Look, it hasn’t been a great year for women artists. But let’s be frank: it very rarely is.

In January, the Australian Book Review launched its inaugural Gender Fellowship, which asked a writer to produce an article on gender in contemporary Australian letters, only to later decide that none of the applicants had met the criteria ‘in sufficiently new or compelling ways’. Leaving aside ABR’s poor judgement in launching a gender fellowship dictating recipients must write about gender issues, the magazine then announced that the initial applicants weren’t good enough on International Women’s Day.

The Australian music industry continues to be dogged by an all-too-predictable lack of diversity. The team behind Triple J’s Hottest 100 called 2017 a year ‘worth celebrating’ because of the number of women in the top spots, but this development was only cosmetic: according to the Equality Institute, all-male acts still made up 78 per cent of the poll. Meanwhile, Hack’s annual ‘Girls to the Front’ investigation showed that Australia’s major music festivals are still struggling to get anywhere close to gender parity, a fact routinely accompanied by protestations that all-male line-ups are simply a consequence of good taste.

Since 2004, the NGV’s blockbuster Winter Masterpieces series has celebrated the likes of Dali, Picasso, Klimt, Monet, Degas and other male European masters. The 2017 instalment was Van Gogh and the Seasons. In 2018, it will be a highlights package from MoMA featuring, once again, Dali, Picasso and van Gogh, alongside Pollock, Duchamp, Matisse, Lichtenstein and Koons – just one woman, Lyubov Popova, is mentioned in the official exhibition announcement. According to Elvis Richardson’s Countess Report, a benchmarking project on gender equality in the Australian contemporary art sector, women make up 73 per cent of art school graduates, but only 34 per cent of artists exhibited in state museums and galleries. Women are also noticeably underrepresented by commercial galleries. ‘The closer an artist gets to money, prestige and power,’ Richardson says, ‘the more likely they are to be male.’

There are many other examples we could cite from just the last twelve months, all demonstrating the conspicuous absence of women from senior creative roles, organisational boards, selection panels and prize committees, as well as their low representation in major exhibitions, award ceremonies and media coverage. Together they demonstrate a persistent lack of recognition, reward and respect for women across the breadth of Australian arts and culture.

A number of recent studies have sought to understand why women continue to be consistently underrepresented, despite making up a proportional share (or more) of audiences, students and emerging practitioners.

The Australia Council’s 2012 Women in Theatre report revealed minimal improvements in the representation of women in creative leadership roles over the previous decade. In fact, there was evidence that the situation had deteriorated. The report identified issues that were ‘frustratingly similar’ to those addressed in equivalent studies from thirty years prior: the dominance of men in artistic director roles (accompanied by a lack of transparency around selection processes that is often passed off as creative autonomy), lack of opportunities and career progression for women, and the inevitable toll of unsociable work hours and precarious employment, which adversely affect women who, according to the ABS, continue to take on double the childcare responsibilities that men do.

In September 2015, Music Victoria released a report that described five barriers to women’s careers near identical to those outlined in previous studies: a lack of paid work, the casualisation of the workforce, the gendered nature of caring responsibilities, limited access to opportunities and the ‘confidence gap’ – all of which collectively contribute to a pay disparity that undermines women’s music careers in the long term.

According to the results of David Throsby and Katya Petetskaya’s latest survey of Australian artists, ‘the income gap between men and women is wider in the arts than the average gap across all industries in Australia. This gap appears to be especially evident for female writers, visual artists and musicians.’ While the average national gender pay gap was 15.3 per cent in 2017, in the arts it is a whopping 30 per cent. That’s in keeping with a recent US report into gender and pay in the broader cultural economy, published by HoneyBook in October this year, which put the pay gap for creative freelancers at 32 per cent.

In late 2015 came Screen Australia’s Gender Matters report, looking at the underrepresentation of women in key creative roles in the film and television industries. The same barriers were again identified: a lack of pay equality, a lack of confidence, the gendered nature of childcare and the dominance of men in key decision-making roles (investors, distributors, network executives, festival programmers and so on).

These reports make for grim reading, not just because of their conclusions – persistently inequitable pay in a sector where so much work is already gratis, greatly truncated careers that rarely make the leap from emerging to more established practice and a pernicious absence of women in high-profile positions – but also because of the dreadful sense of deja vu they provoke.

The reports describe, with depressing predictability, minimal (or negative) improvement in the proportional representation of women in key roles and point fingers at the same broad obstacles – barriers that have changed very, very little in thirty years.

Consider the following sentiments on childcare from the Women in Victorian Contemporary Music report produced by Music Victoria and released in 2015.

