‘They said it was in the woods.’

‘Where are the woods?’

Leni has come to visit. She answered my call. She looks around my room as though she is wondering if she is in the right place, even though I am here. The rooms and the corridors all have the same dark seaweed-green carpet. Lowest of low piles, scratchy on bare skin. With all the rooms and all the floors there must be acres of it.

My room has a lockable cupboard, for which I do not have the key. A single bed, a built-in dresser. To use it as a desk, I would need to sweep aside my brush and elastic ties and an accumulation of fallen hairs and dust.

Last night the boys came, their knuckles loud on the door.

‘What did they want?’ asks Leni, pushing up the bridge of her glasses. She used a fabric plaster to mend the frame. Now it is curling at the edges, begrimed and trapping strands of her mousey hair.

‘I don’t know. I didn’t open it.’

‘So how do you know it was the boys?’

‘Who else would it have been?’

Actually it was the way they knocked. I heard sniggering, or if it wasn’t sniggering, some kind of breath-grunt-muttering. There were two of them. I got into bed. I held onto the sheet.

They banged three times. No-one bangs on the door like that if they mean well. No-one tries the door handle if they want to make conversation.

I held onto the sheet and worried, not for the first time, about who had the key to my cupboard.

Later, having crept down to the safety of the common room, I eavesdropped past the blare and bellowing of the TV, where a group of them had gathered. Surf hair, gawky limbs and crests of laughter.

‘It’ll burn you,’ shouted Surf Hair, over the ads. ‘I’m fucken serious mate.’

‘I’m not going near that shit,’ said Gawky Limbs. ‘I’ll run a fucken mile.’

‘So yeah,’ I say to Leni, in my room.

‘Which woods were they talking about?’ says Leni.

‘I don’t know,’ I say. It seems to me like a pointless question.

‘What would you do with it?’

I nod to the cupboard. Leni tries the handle and I say, quickly, ‘I mean if we can find the woods in the first place, and then get it back here, breaking the lock will hardly even seem like a challenge.’ I feel out of breath just saying it.

Leni tries the handle again. ‘But it does now? Feel like a challenge?’

‘Yep. It does now.’

She puts her bony hands in the pockets of her grey jacket. Then she half nods, half shrugs. It’s like her left shoulder is asking the question. ‘What if it’s too big to fit in there?’

‘Leni, you have no faith.’

She sighs.

Leni says that first we have to go and get B. This is what we have to do if I want Leni to come, so we wait for the bus, and I feel the way I always feel, which is having only two things to choose between, and neither of them what I really want. The sun squints at me through a scrunch of clouds. On the pavement sits a shiny dog turd, neat as a sausage.

On the bus, Leni takes the seat in front of me and puts in her headphones.

The bus yawns and rolls. It is no vehicle for a quest. It loiters outside a shopping centre, the engine dull. The thread of Leni’s music needles me; it’s like I’m hearing it through a sieve. Stars the colour of liverwurst are painted on the supermarket window. Inside them, specials. Toilet duck. Forequarter chops. Batteries. I think of the woods growing dark. I fidget in my seat and worry that the bus will never leave.

But it does. On the block next to B’s unit, an excavator tears at a vacant house with its metal teeth. They are called teeth. It’s not a metaphor. No-one has taken the window dressings down. Here is a dangling venetian blind, white and warped. A long tail of netting. The truck out front wears an ‘I Love Scrap’ sticker. Who sorts gladly through that mess of splinters and rubble?

B comes outside, black ponytail swinging.

‘How did you know we were here?’ I ask.

B looks at me as though my question does not make sense.

I think this means we will not have to go inside B’s unit, but I am wrong.

Leni follows B across the bitumen, past the other units, and I follow Leni. B opens her front door. Music is playing on the stereo. It is dark inside and the music sounds dark to me, hollow with grief. The grief is for something buried under the layers of its own making, the means of its transmission. It’s too loud for talking and B moves through the lounge like we should know what she is doing, how long she is going to take. I worry we are not going to make it. It’s dingy everywhere, yet here I am, here I have been brought as if this is a place I might want to be. The vertical blinds are closed and their broken chain trails on the lino. There are two enormous armchairs, padded recliners, dirty blue.

