They call it a wall, but it is a funny kind of wall. You might have seen them around. Crushed basalt rock sandwiched between sheets of reo. The sides go up, then the rock is added from the top. That’s the job of the gang, to hand the rock along the line and then up to the person on the ladder. I’m sure there are more efficient ways of doing it – elsewhere they’d be prefabricated beforehand. But that’s not the point. The wall is designed to give us young people something to do and I suppose in that sense it’s a bit old-fashioned, like our great-grandfathers and great-grandmothers when they took on their trades and joined their guilds and drank milk from clear glass bottles. It’s grunt-work, yes, but there’s skill in it too.

Most often you see these walls along the edges of freeways, but our wall doesn’t border anything. For a long while we supposed a freeway would follow. A boss stops by occasionally to check on the alignment and point again in the direction it should take. If there are any deviances it is only because of the landscape: a submerged boulder, an escarpment, a hill. The boss only ever speaks to me; I’ve been gang leader since the start. I don’t trust the way it happened – a system of stones in a bag – but then maybe it was not so random? I’m not saying I’m smart, but I’m smarter than the others. They took me on as leader and the idea of me not being leader or there being some kind of system of rotation, say, hasn’t come up since. There are twenty-two of us, a random number. Male and female, they don’t discriminate. The average age is twenty. I have just turned thirty. But we have one who is fourteen, too. A few have paired off – it’s only natural. I turn a blind eye. If it doesn’t interfere with the work, I say, then I have no right to interfere with it.

Our days hardly alter: we zip open our tents, stoke the fires, cook breakfast, begin. Re-pitch the tents as the wall advances, cart the reo from the pile the flatbed truck has left and the rocks from the pile the tip truck has dropped. The further the wall travels, the more carting there is; often this carting takes up most of the day. But then, sometimes, suddenly, a new truck with new reo or a new tip truck with new rocks will arrive and drop a load ahead of us and then for days or even weeks there is little carting and much building and before we know it we have outrun those piles and are looking at the flat horizon again.

Sometimes my people ask Why a wall? and I need to be careful with my answer. We’re preparing for something, I say, something that has not yet happened but will happen at some future date that the planners have forward-guessed. It is my duty to take charge. Idle hands do the Devil’s work, I say, when I’m shaking their tent poles in the morning.

I have instructions about how many metres to average per day but unfortunately the weather is often against us and there is no contingency for it. What we lose in the rain we must make up in the sun. Sometimes it rains for days. A van comes by and drops raincoats – they want us to put them on, risk a cold, pneumonia even, for the sake of a few precious metres. But I need to look after my team. Zipped up in our tents, breathing the fuggy air, fiddling with our phones, playing Celebrity Heads or Charades, we soon enough wish we were working. It’s good to grow the hunger, teach gratefulness for the job you have and not dwell on the job of your dreams. The young are slow to understand and I am here to help them. Houses are earned by working on walls, a boss once said. I believe it.

I should tell you that I am in love with Emma – it’s not like love’s forbidden but I am her supervisor and it can’t be right. The moment I saw her I knew that I would fall in love with her. She was carrying a tote bag with a picture of a cat on it, a Siamese cat, its eyes bulging and distorted. A loping walk, a long torso, a wide waist, small breasts. She can lift basalt all right; we all stood back and watched. But I also need to tell you that lately the desire to barge in on her tent and reprimand her for something, anything, has become completely unbearable. I don’t know how much longer I can resist. Isn’t that strange? I want her to sleep in, in my mind I beg her to sleep in, some mornings when I wake I plead to god that she will. She is my best worker, she has proved it from day one, and that’s why my love for her is so pure. Supervisors love the workers who make work easiest for them. She has eyes only for the job, she doesn’t watch herself, wonder what she looks like or what people might think. She doesn’t sleep in; she never slackens. In the evening she won’t party because she knows she has to be fresh. I try to catch her out, but my Emma is unimpeachable. I want to reprimand her, deeply, I can’t tell you how deeply, with all my heart I want to tell her off. It would be a broadening and strengthening of our bond. But if she gives me no reason?