I am young and not yet thinking about children but there will come a time when [I will have to consider], how can I be the best manager and travel/attend gigs if I have children? … This is not something that the men in my workplace have had to have a second thought about.

And similarly, from the Women in Australian Film Production report produced by the Women’s Film Fund in 1983, ‘there is the perpetual question “What will you do with the children?” as though you haven’t thought of it before applying for the job – it’s a question never asked of men.’

On the topic of career progression, ambition and recognition, 2015 interviewees observed that ‘Male egos [take] credit for female initiated achievements … [T]here is a lack of recognition professionally due to male dominated industry.’ Likewise, the 1983 interviewees note that in a male-dominated industry, ‘you are expected to prove yourself more’, ‘you have to push harder to be taken seriously’ and it becomes ‘easy to get stuck in the support role’.

In both reports, produced more than 30 years apart, managing caring responsibilities and a creative career is identified as a very real concern, one that is sometimes heartbreaking to negotiate, and which exists alongside a range of other more insidious inequalities.

Almost without exception, the same issues – caring responsibilities, confidence gaps and a lack of opportunities, recognition and income – have been identified by equivalent studies dating back to the 1970s. For all the radical ways that the making of culture has transformed over the intervening decades – namely reduced material barriers courtesy of the relative affordability of digital media – on this critical issue things haven’t budged an inch.

So what has gone wrong? Why have several decades of policy and research failed to make much meaningful difference to the experiences of women artists?

Part of the answer lies with two cultural paradigms that have come to dominate cultural policy and, in many cases, have exacerbated the obstacles women face.

One is ‘excellence’ – often spoken of in the same breath as its bedfellow ‘innovation’ – which has become the primary criterion for judging the value of publicly funded arts and culture. The other is the concept of ‘creative industries’, which uses positive economic activity – from tourist dollars to city branding and urban regeneration – as one of (if not the) rationale for government support for cultural funding. A quick scan of the websites of relevant government departments and funding agencies reveals just how widespread and pervasive these discourses are.

The two concepts have been around long enough to have earned their fair share of scorn and critique. In a 2015 essay for Overland, and again in When the Goal Posts Move, part of Currency House’s Platform Paper series, Ben Eltham argues that the excellence paradigm is little more than dog-whistle politics for the arts. Excellence and innovation seem like self-evidently good values – who doesn’t want to experience art or culture that is great and groundbreaking? As a result, the values themselves tend not to have been the target of criticism, just their application.

In practice, ‘excellence’ is not nearly as nimble a criterion as it ought to be. Instead of reflecting the best of the best in all its variance, excellence as an evaluative framework has congealed around a set of meanings: major institutions, high production values, established canons, heritage arts and so on. The net result, says Eltham, is that ‘the current funding paradigm favours the dead, the white and the male over the living, the not-white and the female. It favours the old over the new.’

But the issues run deeper than that. Excellence, at least in its current use, is difficult to reconcile with a lot of feminist creative practice. Whether by choice or necessity, feminist art- and culture-making has, for the best part of a century, embraced collective organising, DIY-production practices, transgressive values and an anti-establishment ethos. You can chart this approach across collaborative theatre practices of the early 1900s in Europe and North America, to women’s film co-ops of the 1970s and 1980s, the art activism of groups like Guerrilla Girls, Pussy Riot and Sydney’s the Kingpins, and punk-inflected DIY music scenes like no wave, riot grrrl and the Melbourne-based LISTEN collective.

This is a generalisation, of course, but across dozens of revisionist histories of women’s creative practice too numerous and too niche to detail here, there are examples of important figures and movements who have otherwise been sidelined because their amateur and/or collective methodologies, lo-fi aesthetics and non-commercial attitudes do not exhibit the necessary ‘high-production’ values, institutional compliance, individualism and ‘exceptionalism’ that befits the prevailing definitions of artistic ‘excellence’. In other words, excellence is the latest manifestation of a well-established aesthetic hierarchy that implicitly privileges certain forms, materials and processes over others on the basis of real or imagined gender (and often also class and race) associations.

In another recent Platform Paper, After the Creative Industries, Justin O’Connor offers a comprehensive critique of ‘creative industries’. O’Connor explains how in the 1990s, inspired by New Labour policies in the UK, government support for culture was cast off in favour of ‘creativity’, which was viewed as an exciting new kind of resource, one that governments would invest in rather than fund. According to this new logic, creativity is nimble, cool, entrepreneurial, innovative and, above all, a significant economic force (demonstrated recently by Arts Victoria’s rebranding as Creative Victoria and its new emphasis on the economic potential of the state’s ‘creative industries agencies’).