Cat litter in the kitchen needs changing. Mugs on the tree, powdery with old grime. I rinse one under the tap as best I can. In the next room a budgerigar chirps and scrabbles in its cage.

There is always the sense of someone else here, but I never see them.

The water tastes of chlorine. Leni explains to B about the woods. She leaves out the part about the boys.

‘We’re on a quest,’ I say, hoping to put B off.

She shakes her head. ‘A quest is, like, Frodo and Samwise going to throw the Ring into Mount Doom.’

She thinks she’s corrected me. There’s no point in answering. When she silences the stereo, the noise of the excavator grinds through the room.

Leni lives furthest, so we go to her house last. The yard is worm-wet, leaking chlorophyll light. Broad thick leaves of dock and thistle, growing dense like they mean something by it. It’s always winter at Leni’s. The light diluted. You can’t see the woods yet. There are empty blocks, overgrown and junked with rust and blown plastic, that might be mistaken for fields. There is a stormwater drain where she and I used to dare each other. Go in. Go in the furthest. It got dark and bent away. I felt it then, the dark cold jolt of my own fear, lodging itself in my chest for good. In my heart, heavy as an anvil, cooling the blood that pumped over it. No dare could override that, not any more.

Leni sleeps in the caravan. The caravan is almost part of the yard. I don’t know if it still has tyres, or if they’ve shredded away into the earth. When you lie inside on Leni’s bed, nubbly foam with sheets that are always crumpled, always cold, you can feel the chill from outside on the window, under your fingertips. The grey seal around it puckering, disintegrating, letting in damp and whispers of air. It’s just a metal box that keeps out rain. Keeps you arm’s length from the yard’s devouring greenery.

Both girls turn to me now, as if I have brought them here on false pretences.

‘Where to?’

I have been following Leni. I have not thought any further than this. I take out my phone and search for green places on the map. You can’t tell from a green shape on a map how many trees will be there. But there is a direction from Leni’s place in which the grid of roads appears to thin, and the beige of blocks and buildings gives way to meandering green edges.

‘That way,’ I say.

‘How far do you think it is?’ asks Leni.

‘Yeah, how far is it?’ says B, but with her it is more like an accusation.

I want to say, if you think it is a stupid idea, then don’t come. No-one asked you to be here. But Leni did, Leni asked her to be here.

And I don’t know how far it is. That is not the kind of thing I worry about. I only worry about whether I am going towards it, or away.

‘Have faith,’ I reply, and turn to lead the walking.

‘Have fucking faith?’

Leni doesn’t say anything. She would have taken my side, once.

B won’t make it, I think to myself as we leave the grass for the footpath. Our feet, mine and Leni’s, are in sneakers, and B’s are in soft boots of seamless suede. She cannot follow me for long enough. She will miss her cat, or something else stupid, and turn for home.

‘What does it look like, anyway?’ asks B, as though we are nearly there, and need to keep an eye out.

‘Like the sun.’ I say it quick. ‘The setting sun – red like that.’

‘Blood red,’ says B.

‘No. Golden red.’

B must have seen the sun set fewer times than me.

We make distance, leaving numbered houses behind for an arterial road. We range along the shoulder, our feet scuffing off-beat in the gravel. The wind comes off the abattoir and buffets us like laundry. Swift traffic hisses and roars. The fields are more like fields now but they are not the green bits on the map and nor are they green in real life, they are piss-yellow, dry and grey, there is barbed wire sometimes and the occasional lonely warehouse. I see a sleeping excavator with its mouth closed. No matter how much road we walk there is more of it, and I cannot see the woods.

But the map says the woods are this way, and I keep walking.

The wind is making me cold. Leni has tied her jacket around her waist.

‘Can I wear that?’ I ask, and am stung when she says, ‘No.’

B has been walking through the gravel, frowning at her soft boots. She stops and watches us both.

‘But you’re not wearing it, and I haven’t got a jacket.’

‘You do, actually,’ says Leni. There is a thin sharp edge in her voice. ‘You just didn’t think to bring it.’

She walks off again, slowly, and B follows. A truck full of cattle careens behind me and away. The animals are going to die. At least they don’t know about it.

