Day 1: Aljazhab.

The oldest city in the world seems a likely place to find ghosts. The cab plunges into a hot, dusty turmoil of traffic, crowds and distorted calls to midday prayer. After the sensory deficit of the five-hour flight (barely diminished by Raangela and flirting with the Swedish air hostess) the city wakens me with a slap in the face. The smells stream inside: rose tobacco, rank sewage, spicy charred lamb from the street stands. The light has a peculiar quality in this part of the world; it crystallises in the torpid mist of exhaust vapours and sand, making the world at once dream-like and more real.

The outskirts of Aljazhab conserve that drabness that would have been called modern in the late 1970s, but the beauty of the city is gradually unveiled as we enter. The town is an incongruent palimpsest of materials and styles in which asphalt mixes with glazed mosaic, plaster with stone, stucco with plastic. The advertising signs appear to have been time-tunnelled from another era – and so, it seems, have I. It’s been twelve years since I was last here and the place remains as I remember it, or as I believe I remember it. There is an initial sense of displacement, as though I had just been dumped into an elaborate reconstruction of one of my memories.

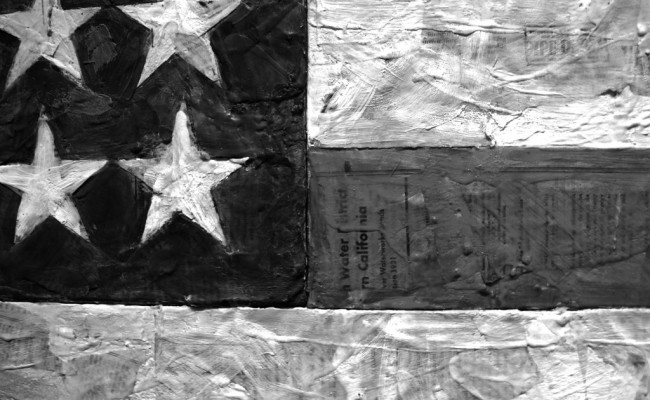

Amorites, Hittites, Akkadians, Phoenicians, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Crusaders, Ottomans … The United States of America is the last in a long rollcall of infamous empires that have taken turns to rule this place during the last 8000 years. The French seized it, briefly, in the early twentieth century, before the series of bloody uprisings that led to the creation of the modern state of Qiram. At the peak of their powers, each of these empires must have seemed invincible and eternal, but now look at them: their remains are barely decipherable in the scatter of eroded architectural motifs. I’m certain that the ghosts of the Americans will eventually drown in the din of this primeval, overpopulated netherworld. But can the undead die a second death?

My Arabic is rusty and Yassar, the driver, plasters the gaps in our conversation with spurts of English. He leaves the taxi to drive itself while punctuating his comments with vehement movements of his hands. As the walls of the ancient citadel loom into view, the difference between the road and the sidewalk, shaky at best, vanishes altogether. The driver curses at a cluster of Suzuki vans stuck in a narrow intersection in front of us; these comical relics, now fitted with electric engines, are popular for being cheap and also small enough to negotiate the narrow maze of backstreets in the old town. We slow down to a human pace and his gaze hovers on the rear-view mirror. He asks me what I’m doing in Aljazhab and I answer as honestly as I can. He nods to himself and for a moment he appears to be stifling laughter, but then he turns serious: ‘Go to the main square, my friend. Go to the central bus station. You’ll see the real ghosts there. Children burned with the chemical weapons, grandmothers without legs, everyone is begging and dying.’

The unmanned wheel shudders as we rush through a gap in the chaos. He’s making me inexplicably nervous.

‘I’m curious.’ I feel I have to prove something, justify my visit. Perhaps I have to prove I’m not American: that awkward, familiar feeling that non-American English speakers often get overseas. ‘I’m a journalist; it’s my profession. See, I was working for Associated Press last time, covering the last days of the invasion. And I was one of the few to openly call it that – invasion – although that bit was mostly edited out.’

But Yassar has lost all interest. When we arrive at the hotel he glances at my twenty-sheikh note against the dusty light from the windscreen and quickly pockets it. I’m fresh from the plane, after all. ‘May Allah give you plenty of children.’

Too late for that, my friend.

Day 3, I think, and here I am writing from the old Sheraton.

Khaled is late, says he’ll be here tomorrow evening. Which is fine, since my feeling of displacement has not worn off yet. Yes, what am I doing here?