In service of this claim, figures were trotted out as proof of just how much the creative industries were contributing to the economic bottom line. But those figures now included a wide range of commercial services that stretched the definition of ‘arts and culture’ to incorporate advertising, hospitality, tourism, architecture and, most troublingly, software developers and digital start-ups. Creativity now seemed less about writing novels, making movies or taking care of an artist-run space and much more about entrepreneurial activity in the tech industries. Eventually, some creative industries advocates went so far as to exclude non-commercial pursuits (which in Australia means just about every kind of art and most kinds of culture) from the definition of the word; creativity was now a process or set of skills applied to commercial ends. ‘The desire to prove that creativity was economically valuable,’ says O’Connor, ‘succeeded at the cost of making culture disappear’.

There has now been substantial academic research into the professional lives of twenty-first-century cultural workers (though far too little of it has focused on matters of race, gender and class). Although this research draws various conclusions, the overall picture is consistent: chronic income insecurity in the form of freelance gigs, short-term contracts, ‘bulimic’ work patterns, unpredictable hours and the obliteration of work/life balance. While the gig economy is now prevalent in most sectors, it is particularly pernicious in the cultural industries, which have long been beholden to the romance of labouring ‘for the love of it’.

According to UK academic Rosalind Gill, the creative industries rubric, in combination with changing economic and political conditions, has helped to produce an entirely new labouring subjectivity. What is particularly interesting, says Gill, is how often this new subject – the ideal worker for the new economy – is hailed as female in management texts; she is social, flexible, adaptable, a good multi-tasker. Cultural critic Angela McRobbie touted the emergence of this paradoxical figure a decade ago. Championed as a ‘metaphor for social change’, the high-achieving, independent and ambitious young woman became the ideal of ‘female individualisation’. All this despite the immediately obvious problem that, as Gill writes, ‘in its injunctions never to be ill, never to be pregnant, and never to need time off to care for one’s self or others, it may pose particular challenges for women’.

With their emphasis on individualism, entrepreneurialism, agility, flexibility, constant reinvention and radical career uncertainty to the point of, as Gill says, ‘the impossibility of imagining one’s own future’, the creative industries of today present very pointy problems for women. But women creatives have been making similar claims about their working conditions for decades (given that, historically, women’s paid work was tied to their marital and maternal status, insecurity is perhaps the defining characteristic of women’s employment). The obstacles that once acutely affected women have intensified and expanded to such a level they now routinely affect the creative and cultural sectors as a whole. Or, to put it another way, industries that have historically been bad for women have gotten much worse.

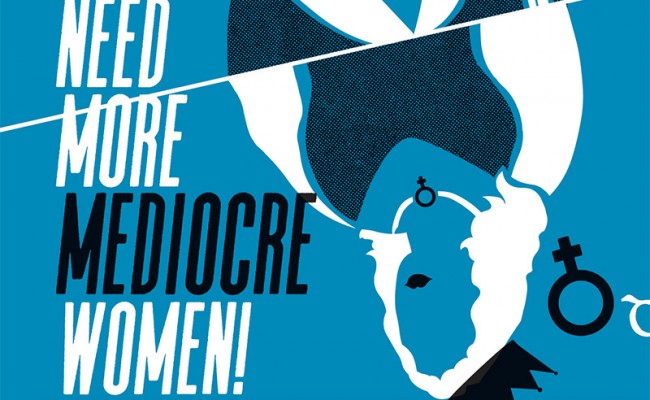

‘We need more mediocre women!’ That was the call to action issued tongue-not-entirely-in-cheek at last year’s LISTEN conference. The feminist collective aims to improve the profile and experience of women in Australian music. It emerged in 2014 following a Facebook post by Melbourne musician Evelyn Morris, in which she complained about the treatment of women musicians in Jimi Kritzler’s Noise in My Head, a history of the ‘ugly Australian underground’. ‘I’m gonna publish a book called tastes of Melbourne women underground,’ Morris wrote, ‘So tired of male back-patting and exclusion of anything vaguely “feminine” in subculture.’

At the second LISTEN conference in October 2016, panellist Samira Farah, co-founder of African arts collective Still Nomads and presenter with Sydney community radio station FBi, described her efforts to proactively book and program women artists, efforts continually thwarted by an apparent lack of confidence on the part of women musicians. Far fewer women approached her with press releases or demos, and as a result her playlist and email inbox were full to the brim with very, very ordinary men. What we need instead, the panel agreed, was more mediocre women.