I start walking, following now, which doesn’t feel right. The one with faith should lead the way. And I’m thirsty. Leni will have water in her bag, but I’m not going to ask. She will need a drink soon, though. She will have to offer me some.

Unless she drank when she was behind me, sharing the bottle with B.

It doesn’t matter who leads the way to the woods, I tell myself. It’s better to hang back, and keep an eye on them both.

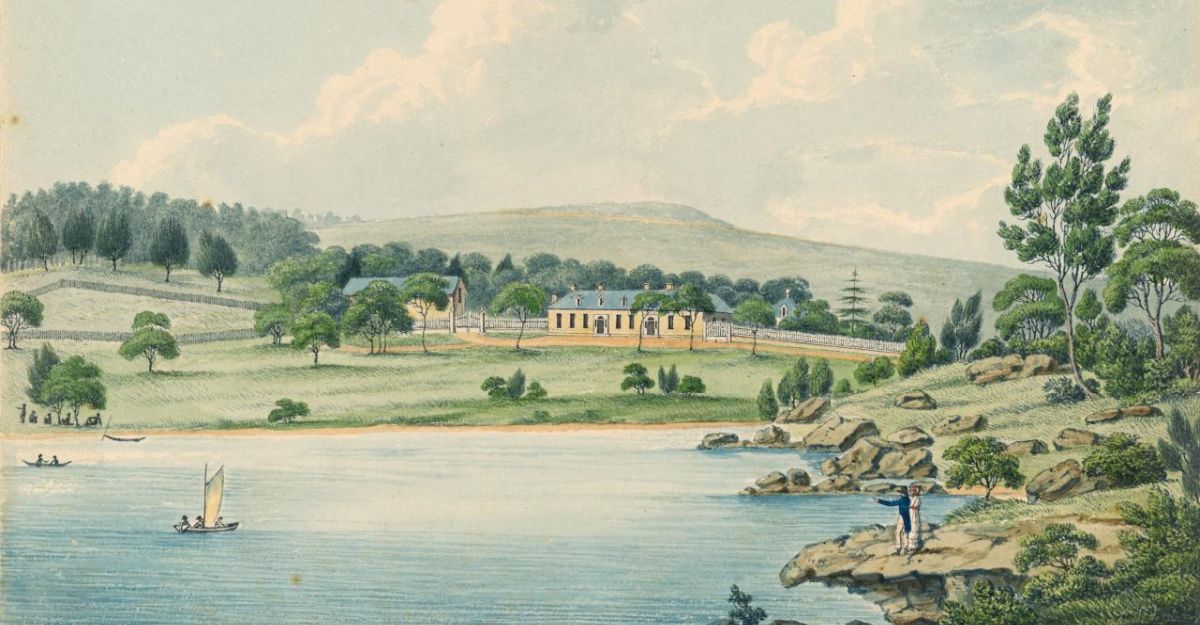

When we get to the woods, it will be dark and cool, but not at first. At first there will be a slope, gentle then getting steeper, and the sun will be out. It will be like a meadow that we want to lie down in, among tiny pea-green creepers and star-petalled flowers, and doze under blissful eyelids glowing red with the sun behind them. But we will pull each other to our feet and make our way upwards to where the ground cover grows deeper and springy, up to our knees almost, and then an opening in the trees will welcome us like the arched doors of a church, like somewhere that has been waiting for us our whole lives. When we go inside it will be like a room, a loamy twilight vault, vast and hidden and safe.

When we get to the woods they will thank me. But for now the road is flat. The so-called fields are flat. Up ahead there are two, maybe three houses and a service station.

B forgets her feet and hurries ahead. Leni throws one look back at me, and for a moment I think she is going to wait.

They are already inside when the sliding door admits me into the shop. Outside there are trucks in a lay-by; in here, shelves of snacks in wrappers, a rack of Tic Tacs, refrigerated drinks. I rub coins between my fingers, in my pocket. After the bus I only have seventy or eighty cents. It is not enough to buy water. It is only enough to buy a Curly Wurly or a Milky Way. The man behind the counter has a short white beard and wears a polo shirt. His skin is red. I can picture him on a boat. As I pay for the chocolate, I ask him, ‘Excuse me, do you know how long it will take to walk from here to the woods?’