I have walked around the edge of the moat of the ancient citadel but been too anxious to go in. It seems that the desecration of history can make me angrier than the killing of thousands of people. The historical heart has been carefully reconstructed and the new brickwork melds seamlessly with the old materials, but I know that most of it is fake. I see everywhere the same desire to patch things up and to leave the past behind. Glorifying the ancient past is one of President Ahmed al-Zhara’s main strategies for facing the future. The Sheraton has been renamed Mehmunkhuneh Qasr, which means ‘Hotel Castle’, in reference to the nearby medieval ruins. This was my home for nearly a year; now it’s hardly recognisable. The whole place has been wallpapered anew with filigreed Arabic patterns in gold, turquoise and brown. Photos of al-Zhara are prominent in the lobby and reception area, and I see his smiling, waving portrait everywhere in the city. A Sunni Muslim, like the majority of Qiram’s population, al-Zhara managed to trade his status as poster boy of al-Qaeda’s anti-US resistance for political profit. He is now going for more, building himself into a beacon of pan-Arabic unity in a region of shaky democracies, fragile peace deals, constant bursts of civil war, and a mosaic of ancient and seemingly irreconcilable ethnicities and faiths. The American collapse and the near annihilation of Israel has not brought any visible improvement to the welfare of the average Arab or Persian citizen; but it is early days yet, so everyone says. Al-Zhara’s family owns a construction company that was granted most of the contracts during the post-war reconstruction. On the bright side, he has managed to wean the economy from its dependence on oil and steer it towards the production of renewable energies. An example for the region, it is said – although the truth is more complicated, of course.

The concierges wear dark suits and chequered keffiyehs, and have the acquiescent, cheerful manners of air stewards. This is one of the few places in the city where alcohol is legally obtainable. I remember the feverish atmosphere during the time of the transition, the swarm of journalists and officials, the abrupt outbursts of violence. Sometimes (not often nowadays) I’m woken in the middle of the night by the sound of an explosion in my head. It takes me a whole hour to go back to sleep. Once, the insurgents managed to launch a bomb into a window on the first floor, killing five people. I’m not sure where the explosions in my head come from, whether they are from Assam, Kashmir or Tripoli. I had seen dead bodies before, but I had never seen them twitching like they did in Aljazhab. Like they wanted to get up and get away from there.

In the unconscious of the world, time heals nothing.

Day 5.

Last night Khaled finally arrived and watched me drink at the bar of the hotel. The beers are Japanese, the wine from Saudi Arabia, the whiskey from Ireland. Khaled is a British-educated doctor, born in Syria and now living in Baghdad. I first met him fifteen years ago, after the bombing of Tehran, when he worked for Al Jazeera. Some dark twists of fate made him become a reporter: most of his family was killed in Damascus and he felt he had a duty to record the American atrocities. He started off embedded as an army doctor on the side of the resistance. We spent six months working here together. Khaled has put on weight and grown a beard, but otherwise it seems like no time has passed. Family bonds grow between people in such circumstances. After a lengthy and effusive welcome, Khaled pelts me with questions: the Hague trials, the polar winter, the water shortage, the secessions in the US … But I tell him there is no more to know than what you see on the news. Besides, reality is so much more interesting when you have footage.

A freelance bum, he calls me. He pronounces it bom. ‘The whole world is the Third World now.’ He belly laughs as though he’s invented that cliché. His gaze narrows: ‘You’re blogging this, aren’t you? I’ve checked. Don’t mention I’ve put on weight.’ He glances furtively at the scars on my face and I lift my chin to show him the latest one, on my neck. He inspects it with a professional frown and shakes his head. ‘You white people chose the worst spots to colonise. You should have stayed in Europe. Really.’

‘And miss out on all that gold, cheap real estate and exotic two-headed women? We would do it all over again if we had to. Anyway, it worked quite well for you in the end. You fat Arabs are sitting at the top of the food chain now. Again.’

When the conversation begins to deflate we are left with no choice but to face the reason for our meeting. We’re both kind of embarrassed at first, although I have the advantage of being half drunk. We spread out what we have on the table. I have maps, mainly; he has photographs and reports. We compare facts and intel. The first sightings were reported six years ago in Iraq. Check. At first the Iraqis assumed US covert operations were being carried out in their country – which was ridiculous, of course. I heard the Iraqis sent reconnaissance missions. The UN team and the air surveys yielded nothing but a handful of blurry photographs that can be easily googled and which could be of anything. The reports continued to spread across Iran, Syria, Qiram and other former foci of the doomed US takeover. These shadowy figures have become part of the local folklore, adding to the already abundant stock of ghost stories in these parts. Apparently they can be seen only at dusk, during sandstorms or in heavy haze, and they appear and vanish suddenly, like mirages. Silent explosions can be seen flaring up in the night. Some people have claimed that, after sunset, they can hear the sounds of distant gunfire and of fighter jets flying overhead. In some villages, people are afraid to go out at night or to leave their children to play alone in the streets.