The bosses convene each spring to discuss the progress of the walls. They are all men: smart, experienced. Good business backgrounds, good business heads. Big heads, actually, because of the stuff they must carry in them, their necks grown fat in support. They hand down the figures and give us the forecasts. They are bosses in the managerial sense, in the sense that they manage our affairs. Walls, fences, roads – everything the machines could have done but which they have sensibly given to us. We’d have nothing otherwise. The walls are working, they say; the people at rest is a restive thing. We prefer to look forward, not back. The wake-up call, the washing, the dressing, the breakfasting; the heaving, the lifting; all are designed to wrap us up in a sweet culture of forgetting. That, surely, is the benefit of work? To put a fog over the days, to not let you wonder about what might have been but to graciously accept what is. Be grateful, says the sign above my tent. We are simple creatures like that.

But sometimes, true, we must go back, to repair the damage the idlers have made. Barbarians, with the glassy eyes of too-much-beer-in-the-afternoon. They do it in the night because they’re not good in the mornings. They clip the reo with bolt cutters and let the rocks tumble out. They throw them around for fun. They push over whole sections. They celebrate their idleness by attacking our work. The idea of a job offends them, especially a job like this. They say they have the advantage over us of using their idling to imagine and that imagination frees them – from work, they say, especially. I say in reply that I for one have not lost the capacity to imagine, that I imagine all sorts of things, for example that our wall will one day join up with the others and go all the way around and that on that day an important politician will cut the ribbon and that you will not be worthy of licking his boots.

I take a smaller crew back down the line – preferably with Emma in it. The city sits squat in the distance, held down by its yellow haze. I love those days. A small team, no tents, no cooking; real workers, pure workers, off in the morning and home late in the afternoon. One morning down there we found an idler sleeping; the demolition had tired him and he’d laid down to rest. Blond, tanned, well-fed. I pushed him with my foot. He was as surprised as us. Why do you do it? I asked. Can’t you celebrate your idleness without interfering with our work? They wanted us to feel useful, I said, so they gave us this wall to build – what is that to you? This caught him by surprise. Because it’s stupid, he said. To you, I said, glancing at my team and especially at Emma to see if they and she especially agreed. You’re happy having nothing to do, I said, we’re not: we like getting up in the morning. Huh, said the idler, and he stood and straightened his clothes. So you like doing dumb work for a boss, he said, and perpetuating the old order? But this is the new order, I said. He didn’t answer – just walked off. Slowly, like he had nowhere to be. We watched until he disappeared and cursed the time we’d lost.

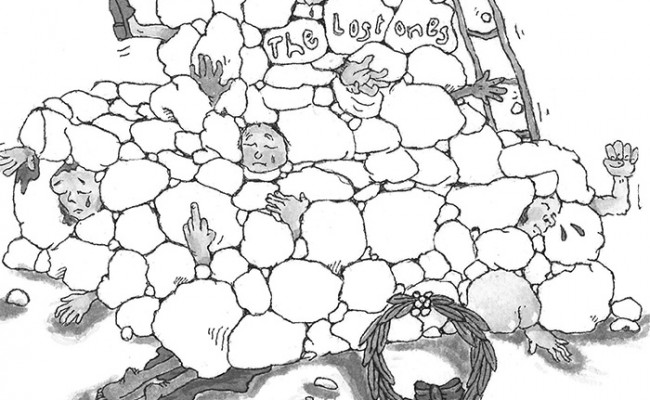

After a downpour, when the rain clears and the trucks return to drop more reo and rock, when we zip open our tents and see the blue sky and the steaming earth and our glistening, unfinished wall, there is not one of us that does not give thanks. We idled, for days, but what did we get out of it? We played stupid games, stared at our phones. People need something, anything, to hold hard against the tide. Far better this than the idler’s life, with its vacant stare, loose ends, stupid idlerisms. We have built kilometres, my team alone, we have proved our strength and resilience. We are not narcissists, malingerers; we are able-bodied humans: we can build walls along with the best. They underestimated us, the critics. They thought we were a lost generation – but now, here, look.

Read the rest of Overland 233

If you enjoyed this piece, buy the issue