I am very polite and also quiet because Leni and B are looking at the flavoured milk in the cabinet on the other side of the shop. But the man laughs and says, ‘The woods!’ in a voice loud enough to be heard by anyone.

Then he looks at me the way people look at very young children. But he doesn’t answer my question.

B has bought caramel milk for Leni. She didn’t buy anything for me, and Leni won’t need to bring her water out now. We walk past the silent trucks and I offer each of them a bite of my chocolate bar in the hope that they will offer me a drink in return. Leni shakes her head, her lips around the straw. B doesn’t even answer.

It is afternoon and the clouds dissipate for the declining sun. We walk into its weak glare. Leni and B discard their milk cartons in the gravel. It is hard to see into the distance.

Something rises out of the flatness.

It is in the road, dinosaur-sized. We stop talking and I sense more purpose in all of our footsteps. We walk towards it, minutes upon minutes, until we can see that it is an overpass, until it sits above us, a close horizon, drenched in watercolour sun. Two pylons, a heavy bridge, hillocks of dirt on either side to lift the road.

B stops. She has the stance of someone who has been waiting for her moment to stop, someone who has reached a boundary. She says, ‘if we’re not even there yet, how are we going to find what we’re looking for and get back home before dark?’ She rolls her tongue around inside her mouth as though she has said something very satisfying. ‘I am not spending the night in the woods,’ she declares.

Leni nods, slowly, as though B has just spouted some kind of fact. She says to me, ‘I think we’ve come far enough.’

‘That is plainly false,’ I say, ‘since we are not there yet.’

Leni sighs, and shifts the straps of her backpack. ‘We gave it a good shot,’ she says. ‘It’s time to go home.’

‘How is this a good shot,’ I shout, even though I don’t mean to, ‘when the woods are nowhere in sight!’

‘Exactly!’ shouts B. ‘The woods are nowhere in sight! You don’t even know how far away they are!’

The thing is, I don’t know how far away the woods are and I never said I did. The woods could be far, far away, like hundreds of kilometres, and I have known this all along. If you let people pin you down to the details then they’ll tell you something can’t be done. The point is, if we walk for long enough we will get to the woods eventually, and that is all I need to know. It used to be enough for Leni, too. To be the one to remember the water and the warm clothes, and let me show her what is possible.

My face is dusty and the tears are making it worse.

I take out my phone and locate us on the map. Beyond the overpass is the beginning of those green edges and shapes, the dwindling of the world we know and the beginning of the one we are looking for.

‘Come up,’ I say, pointing to the overpass, ‘I’ll show you where we’re going.’

B starts to speak and I see Leni give her a look.

I see it all, suddenly: Leni lying back on a padded blue recliner. And I feel some kind of sick heat inside me that’s good for nothing.

‘There’ll be a view,’ I croak.

Leni’s footsteps follow mine, sinking in the loose dirt of the rise. B is sitting in the gravel, right where she stopped. The structure seems bigger now that we are climbing it and this is fortunate, I think, the higher the better. For while there will be a view, I don’t know what the view will be of. I don’t know if it will be enough.

On the bridge there are four lanes for traffic but no emergency lane, just a gutter of concrete along the barrier, wide enough for us to walk in. We cross the lanes and stop in the centre of the overpass, looking at the future of the road we have been travelling, its endless grey geometry.

The land on either side continues flat. There are no buildings.

There are no trees.

Leni gives me water in an empty Coke bottle. It tastes plastic, sweet.

‘Listen to me,’ she says, ‘listen. What are you looking for?’ I hear exasperation in her voice, and I know she is not asking so much as trying to remind me.

I lower my eyes from the horizon to the road below. What I’m looking for is not something that can be explained or described or even pointed to in the distance or on a map, and Leni knew that once.

She takes off her jacket and makes a cave of it over my head. And in the false darkness she takes my wrist roughly, like it is something disconnected, and splays my hand over the screen of my phone.

‘There,’ she says, as though there can be no argument, and I look. What does she think I will see? It is just light, radiating up through the skin and muscle of my fingers, like a red sun.

Read the rest of Overland 226

If you enjoyed this story, buy the issue