‘These are straight from the source.’ Khaled shows me a photo of what appears to be a human shadow advancing through a sandstorm: the shape of a soldier crowned by the distinct Advanced Combat Helmet. The image has been blown up and is grainy. ‘It’s a doozy … Is that what you Australians call it? It’s fair dinkum, this one.’ I make an effort to seem amused. ‘Whatever we do, we need to stay away from the border. Zionist terrorists are active all along the frontiers with Jordan, Israel and Lebanon. I can accompany you for three days. Then I have to go to my cousin’s wedding in Damascus, and you’re on your own for a week. Supposedly I have to go back to work then, but I’ll do my best to come back and check on you.’

‘I appreciate it.’

‘Just keep me out of the credits. That’s all I ask.’

‘This is just preliminary research. Won’t harm your reputation.’

‘You’ve sold out to this New Gonzo stuff now, no-one will believe you. Who is it now, The History Channel?’

‘I’ll know the buyer when I have the product.’

Khaled is flicking the corner of the photograph with his ring finger. His expression darkens. ‘I don’t doubt that these mirages are a product of the imagination, but why do they take just this shape? If this is some kind of weird way to cope with collective trauma, then we Arabs must be really masochistic.’

But the reports might have a source in fact. During the final stage of the American collapse, as the supplies dwindled and the command structure crumbled from Washington downwards, rogue bands of soldiers went AWOL and looted local villages and towns, raping and killing whoever stood in their way. These episodes have been added to the bottom of the long list of war crimes that American officials, including two ex-presidents, are answering for at The Hague. I tap my finger on a spot on the map: Umm Jebel, a former US base in the nomad routes. Khaled shrugs his shoulders. ‘Time for one last round?’ he says, pointing to my empty glass, reading my mind.

Day 6: Umm Jebel.

We set off into the desert at the first glimmer of dawn, narrowly missing prayer time. With its smart temperature management and silky hydrogen engine, Khaled’s 4WD is like a biosphere on wheels. Once we cut through the hills northwest of Aljazhab and hit the H1, we enter a flat, eerie, golden emptiness. It takes my mind a few long minutes to tune in and appreciate the eventfulness of this landscape. To a westerner’s mindset, the desert is an unforgiving nothingness. But to the people who live here, this place teems with information. Every sand dune is a sign and every mudflat a story. It’s obvious to me why the religions of the Book are the religions of the desert, cults of an angry Father who has withdrawn from sight and left his children to wander alone in a world without end. I’m careful not to share these thoughts with Khaled, although he would probably just laugh at my ignorance.

This highway has seen a lot of action: years of routine sabotaging, hijacking and bombings; yet it now looks fresh and perfectly smooth, another indication that post-war Qiram is good business if you know where to find it. Soon we are passing through a series of oases. It takes us five minutes to drive through the largest one. These patches of bright green vegetation dotted with clusters of palm trees are springing out everywhere; fertile areas that are locking in the moisture and slowly spreading. Khaled tells me that the rainy season has just started. I open the window and the gust of humid, almost tropical heat takes me by surprise. In another twenty years, this place will be unrecognisable.

Next, we drive past a sprawling wind farm, one of the largest in the region. It is set at some distance from the highway and accessible through a series of unmarked dirt tracks. We can just make out the tall, serene turbines sprouting from the landscape like a new, monstrous breed of flower. After two hours, we switch places and I take over the driving. We are both aware of the vague anxiety gathering around us. This is, after all, a place of voices and visions. The desert makes all those stories suddenly seem more plausible. The sun is climbing fast and we are now slicing through curtains of heat. A mirror of scorching air hangs at the vanishing point on the horizon, seemingly receding from us. I notice another difference since the last time I was here: flat, horizontal rainbows are forming in the humid air, like floating mirages.

We arrive at Umm Jebel by ten. This was once an archaeological site dating from the sixth century, but the Americans destroyed what little remained of it. Forward Operating Base Carson housed the 1st Infantry Division and the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment. It was a strategic resupply point between Aljazhab and the Syrian border. It housed a small airbase and was also the centre for highway security operations on the H1. Most of the major US bases have been looted to the last tent pole, and what remained has been dismantled as part of al-Zhara’s campaign of historical renewal. But some military emplacements have been overlooked or adapted to other purposes.

