Affirmative: Zoë Rodriguez

As a lawyer who’s worked for a number of years at the Copyright Agency, I am genuinely in favour of copyright and believe that writers and others who create works are served well by it. I’ve spent quite a bit of time explaining to authors that copyright is a tool that enables them to manage their creative capital, and that they should value it and understand how to use it in effective ways for their circumstances.

As this is a debate, a definition is required. Copyright is a personal property right usually granted to authors under the federal Copyright Act 1968. More exactly, copyright is a bundle of rights that covers the different things you can do with works. In relation to text this includes the right to publish, photocopy, digitally copy, adapt, and a more recent right that takes into account the internet and posting works on websites or emailing them: the right to communicate. Rights granted are for original works that have been reduced to a material form (for instance, written on paper or a computer). Copyright does not protect mere ideas – it protects the original expression of ideas.

Next definition: writer. With almost universal literacy in Australia, perhaps everybody might be called a writer. For this debate, I limit my definition to someone who creates original text works with a view to them being read by others.

But why do writers need copyright?

The argument is that copyright rewards creators for their effort and encourages the creation of new works for the community to enjoy. Copyright is a challenge for creators to live up to their name and be creative. Simply cutting and pasting isn’t enough for rights to be granted in works, and may even land the person recycling other’s work in hot water, since the owner of the original can pursue for infringement.

Some argue that copyright is stifling creativity – that ‘creators’ should be able to access other people’s work without impediment. But copyright in itself does not impede access to works – books can be viewed (accessed) in libraries or after purchase from bookstores or on loan from friends. No author I’ve ever met wrote with the ambition that their works not be accessed. They wrote because they wanted to be read.

Many great writers frequently cite their wide reading of works by other authors. Copyright has not prevented them from accessing these authors or their books; and while these books might sometimes influence the development of a new work, the writers don’t merely copy existing texts – they write works that are distinct and original.

On this basis, I do not agree that copyright is a barrier to the creation of new works. On the contrary, I think it is a key ingredient in ensuring that original stories are told. It provides an economic return for the time, talent and experience that authors put into creating works.

Those who suggest that removing copyright would lead to a ‘democratisation of ideas’ and a consequent flourishing of creativity are ignoring these issues. They are also advocating a society oddly biased against the interests of those who earn their livings from their creativity. It is a form of selective nationalism: we don’t ask a baker to give away loaves of freshly baked bread for no payment, a teacher to teach future generations for free or an accountant to calculate our taxes without the prospect of earning a fee for their work. Yet some say that copyright, which provides a system for authors to trade their works, should not be enjoyed by the writers whose works enrich our intellectual lives and tell our country’s stories.

Additionally, their view ignores the comprehensive repertoire of exceptions to authors’ exclusive copyright where it is considered to be in the public interest – that is, for private research and study, for reporting news and so on.

I don’t subscribe to the view that writers should have to find other ways of monetising their work – through joining public speaking circuits, merchandising etc. Many writers don’t or can’t do this sort of work: their major ability is to craft written works. If the community wants to read them, it should pay its creators appropriately. As with other personal and real property rights created under law, it is an author’s choice to offer their works for no payment, and our copyright law allows this.

What of Digital Rights Management (DRM), used to identify works, control access and protect licensing terms? Why on earth does an author need this?

DRM was recognised in international and Australian law because of the acknowledgement that in the online environment, where perfect copies of digital originals can be transmitted in limitless numbers to limitless places, digital tools were needed to provide protection, in tandem with the copyright in the underlying works to which they are attached. But what’s the point when spotty-faced teenagers crack the locks in nanoseconds, and when the technology often frustrates those who would like to be law-abiding citizens and purchase books from their favourite authors?

I’d argue that burdensome access controls may not be the answer, but DRM systems that assist in efficient, consumer-friendly trade in digital works are almost definitely a part of the solution. They will mean that reading audiences are able to find works they want to read easily.

The publishing industry is in a period of dramatic transition. Traditional business models are being challenged and unsettled by the digital revolution, and authors (and publishers) are having to innovate in response.

But the requirement for quality content will never go away. Central to human activity is the telling of stories. Progress depends on recording history for future generations. In an era where we rely on monetisation to exist, our authors must have a framework which enables them to have their intellectual output valued and copyright (with its associated DRM tools) – and in association with renovated business models – will be the answer.

Rather than arguing the requirement for writers to have copyright and DRM, I’d prefer we all put our intellectual mettle to the challenge of devising workable business models – fair to our writers, and fair to the community at large.

Negative: Ben Eltham

On any historical analysis, the question of whether writers need copyright is frankly nonsensical. Literature is an art form that predates the invention of writing itself. Copyright is a special form of intellectual property invented barely three centuries ago. Ever since, it has been more honoured in the breach than the observance.

Copyright may be many things – a foundation of industrial business models, a key revenue stream for authors and a social construction of technology – but one thing it is not is a universal right. Indeed, copyright can claim no heritage in English common law, perhaps understandably, given the fundamentally oral origins of that corpus.

