. Around 1968??? “Selenitsch embarked on an intermittent lifelong project of the “Monotone” [concrete] poems. As he said [initially] he selected a deliberately “blank” word, “monotone”, and subjected it to various treatments, arrangements, permutations, and transformations, and he was less interested in the banal meaning of the word, and more in the actual process of exploration [exploring?] itself — “Every style in art is a camouflage” [Ian Hamilton Finlay]. — “… the total effect is anything but monotonous” [as i said in my essay] “cos the very act itself … contains within itself a coming to terms with, a surrendering to the reality of, the fact of, and in a sense a “coping” with, the reality” [here]. “In a very real sense the MONOTONES were / are Alex’s very own Tv set”. His arrangement of the word MONOTONE into square boxes is quite literally reminiscent of what happens in a factory or depot, and the incessant arrangement over a lifetime is suggestive of an unease of sorts. To fully appreciate what he thinks he is doing i think it instructive to have a listen to him. He sez, he gives “the reader enough clues to set up a game and then reconstruct and experience the flash that occurs when you see something. Because the flash itself is the subject matter (not the thing that is seen)”. If we go in search of that FLASH in the series [in the first 8 monotones done in 1970] we find A TONE, NO ONE, the MOON, and in the middle of a full square sheet of white page, an astounding deviation

( )

a pair of lone brackets, with absolutely nothing inside them “almost as tho the word “monotone” had completely disappeared or bled into the paper. In “normal” writing the brackets would be used to encapsulate a word, or phrase, or paragraph, or (dare i say it) “a line”, and in this sense it is an “invisible line”, perhaps even a “horizon”, or in the context of post World War II migration, the glare over a landscape having been completely obliterated by a nuclear bomb. In the arena of textual practice brackets are an “aside”. [This is an aside]; perhaps this “is the uranium that runs under my [Selenitsch’s] project”. Is that what he wanted to suggest in this work?? Or wanted to say?? Depict? And even if we asked him, his answer can or could be taken as irrelevant, after all how would HE know what it “meant” / “mean”! William Gilpin [a theoretician of the picturesque] tells us “The pleasures of the chase are universal. A hare started before dogs is enough to set a whole country in an uproar”. And why not this uproar for us?! It must be remembered that the concrete poetry scene in Melbourne was relatively small, and there was a lot of cross-fertilisation going on, with influences firing-off in all directions. As Selenitsch puts it in his Dante “… I see / a twig from a tree / which might produce a forest // then a harvest…” GUX did, Astra-aliens did also … How long does “an incubation period” have to take to be??? And is “conscious intent” really any guideline? Selenitsch confesses that he does not see concrete poetry as having “any clear linear or historical development”, aside from the usual linkages to Mallarme, Apollinaire, Schwitters, the Dadaists and Futurists, the fifties and sixties major British concrete poets, Finlay, Bob Cobbing, John Furnival et al … i do [lots]! When we were doing the workers magazine 925 in the 1980s we had no idea that what we were also doing was recording the arrival of the computer and the digital age into the workforce, it only became obvious years later, and in retrospect. So what are we doing now? [God knows!]

In terms of the Australian landscape, Barron Field in effect created “a semiotic blank” for the “Whiteman”, to have it at “his” leisure, and to project upon it “ostensibly innocent descriptions” that would by default preclude the existence of an occupying population of any significance, namely the Aboriginal people who had already scribbled and sung and ventriloquised all over the landscape for 60,000 years or so. Interestingly enough, for Clemens + Ford the very notion of terra nullius “as a specific doctrine of international law” drew significantly on “older literary material, most notably that founding text of Western civilisation, Virgil’s Aeneid” — we come full circle, i guess. Alberico Gentili [Oxford Professor of Law] argued that “the seizure of vacant places is regarded as a law of nature” in that “the law of nature […] abhors a vacuum”.

Virtually all our discussions at the exhibition [of “Wayword Forword”] on and about HORIZON presumed that the issue at hand was “land”, but Justin Clemens + Thomas Ford’s scholarship on Barron Field opened my eyes to an entirely different angle altogether, namely to that constant companion on board ship at sea ( ) was the HORIZON, and the Equator. In truth for EVERYONE on board those migrant or convict ships the first such instance of a HORIZON to the antipodes to be contemplated was over WATER. “The higher the observer’s eyes are from sea level, the farther away the horizon is from the observer. For instance, in standard atmospheric conditions, for an observer with eye level above sea level by 1.70 metres, the horizon is at a distance of about 5 kilometres” [Simon Ryan], and again the space in the foreground i.e. under the surface, for the migrants coming out here was “blank”. As Lewis Carroll put it in “The Hunting of the Snark” — “He had bought a large map representing the sea, / Without the least vestige of land: / And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be / A map they could all understand …” The notion of the HORIZON was every migrant’s constant companion, and even more so, passing that “invisible line” at the EQUATOR where Selenitsch stood in ceremony.

One of the recurring metaphors used by Explorers (forced to find linguistic solutions) was the recurring image of the DESERT as a SEA. Seeing the desert as Sturt put it “like the waves of the sea in endless succession”, elsewhere imagined as yet an undiscovered ocean. The effect of this parallelism in Simon Ryan’s critique was to “homogenise the landscape”, to create it singular … a monotone … monotonously. “… indeed [all] deserts, are the same”. Or to quote from Sturt again, “A dark gloomy sea of scrub without a break in its monotonous surface met our gaze”. The final tabula rasa as Simon Ryan sees it is “If the landscape fails to provide variegated signs which may be interpreted” [and from Sturt’s journal again] “From the spot on which we stopped no object of any kind broke the line of the horizon; we were as lonely as a ship at sea …”. Oxley [the explorer] “nothing relieving the eye but a few scattered bushes, an … the view was as boundless as the ocean”. [Leichhardt] “There was no smoke, no sign of water, no sign of the neighbourhood of the sea coast; — but all was one immense sea of forest and scrub”. And blinded by a mirage, Stuart wrote that he “never saw it so bright nor continuous … one would think that the whole country was under water”. Now what is remarkable about Clemens + Ford’s scholarship was unearthing a crucial exchange in England around 1819 about “Whether a ship was poetic?”. Thomas Campbell claimed it was the sea, the effect the ship had in the water as it ploughed through it, that poeticised the image, not the ART or design of the ship per se. Lord Byron said it was the ship that conferred “its own poetry upon the waters”, as the sea was “a somewhat monotonous [my italics] thing to look at”. These otherwise “empty expanses” were “humanised” by the ship’s presence. In other words, the image of a ship on the water with its horizon was what was beautiful [“a ship’s the only poetry we see”] and for all intents and purposes all else below the horizon “vacant” — just like, on land — nothing below. Clemens + Ford put it beautifully “England is hence ‘the island’ that turned every land into a sea”, and for Barron Field the power of “these imperial horizons” were the site

where Nature is prosaic,

Unpicturesque, unmusical, and where

Nature reflecting Art is not yet born.

As Clemens + Ford said, “without careful attention to Field’s poetry, something essential about the foundations of Australian culture and society may continue to pass unrecognised […] not [just] of judge-made law, but of poet-made law”.