Following the instructions from the GPS, we turn sharply right into the sand and drive by blind faith, in near-zero visibility. Khaled taps me on the arm and snaps me out of a reverie. I take this as a sign to stop. Sure enough, the GPS shows our car standing on the destination icon.

As the sand clears, we find ourselves at the foot of a shallow artificial embankment. There’s movement ahead: people waving at us and hurrying towards the car. The children arrive first, dressed in striking many-coloured kaftans. Their vibrant, curious faces swarm around us as we get out of the vehicle. They feel the threads on the tires with their fingertips and pat approvingly the slick grey glazing of the chassis.

We climb the embankment. We are standing on an old runway almost wholly covered in sand and rocks. Concrete slabs mark the old perimeter, but the fence is gone. Camp Carson has been stripped down to its garters. Fences, doors, containers, bricks, poles – everything that could be moved has been plundered. We approach the nomads’ constructions that meld ingeniously with the derelict but still robust foundations and scaffolding. The rusty, sinking skeletons of two armoured vehicles flank the main entrance. The children are speaking all at once, a dialect I don’t understand. They flash us smiles. Khaled waves them away, but they press closer to us. For some reason, they find the whole situation hilarious. An old man is approaching, dressed in an impeccable white kaftan and keffiyeh, and carrying a long staff. He looks extraordinary agile for his age, and I infer he is the sheikh of the tribe. He offers a wide, three-toothed smile and his arms open slightly in welcome.

We are led through the camp, past barking dogs, more curious children, groups of women with embroidered scarves and indigo tattoos, a bonfire of tamarisk and willow, wandering goats, the smell of cardamom and roasting coffee. A group gradually accretes around us. The introductions and well-wishing are exhaustive. They’re speaking Arabic now, but I let Khaled do most of the talking. I’m amazed at how the nomads have taken advantage of the few remaining walls and structures. Wall coverings hang between steel beams and the concrete floors are dressed in goat-hair rugs. Having streamlined the ancient art of occupation, the Americans assembled their bases quickly out of prefab parts, and could erect long-term fortifications such as this one in a matter of days. The old barracks have been converted into a stable for donkeys and horses. I also notice two camels, a sign that the clan is doing well. Most of the living quarters have been set inside the two medium-sized aircraft hangars, which keep cool during the day and warm at night. We are invited to sit on a carpeted floor under an awning. Five of the men join us, plus the sheikh who follows our conversation in silence at first.

With our first coffee and dates, Khaled broaches the subject of our visit. The conversation heats up immediately. The term ‘infidel djinn’ crops up repeatedly. And more people join us, speaking over each other, eyes sparkling and hands fluttering energetically at us.

They’ve been here six weeks now. There are good pastures around, and the buildings provide seasonal shelter from the rain, wind and storms. But when the sun hides, the lights and sounds often break the night: gun fire, distant helicopters, sometimes the wheezing of drones flying overhead. The animals are frightened, and sometimes change course without warning. ‘It’s like they can sense danger ahead,’ one of the men says. ‘They don’t listen to us and they see things we can’t see.’ Some of the animals are even refusing to give milk.

It’s not the first time they have encountered the djinn. Apparently, everyone in the desert is used to them; but they seem much worse around here. They are now waiting for the rainy season to stop so they can move on.

I ask if any of them has seen one of these djinn from close by. ‘Amr!’ the sheikh exclaims. Amr! Amr! they all agree. Amr is promptly dragged out from somewhere among the tents. He is a youth of no more than eighteen. He has a smooth, frightened face. He looks at me for a moment, uncomprehendingly, and the men nudge him to speak.

It happened shortly after the sunrise prayers. He was milking his father’s goats when the animals suddenly started bawling and getting restless. As he got up and turned to look behind him, he almost stepped into the apparition. Amr must have been very young when the Americans first came to invade his country, but almost everyone in these parts can recognise the iconic image of the American soldiers. It was one of them, he is certain of it. The soldier was tall, and his face was white and glistening with sweat. He had a thick beard, and his uniform was tattered and filthy. The soldier clung to his rifle in a rest position, pointing down to his left, hugging the butt against him like it was his last tin of food.

He was looking at him – he emphasises this word, because the eyes of the soldier were hard to see. They were like holes through which Amr could see the red dusk light of the desert summer. He could see through the apparition’s flesh, which seemed to be made of dust, like the shapes you spot in a cloud. Terrified, the boy sunk to his knees. Amr was sure he was going to die – it even occurred to him that he was already dead. Then, as he pressed on the ground with his eyes tightly shut, he felt something cold brush past him, through him like a shiver. He prayed intensely for some time, and when he looked up the soldier was gone and his father was standing there, ready to reprimand him. Amr spent the following three days hiding in his tent.