Copyright, in fact, has always been an essentially utilitarian regulation, and the arguments in its favour are almost always consequentialist in their construction. That is to say, the arguments for copyright are generally about the rewards it offers for its owners, and the incentives these rewards might represent for would-be creators. I will argue here that, while these rewards are real, they are scarcely necessary – either for writers themselves or for the creation of literature.

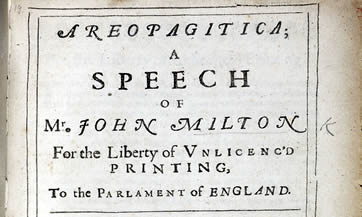

The backstory of the Statute of Anne, the first formal copyright legislation in the United Kingdom, is as good a place to start as any (the following discussion draws heavily on the work of copyright scholar Ronan Deazley). In seventeenth-century Britain, the print medium had been tightly regulated by the Crown, namely through the Stationers’ Company, made so notorious by Milton in Areopagitica. The Stationers’ Company had a monopoly on printing but was also responsible for censorship. In order to enforce this, it had wide powers of search and seizure, as well as the right to copy works of literature in perpetuity.

As latter-day representatives of content industries would discover, the punishment of pirates is not necessarily popular, and the Stationers’ Company made many enemies in the vigorous pursuit of its vested interests. The late seventeenth century in England was a time – again, rather like our own – in which libertarian ideas of intellectual freedom enjoyed a growing popularity. In the wake of the Revolution of 1688, a new Whiggish atmosphere swept London. No lesser a figure than John Locke was influential in the public debate over the laws of publishing (indeed, the idea of a public debate was itself new). The Licensing Act, which had governed the Stationers’ Company and the printing industry since 1662, eventually failed to find parliamentary support and in 1693 was not renewed.

While the victory against censorship was justly applauded, the economic consequences of the end of the Licensing Act should not surprise us. With the collapse of the monopoly, England suddenly opened its market to foreign booksellers. Prices of books fell; previously protected publishers and printers went out of business. And Big Content mobilised, exerting plenty of lobbying effort to get its industry protection reintroduced. No fewer than twelve separate attempts were made to pass a new law granting publishing monopolies.

As they have ever since, publishers enlisted the voices of authors in their campaign. That noted polemicist Daniel Defoe was particularly prominent (‘One Man Studies Seven Year, to bring a finish’d Peice into the World, and a Pyrate Printer, Reprints his Copy immediately, and Sells it for a quarter of the Price’), along with another pretty handy writer called Jonathan Swift.

The upshot was the 1710 Statute of Anne, a new law to regulate publishing copyrights that granted monopoly rights of publication and reprinting to authors. It reads, in part:

Whereas Printers, Booksellers, and other Persons, have of late frequently taken the Liberty of Printing, Reprinting, and Publishing, or causing to be Printed, Reprinted, and Published Books, and other Writings, without the Consent of the Authors or Proprietors of such Books and Writings, to their very great Detriment, and too often to the Ruin of them and their Families: For Preventing therefore such Practices for the future, and for the Encouragement of Learned Men to Compose and Write useful Books; May it please Your Majesty, that it may be Enacted …

The statute thus makes clear the twin goals – undeniably utilitarian and consequentialist – that have framed copyright jurisprudence ever since. First, copyright is an industry protection: a restraint of free trade in the form of copying and reprinting. Second, it is an incentive for authors to create.

How do these arguments stack up in the long run? Where enforcement has been successful, copyright has been very successful as an industry business model. Barriers to entry, being in general a handy competitive advantage, offer a legal framework that has in many cases given rise to industrial cartels and has been of inestimable value to the owners and shareholders of publishing enterprises down through the ages. The analogue and physical nature of the book has been such that rampant digital piracy has only very recently been a problem that the global publishing industry has had to grapple with; it’s fair to say that during long periods of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries publishing has, at very least, not had to contend with any serious technological challenges to its business model. Of course, there’s no accounting for taste, and so publishing books for a living has always been a fraught and risky business. But the modern multinational publishing industry would be inconceivable today without the strong twentieth-century armature of copyright regulation that constructed the high tariff walls and national territory silos that are only now beginning to break down.

For writers of books and other literary endeavours, the evidence is also in. Copyright matters little as an incentive, because economic incentive means little to most authors. There is little sociological or literary historical evidence to support the claim that copyright is necessary as an incentive to secure the creative investment of authors. In fact, millennia of human experience before the invention of copyrights suggests the opposite. Even today, most authors quickly sign away their copyrights to publishers at the first available opportunity in return for cash advances, which suggests the real value of copyrights for authors is as a bargaining chip to sell to publishers for income rather than as an inalienable precondition of literary creativity.

Should we really doubt the absurdity of the idea that a legal structure of intellectual property is necessary for the practice of literature, we need only turn to the vast literature of protest and prison writing that adorns the history of totalitarian societies during the twentieth century. Do we really think Solzhenitsyn or Soyinka were calculating their royalties while they furtively scribbled away in captivity?

Thinking it through, the relationship of copyright to literature is largely industrial, not existential. Property rights may be beloved of economists, but they are no more a prerequisite for literature than a modern banking system is required for humans to trade.

