The Victorian government’s Royal Commission into Family Violence is currently under way, but no-one who works in the sector is expecting it to produce any new insights. ‘Domestic and family violence’ is, overwhelmingly, violence against women and children by men.

At the often moving and bitingly reflective blog Ginger and Honey, Stephanie Convery writes:

My gloved hands lumbered against the pages of that old novel about men and their over-confidence in ideas, men and their hasty, unrequited loves, men and their wars with each other and the (female) casualties they sustained as they blustered their way towards meaning. Is it power? Is it sex? Is it an idea made bloody – manifest across an unwilling world? Did any of those men really understand love at all, as they grappled over the possession of people they had no right to claim?

The answer, of course, is no. And we still don’t. Nobody would write as much about love as men do if they weren’t trying to hide their fear of it. Inhabiting contemporary masculinity is a continual invitation to collude with misogyny, violence and emotional stupidity.

Literature – which has mostly been policed and sanctioned by men – talks about love at great length, but has adroitly avoided the topic of male violence. Violence is usually the result of impersonal forces or evil geniuses, a metaphysical mystery, an expression of the dark side of the human heart and so on.

Last year, David Cunliffe, former leader of the New Zealand Labour Party, spoke at a women’s refuge symposium: ‘I’m sorry for being a man,’ he said, ‘because family and sexual violence is overwhelmingly perpetrated by men.’ It was an unusual statement that I want to problematise a little.

Cunliffe was immediately ridiculed by New Zealand’s Prime Minister, the profoundly strange John Key (who, it was recently revealed, continued to harass a young woman who worked at a cafe he frequented, despite being repeatedly asked to stop). Key said that domestic violence is the problem of a few men. It’s a common argument: most men don’t need to change. Apart from a few deviants, the brotherhood is good.

Key is a man utterly unwilling to acknowledge his own abusive behaviour, but Cunliffe hasn’t really taken responsibility either.

It’s important to experience some shame in looking at one’s own masculine privilege, but wallowing in it evades responsibility and asks others – that is, women – to do the emotional work of validating you yet again.

And while women’s experiences are often impenetrable to men – not because women are mystically moody, but because men live inside a bubble of privilege and entitlement – men’s experiences are not impenetrable to other men. Yet we rarely talk about or question our experiences.

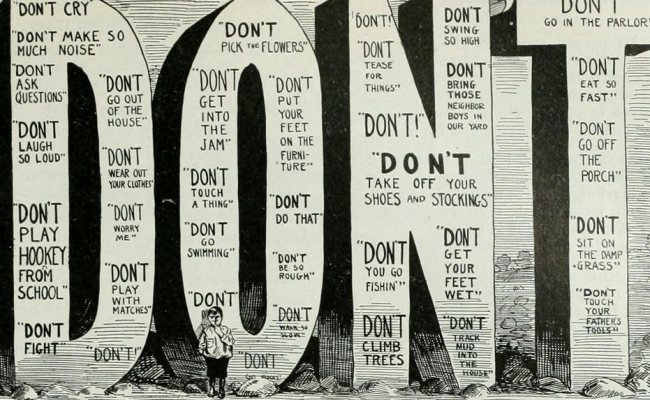

Contemporary masculinity invites men to be narcissistically dependent on, yet simultaneously frightened of, women. We do little, if any, real emotional labour, leaving this for women and children. When they need us to do a little – or don’t give us continual reassurance that our avoidance is praiseworthy – they are charged with deliberately wounding us. We become so panic-stricken that we attempt to control them in increasingly minute ways, while we ourselves go to pieces psychologically. I think these are general characteristics of masculinity under consumer capitalism, a system that supports and nourishes those characteristics. Men murder and abuse to solve a problem within themselves.

In 1992, Paul Keating gave his famous Redfern Park Speech, in which he spoke on behalf of non-Aboriginal Australians and took responsibility for white violence. Though I have many problems with Keating’s incumbency, it’s hard to gainsay the significance of this speech.

If a non-Aboriginal prime minister can take responsibility on behalf of non-Aboriginal Australians for the treatment of Aboriginal people, then a male prime minister can also take responsibility on behalf of Australian men for the abuse and murder of women and children by men, as well as for the entrenched inequities and attempts at humiliation that women routinely face. Keating’s speech could be a good model if that imaginary prime minister feels a bit stuck:

The starting point in addressing violence against women and children, and other men might be to recognise that the problem starts with us men.

It begins, I think, with that act of recognition.

Recognition that it is we who are responsible for the violence and abuse.

We destroy the homes, the hopes and the promises.

We commit the murders.

We divide the children from their mothers.

We practise discrimination and exclusion because of our ignorance and our prejudice, and our sense of entitlement.

Down the years, there has been no shortage of guilt, but it has not produced the responses we need. Guilt is not a very constructive emotion.

Patriarchy and capitalism go together like Bush and Rumsfeld, or beer and vomit. It’s a collusion whose effects are abuse, murder and rape on an epidemic scale. As Ntozake Shange put it in her poem ‘Some men’:

some men

would rather see us dead than imagine

what we think of them