Over lunch (a delicious lamb kapsa) people offer their testimony. Zulema, one of the elders, says that the infidels have been denied the afterworld and condemned to suffer in their own souls the pain they inflicted on the Arab people. Some of these men have fought in the resistance and must be proud of their victory over the once supreme American empire. During those last, endless weeks, as the US troops beat a hasty and chaotic retreat, the insurgents took the fight to the streets of the villages. Low on food, ammunition and morale, bands of US soldiers turned to roaming the desert and the roads, laying siege to villages and scavenging supplies, while the US government and media blamed the atrocities on sectarian warfare. Many troops succumbed to dehydration and delirium, while others were picked off one by one – some of them by these very hands that gesticulate in front of me.

After lunch, I leave Khaled with the clan and I wander through the camp, trying to stay in the shade. As I scan the distance, I find myself expecting to see one of the American dead. But it is too early and too still, and the desert stands timelessly in the searing air, impervious to any human thing.

I realise a group of children is following me and recognise some of the faces from our welcoming committee.

‘Are you American?’ one of the children asks me in English. The faces gather around me expectantly.

‘No,’ I say as emphatically as possible.

‘You’re looking for the djinn,’ the one who looks the oldest says. The children appear excited rather than frightened by the notion of these ghosts, if indeed that’s what they are. They lead me away into the heart of the ruins, where a pack of emaciated dogs (which look more like wolves) is huddling in the shade. The children shout at them and, surprisingly, the dogs retreat obediently. The children reach a pile of debris and form a circle around it. I see nothing but ruins: broken bricks, shattered concrete, pieces of fibreglass and plastic sheeting, rusty pipes and sand – sand everywhere. Except that there’s half a brick wall standing in the wreck and behind it the children have been amassing their treasure. Under a canvas flap with burnt edges, dozens of helmets have been carefully arranged in a pile. The children point to the names and slogans scrawled on the side: ordinary names like Jones and Andrews; clichéd and obscene mottos about victory, pussy, blood and death. They show me the rest of the collection: a handful of name tags, a pair of broken binoculars, Coca-Cola cans riddled with bullets, pens, boots, watches, water bottles. I notice three of the youngest children are standing guard some distance away, and I gather their parents don’t know about this. They are watching carefully for my reaction, which is a mix of dismay and fascination. I promise them I won’t say anything to the adults. Although most of these children are too young to remember, they would have lost mothers, grandparents, uncles or other relatives during the invasion. To them, the American soldiers must be mythical creatures, dimly remembered, who once held power over life and death. And yet, these monsters of legend can’t harm them anymore. One of them, he must be ten years old, puts one of the helmets on and screws up his face. Attention, he shouts in thick English. Kill! Kill! The others find this hilarious.

Then, a reverential silence falls on the group as, rummaging in the pile of remains, one of the older children unveils the most precious items in the collection: an eroded M4 carbine and a dusty SAM-R rifle with a crooked barrel. I notice with relief that the magazines are missing; perhaps there are bullets in the chamber, yet I doubt they would work. The boy lifts the carbine carefully and shows it to me; he is evidently the only one authorised to touch it. The children are not laughing now. They stare at the weapons with the awe reserved for religious objects.

The shadows lengthen around us. As we walk back to the encampment, the children recover their former merriment, laughing and trying to trip each other. I strike a conversation with the oldest one, the one who has shown me the weapons. As the hangars come into view, he asks me if the Americans will come back. I try to assure him the soldiers are gone forever, and that those tales about their ghosts roaming the desert are just that: tales. ‘Insha’Allah, they can’t harm anybody.’ He seems happy to hear this, and hops back to join the other children.

Day 10.

Khaled is gone now and things are rather lonely. I’ve been working on the material we’ve gathered, which doesn’t add much to what we already had. Amr’s story is definitely the closest we have come to encountering the American djinn. I believed him, I believed those eyes, yet that alone won’t make it more believable to my prospective audience. I’ve spent most of the last two days bouncing around the net: hauntings, UFOs, the unexplained, whatever. I’m getting nowhere and, worse, I know it.

When the light goes down and the temperature becomes more bearable, I wander through the souks of Aljazhab in the vain hope of finding inspiration. The souks are a labyrinth of cobblestone streets sheltered by high and magnificent stone archways. Many of the streets are like tunnels where you constantly have to dodge hawkers, donkeys, barrow-pushers, vans and African peddlers. There are vegetables, delicacies, quartered animals, fabrics, spices, trinkets and every conceivable type of narjileh. I get lost in the hypnotic, fractal complexity of the patterns on glassware, textiles, copper and silverwork. I sit down at the cafes and play chess with the locals. I get beaten every time.