It was a throwaway line, played for laughs not for keeps, but it does help articulate some of the biggest challenges facing any formal efforts to close the gender gap in a sector that remains totally beholden to myths of egalitarian meritocracy and entrepreneurial go-getting. It was a brief acknowledgement of a simple feminist truth that is still unwelcome (at times unspeakable) in the cultural industries: that men dominate creative scenes in a large part because they are men.

The persistence of those myths is troubling on many levels. In terms of gender equity, ideals of meritocracy and egalitarianism transform the obstacles women face into a problem of lack; the emphasis is always placed on what is supposedly missing from women’s skillsets. Women lack excellence. Women lack ambition. Women lack dedication. Women lack capacity. It may be couched in the politesse of policy – women aren’t enabled to fulfil their potential because of career interruptions, caring responsibilities, a lack of confidence, a reluctance to lean in and so on – but same fucking same.

As a result, official responses to the cultural gender gap have, time and time again, drifted towards a predictable set of strategies: a series of well-intentioned, policy-friendly interventions that don’t – and actually can’t – address more pervasive and damaging forms of systemic sexism. Indeed, the word ‘sexism’ is routinely abandoned in favour of ‘bias’ and ‘inequality’. The continued focus on maternity and caring responsibilities has become a too-easy explanation for the under-representation of women in the creative workforce. Important as motherhood is, it risks obscuring other much more significant (and sometimes much more difficult to acknowledge) sources of inequality.

Consider again the initial complaint that Morris made, which sparked the development of LISTEN and the Music Victoria report. It had nothing to do with childcare, mentorship opportunities or business development skills. Rather, it was a criticism of the marginalisation of women from the genealogy of local scenes, the masculinisation of the history of Australian underground music and, with it, the wider Australian music canon.

In an interview with RMIT academic Catherine Strong, Morris explained that this ‘impossible-to-put-my-finger-on lack of power’ results in a kind of creative gaslighting. Am I not as good as I think I am? Is my work not as important as I think it is? Self-doubt is a human condition, but a healthy ego is a necessity for a successful artist. While winning a funded internship opportunity or professional development grant can offer a confidence boost (good for a creative career in the short term), such initiatives cannot possibly overcome the erosion of self-assurance or ambition that comes from a fundamental hostility towards women artists and a trivialisation of their contribution to culture. That is the real source of the so-called ‘confidence gap’ that bedevils so many women artists.

Since sexist paradigms dominate official policy, the most useful responses have come from grassroots and activist spaces. Initiatives like the Stella Prize, its Stella Count and the Countess Report have helped reframe the conversation by considering gender inequality not as a problem of capacity, commitment or participation, but a problem of recognition for what women authors and visual artists are already doing. Meanwhile, LISTEN’s work on developing protocols for tackling sexual assault and harassment in live music venues draws attention to a serious issue routinely lacking from current cultural policy. Given recent discussions about Harvey Weinstein and Hollywood rape culture, it’s worth noting that although earlier reports regularly mention the problem of sexual harassment in the Australian film industry (25 per cent of respondents to a 1987 AFC report had experienced sexual harassment at work), the topic was nowhere to be found in the 2015 Gender Matters report.

The great paradox of contemporary cultural and creative industries is that while they exhibit ever-growing inequity across gender, class and ethnic lines, they are simultaneously characterised by an ethos of egalitarianism and meritocracy. As Gill argues, the all-powerful myth of meritocracy is ‘being used to repudiate claims of sexism’ when it is precisely, and paradoxically, the structure that produces it. Nowhere is this better expressed than in the recurring claims of gender-blindness. As McRobbie opined in 2004, one of the key characteristics of the feminist success story we see represented everywhere – the individual and agentic young woman freed from the constraints of conventional gender roles – is the displacement of feminism as a political movement. The myth of social and cultural equity, according to McRobbie, was advanced at the cost of ‘feminism as a political movement’.

The spectre of mediocrity haunts any explicit attempts to close Australia’s cultural gender gap. Policymakers, critics, audiences and a good many artists still worry that the inevitable price we would pay for greater equality is the value (economic and cultural) of the art itself. Or that, in pursuit of a numbers game of proportional representation, we will lose sight of the art (and indeed of more nuanced critiques of power and politics in the cultural industries). But if the rapid emergence and sustained impact of the LISTEN collective or the Stella Prize has taught us anything, it’s that feminist critique is more relevant and necessary than ever to comprehend the wilier forms of entrenched sexism in the contemporary arts and cultural sectors, and to move beyond the explanations that we all have grown much too comfortable with.

Read the rest of Overland 229

If you enjoyed this essay, buy the issue