An affirmation of Overland’s sixty-year commitment to progressive culture, the prize nurtures the emergence and enlargement of poetry in the world, and in so doing fosters poetry’s custodianship of the ecologies of life and meaning. As Judith Wright herself once expressed in an address to the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, ‘all these other concerns – conservation, Aboriginal rights, human rights, and the defence of freedom of speech – are as important to me as poetry, and indeed indispensable to the writing of poetry itself.’

This year the prize attracted over 500 entries. I spent many weeks washing and peering through their murky alluvium, and eventually found in my hands twelve small nuggets that had fallen in a fine gold precipitate. The twelve shortlisted poets – Carolyn Burns, Zenobia Frost, Myles Gough, Banjo James, Caitlin Maling, Andrew McLeod, Mark Mordue, Aden Rolfe, Gareth Thomas, Andrew Michael Watts, Connor Weightman and Mitchell Welch – have each refined tremendous value from their experience of life in the poetic world.

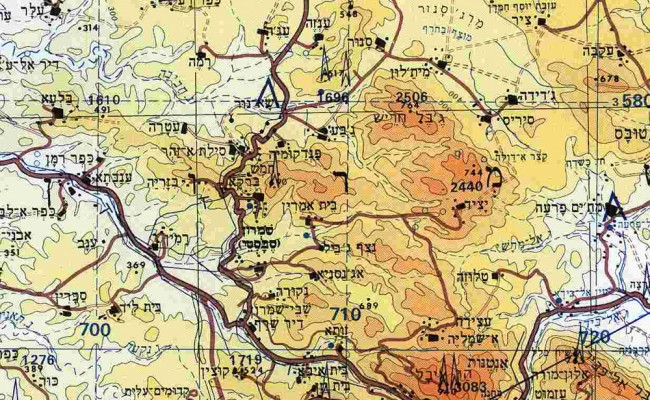

The winning poem, ‘topography’ by Myles Gough, is a very fine free-verse lyric that charts the recognition of place as a crucible for character and relation. Gough’s success is further testimony to how important the Overland Judith Wright Prize is in the development of new talent: his poem ‘The Watchmaker’s Wrath’ won third prize last year. Well done, Myles!

Gough is closely followed by second prize winner Andrew Watts, with ‘Lagrange’, and third prize winner Mitchell Welch, with ‘Stanwell Tops’.

This year’s winning and shortlisted poems are all sustained by a noble attention to poetic language and perception. You might ask – indeed, I am often asked – how one can possibly judge or distinguish the ‘quality’ of a poem, especially a poem written by a young poet whose work is largely untried and vulnerable. An answer can be found in the economy of the line and how distinctly it synthesises experience, feeling and thought. If the winning poem is read closely, each line can be seen as a well-defined unit expressing a discrete observation:

the jagged cliff is bird-like. Eagle rock, says the map

I say it looks more like a turtle’s head

protruding from an ancient sedimentary shell

you’re wrong, she says, tracing an outline with her finger

nail painted purple. It’s definitely an eagle

down below, turbulent waves crash and spill over the flat shelf

white cold and bubbling

This kind of fidelity to the relation between poetic language and experience, found even in poems that might be considered innovative or experimental, is a hallmark of ‘quality’. Every line embodies perception, ideation and the breath. This is an implicitly political procedure, as the faithfulness of poetic language to the world depends on its character or ethos, its nature and temper. The face of the universe, its topography, can be seen and traced with a finger, a line, a word, as illustrated by Gough: ‘I know, she says, I know’. When so much in the workaday world is aimed at making us lose attention or forget, to know poetically is to give proof of what endures in the world around us.

Please join me in congratulating the winning poets.