In one of the alleys leading away from the markets I come across a statue of a Hittite king, portrayed riding a lion and staring into a far-off horizon that must be still there, somewhere. I stare into his large, almond-shaped eyes, at his square, frizzled beard. If he was alive now, I don’t think the modern world would seem that strange to him. On the grimy backstreets of the souks, the walls and wooden beams are plastered with the faces of the martyrs: children, women, men. They all have names, scores of nameless names. I’ve even come across posters of Osama bin Laden flapping in the breeze. I wonder who remembers and if it matters. I wonder whether forgetfulness and historical amnesia are not, in the end, the best solution. I guess that, if the story sinks, I can come up with some alternative. Perhaps I can do a piece on neo-pan-Arabic nationalism, or on post-war Qiram, or the al-Qaeda Party. Maybe I could interview al-Zhara himself.

My next stop is Jezzir-el-Awr, the last town before the Syrian border. I get the impression that everyone here accepts the reality of the infidel djinn without the slightest surprise or perturbation. It makes perfect sense to them: they already have a place for these things in their cosmology. I’m beginning to grow envious of their certainty, their belief in a universe that is just and meaningful.

Day 11.

Jezzir-el-Awr lies on the eastern bank of Nahr Al-Furat, an old farming settlement that suddenly struck it rich when light crude oil was found in the area in the mid-1980s. Lots of Bedouins and peasants of the Gezira pass through the town. During the US invasion, the troops promptly took over the installations and claimed the production. They built a refinery so the stuff came out ready to feed the planes, drones and vehicles. It was the first place that the insurgents reclaimed in the early days of the collapse, and it was a miracle that the whole thing didn’t blow up. The Americans built a military base and a whole new suburb, each as large as the old town itself, to house contractors, officials and workers. At one point there were three security personnel per civilian operator, plus a whole infantry division on guard. The suburb was a surreal vision of small-town, middle-class USA in the middle of the desert, still visible below the layers of Middle Eastern kitsch: arabesque wrought-iron fences, faux Persian gardens and added-on turrets. The massive Hummers waiting on the driveways, I guess, have stayed the same – minus the oil, of course. After the defeat, the shopping centre was torn down and replaced by an impressive mosque. They kept the car park, a sea of asphalt five degrees hotter than the surrounds. Welcome to al-Zhara’s cultural revolution.

My hotel room overlooks a jumble of dusty rooftops. I can see the souk in the mid-distance and, beyond, the levy banks containing the river. Tropical vegetation covers the banks, extending into the empty spaces of the town and beyond. I wonder how long it will be before some primeval Mesopotamian creature crawls out of the jungle.

I’m sitting now at a cafe by the pedestrian suspension bridge, sipping shay and waiting to immerse myself in the long sunset, as soon as I finish typing. For once, I can fool myself I’m on holidays. Tomorrow, the oil rig. I’m giving these ghosts one last chance.

Day 12.

Well, that was the last chance. I’m flying back to Berlin in two days.

In the old days, by this stage, I would have had a wastebasket full of unfinished drafts and false starts, furiously crumpled and stuffed into the bin like I was trying to drown some enemy in a bucket of water. Now, instead, I have a virtual folder sitting somewhere on a remote server, containing all the shameful back-ups that one day I’ll have the courage to delete. Call me old, old-fashioned, whatever, but I miss the days when things were things. The feeling is the same, though: that depressing emptiness of a story going nowhere. Luckily I found a nice underground bar, catering mainly to foreigners, where the alcohol laws are relaxed or overlooked altogether. I’ve been drinking a lot, every night, striking conversations with the young travellers. In the mornings I watch interminable Egyptian soap operas in the hotel’s common room, drink Turkish coffee and watch the procession of Israelis, Czechs, Canadians, North Africans, Indians, Chinese and Americans from both South and North. They are a new breed of tourist, disillusioned and impoverished. Many of them strike me as withdrawn and aimless. Yet, overall, most of them seem at peace. The peace that comes from having no expectations, I guess.

Yesterday afternoon I finally drove to the rig. It looks like the abandoned playground of a giant child, scattered with upturned water tanks, sunken shacks, collapsed fences and drill pipes. Everything is covered with a thick layer of sandy dust. Dark-green creeping vines have pushed through every available interstice. The derricks lean precariously, and the cable spools and hoisting systems dangle from exhausted beams. The mud-pumps and control houses are almost completely submerged in weeds and soil. There are four hammer pumps frozen at the peak of their upward thrust, a slightly menacing gesture that has been left forever unfinished. A fifth hammer has collapsed, crushing onto a row of diesel engines.

Nothing remains of the adjacent military base; weeds and thickets of long reeds rim the squares and rectangles of dirt where the buildings have been. It has rained for three days now without a break. I stayed in the car, watching the motionless structures, waiting for something to happen, for someone or something to appear. The long twilights here remind me of the eerie Australian skies during the Summer of Death, the bushfire season that brought the country to its knees. It’s hard to believe that it’s been nearly two decades since that happened. That was my last summer in my homeland. Smoke and ash blanketed the sky, and shaped the light into otherworldly streaks of pink and white. I haven’t thought of this in a while. The desert is doing things to me. It’s now two in the morning and the dark feeling of homesickness remains as intense as ever. In any case, the rain gave me a welcome excuse to stay in the car. I wasn’t afraid of ghosts, but of something worse, I’m not sure what it was. The best way I can describe it is that I was afraid of a void, of the possibility that there was nothing out there at all.

Day 14.

I’m writing this quickly, demons biting at my heels – not metaphorically. I started writing what follows at Dubai airport. I puked out an early draft during the five-hour wait for my delayed flight (ash cover, solar storms, the usual), sunk into the plush couch at the Lufthansa VIP lounge, unable to move and trying to make sense of what had happened. I felt disconnected. I watched myself from above. I’m just now starting to come back down into my body and my senses. The things in my apartment are coming into focus, their strangeness turning into some sort of spurious familiarity, as though someone had replaced them with identical copies during my absence. My stomach is paying the price of all those vodkas, peanuts and canapés. But I need to put down the facts before they slip through the crevices at the bottom of my mind. Before I start questioning the whole thing as some sort of hallucination.

Jezzir-el-Awr, 1 am. I’m drinking at the traveller’s bar like every evening. It’s a quiet Wednesday night and there are around twenty people in the bar, most of them backpackers. The dull background sound of the rain pattering outside is still audible below the music. The place is set up like a Turkish cafe, with cushions and burning lamps on the tables spreading a dim and cosy light. It’s pure kitschy fantasy, of course, but comforting. I’m sitting in one of the booths at the back of the place, propped on some cushions, my palm book abandoned on the table.

I am beginning to doze off when I hear the voice.

‘I’ll stay for as long as I like, buddy!’ The sound is booming yet somehow distant, as though coming from the other side of a wall. I’m startled by the accent: a thick southern US drawl I haven’t heard in many years. It hits me before I can even decipher the words.

At the service area, a bulky shape is tottering drunkenly away from the bar. As far as I can make out, the man is carrying a large backpack and equipment of some kind. The two men serving behind the bar stare hostilely at the newcomer. A palpable sense of fear has taken hold of the place. Two young tanned girls, probably from Northern Europe, are retreating cautiously.

I have trouble focusing on him. In the dim light, I piece together successive glimpses into a more or less stable picture: short cropped hair, pasty white skin, a tight tank top, round Lennon-style dark glasses. He’s tall and muscly in a gym-junkie kind of way, but he looks haggard and underfed. His flesh is colourless, as though his body has started feeding off its own muscle. I can’t make out what he is carrying, but I know. I suddenly know.

I try to disappear into the cushions and make myself inconspicuous. But then the man turns around and scans the back wall where the booths are. I notice something different, a subliminal change. It takes me a full minute to realise the rain has stopped. The doors of the bar are open, flapping to the beat of a sand storm that has wakened, suddenly and inexplicably. The Arab electronica playing softly in the speakers is not enough to dispel the silence.

Yes, I’m afraid, almost in shock. My blood has stopped in its tracks. I realise too late that I’ve been staring at him fixedly for some time. He has spotted me and I’m the only one left in the booths. I look away, but I can feel his eyes on me.

I press my fingers around the glass, trying to evoke some response from my numb limbs. As he approaches, I make out camouflage pants and a torn backpack. An assault rifle with telescopic sight dangles at his side, pointing to the floor; he drags it as though he has forgotten about it. The silver tags twinkle in the light. I see the scars, the peeling skin on his face, his tall army boots caked in sand.

‘Hey buddy, you don’t mind if I sit here, do ya?’

It’s not a question. The guy falls on the seat opposite mine. His body makes no sound. His dirty glasses mirror the orange light from the lamps, and his eyes are visible in glimpses, dark and shifting, of an indeterminate colour. I avoid looking into them.

It is hot in here. He should smell of stale sweat and bad breath, but I can only pick up a vague scent. Like meat gone off in a distant kitchen.

‘Can I have a taste of your drink, what is it?’ he asks. ‘Looks like a lady’s drink.’ He casts a glance behind him. ‘They won’t serve me over there.’ His voice seems to come from another direction, somewhere behind him and to his left. I stare at my glass. ‘Come on buddy, they’re refusing me a drink, they always do around here. Ungrateful vermin.’ He slaps down something on the table. ‘Come on, my round.’ I have not seen Washington’s face for so long, the memories are almost overwhelming. ‘You just gotta go to the bar, play barmaid.’ He reaches for my half-empty glass of vodka and cranberry. I retreat instinctively. But, as his blunt fingers are about to touch the glass, he withdraws them with a pained expression. ‘Are you always this quiet?’

‘You took me by surprise. I … I didn’t know you were operating in the area.’ My voice sounds thin and constrained.

He cocks his head to the left and smiles, showing a row of straight, white teeth. ‘That’s better. Much better. Lemme introduce myself. The name’s George Francis Johnson. Corporal Johnson, 3rd Division of Infantry, Marine Corps, United States Army.’

I hear myself say my own name in a wheezing whisper. I can’t believe what I’m doing. I doubt he’s caught my name, but he nods. ‘Sure,’ he says. As he moves his head, I can see glimpses of dull light coming from underneath the glasses. The glasses are not tinted. They only seem dark because of what is happening beneath them.

My inner journalist is taking over. He can’t hurt me, I tell myself. He can’t hurt me. ‘You must miss home, Corporal. Whereabouts in the States are you from?’

‘From Georgia,’ he responds immediately. He pauses, gauging my reaction. ‘Long way away, yes.’

‘Oh, I’ve been to Georgia. Nice part of the world.’

He seems to relax and sinks into his chair. Without prompting, he starts telling me about his childhood and his family. He has two sisters, both are nurses now, his father was in real estate. The Global Financial Crisis screwed him.

As his words drift in the air, I realise he’s talking to himself, clinging to the fading memories. With each word he seemingly becomes more real. And when silence comes, he drifts away once more. Could it be that he doesn’t know what’s happening? Time is ticking by and my inner journalist is debating himself. This is the opportunity of a lifetime, yes, but who is going to believe me?

‘Corporal,’ I say, ‘why are you here? I mean, fighting this war?’ A risky question, likely to bring up conflicting emotions. I can sense his rage, but I get the impression he has asked himself the same thing countless times. I glance into his eyes, but the lenses of his glasses are now a smooth obsidian.

His answer comes out mechanically, like a rehearsed speech. ‘We’re fighting this war against the enemies of freedom, those who hate the United States and want to kill us and rob us of our freedom.’

‘And why do they hate you, Corporal? Why do you think people hate the United States?’

I regret the question the moment it leaves my lips. I sound sceptical of his motives. But he takes it well, and thinks about it. ‘Because they … They have to hate somebody, and America is the most powerful, richest country in the world. And they look around for someone to blame and say, “Well, let’s get them.” I guess.’

I nod politely, like a therapist. I want to be out of here. There is a sudden pain in my chest, I know it too well. But I have to keep talking, keep him focused. ‘It’s been a long, bad war out here, Corporal. When are you going home? Do you know? You must miss your family.’

‘Soon,’ he says. A breath of air caresses my face: the smell of hot sand, desert, petrol. When he sticks his hand into his pockets, I give a little jump. He pulls out a piece of paper and places it gently on the table, halfway between us. I lean across the table. It’s a photograph. A blurry photograph of a young girl, smiling: two blonde pony tails, a red dress that seems too large for her. She must be five years old. ‘Sally’s her name. Haven’t seen her …’ He frowns. ‘In some years, I guess. She’s in third grade now.’

Beyond him, the place is empty. The two barmen are standing in their place, their shadows watching us. ‘Did your wife send you this?’

He hasn’t heard me. ‘The desert’s a hard-arsed bitch. But we will win this war. Like we’ve won all the other wars.’ He shuffles in his chair and looks around, disoriented. He seems to have lost all interest in me. ‘It might take longer than anticipated,’ he says to the door.

I nod in silence and stare at my empty glass. My eyes are filling with tears. It’s the sand, I tell myself. It’s the sand. ‘Good luck, soldier.’

When I open my eyes, he’s gone. Outside, it has begun to rain again. On the table, there’s a thin rectangle of dust where the photograph has been. On the seat, a few handfuls of sand trickle onto the floor like the filling from a broken hourglass.