Response: Zoë Rodriguez

So it seems that Ben Eltham would have it that artists should go back to their garrets and starve, writing out of an overriding desire to create, with no sullying of this pure pursuit with the disgustingly materialistic desire for money.

According to Eltham, most authors are not interested in economic reward for their writing. I don’t know the writers he’s thinking of, but they’re certainly not the ones I come across daily in my workplace – those on the phone asking about their payments. At Copyright Agency we have over 16,000 individual creator members and distributed over $140 million in 2011/12 from licence fees we collected. These are significant and sustaining contributions to Australia’s creative industries.

To bolster his argument, Eltham’s thrown in the examples of authors who’ve written from imprisonment. Certainly in these dire circumstances we can feel fairly confident that the first concern of authors is not about the pay they will get for their work but about the freedom to create it. That’s why authors formed the international organisation PEN which campaigns tirelessly for the release of imprisoned authors across the globe and for their right to freedom of expression.

This group does not see copyright as foreign to their interests but complementary, even issuing a declaration at their annual congress in South Korea in September concerning copyright and associated digital rights.

The notion that authors will write no matter what may be true for some. There will, however, be many others who are dissuaded from writing because they, like the rest of us, need money to sustain themselves and their families. Prior to copyright laws, authors were dependent for publication and payment from patronage, for the church or state or wealthy citizens to commission works – clearly a form of censorship. While great works no doubt came out of this (I’m travelling through Italy at the moment and the Uffizi Gallery in Florence is a demonstration of the Medicis’ power), is this really the way we want to operate?

Can we realistically have such a situation in a mixed-market economy, anyway?

The beauty of our copyright system is its great flexibility, and the rights that it bestows on all who create something truly original. No doubt copyright will be pushed and pulled to adapt to the evolving digital environment, but there’s nothing about that stopping anyone from creating new works. In fact, it’s more possible than ever to create and distribute content. Traditional barriers to trade in the form of costs of publication are greatly diminished: anyone with access to a computer and the internet can offer their works to the globe. Yet, most readers will still seek quality content from skilled writers – and more often than not, from works that have been polished by caring, experienced editors and the other staff in publishing houses who help bring content to the public.

Why, I ask, is money a dirty word for the creators in our arts landscape? Festival and centre directors expect to get paid and so do copyright lawyers – and yet the people who make our careers possible somehow shouldn’t? And it’s important to remember that the industry standard is for authors to enter into publishing arrangements where they share in the economic life of the work through royalty payments based on sales, and often these contracts contain reversion clauses so that rights return to authors when the work is no longer being commercialised by the publisher.

Copyright (and associated digital rights management) is the mechanism we have created to enable writers to get paid.

Response: Ben Eltham

Zoe Rodriguez contends that copyright ‘rewards creators for their effort and encourages the creation of new works for the community to enjoy’.

The problem with this assertion is that there is so little evidence for it. Perhaps that’s why Rodriguez doesn’t bother to present any. Of course, I agree with her that copyright does exist and that some writers make a fine living off their royalty streams. But this is the exception, not the norm. Most literary works produce negligible copyright income, and most writers barely make a living from their work, as an increasingly extensive sociological literature about the working lives and incomes of artists shows.

The most recent and best data on writers’ incomes in Australia is by economist David Throsby, and was gathered with the assistance of the state writers’ centres and the Australia Council. Writers emerged with the lowest mean and median incomes of all the artists Throsby studied. Their mean creative income was about $11,100 in 2008 dollars, equivalent to approximately $12,100 today. That’s bad enough but, as Throsby notes, the median income was even lower, at approximately $3600. That means half the writers he surveyed earned less than $3600. For emerging writers, the figures were even worse. ‘Around two-thirds of writers who are members of writers’ centres earned less than $1000 from their creative work in 2007/08,’ he concluded. And royalty revenues were only a proportion of the cited figures, which also included fees for service and government grants.

The poverty of a literary career is hardly a new discovery, nor one confined to contemporary Australia. So if the chance of future copyright incomes really is a key motivation for writers to start up their word processors, it’s a peculiarly unrewarding one. Are writers really writing for the money? If they are, they’re pretty dumb.

The more you examine the copyright-as-rational-incentive argument, the less convincing it becomes. Some of the better-paid writers in our society, such as newspaper columnists, advertising copywriters and corporate speechwriters, sell their services with no expectation of future royalty revenues. For these creative professionals, the nature of their labour market means that any royalty earnings are likely to be owned by their clients.

The typical struggling novelist faces a different sort of problem that also undermines the idea that copyright is a necessary reward for literary endeavour. It is unpopularity. By definition, little copyright income accrues to writers whose work is unknown – the vast majority, of course. The motivational benefits of copyright continue to be justified by the undeniable wealth it bestows on a few, rather than by the desultory pocket money it dribbles to most.

Perhaps the clinching argument for the irrelevance of copyright to the pursuit of cultural endeavours can be seen in the music industry where the last decade has given us a wonderful natural experiment in the role of copyright as a motivator for creativity. Since the beginning of widespread music piracy in the late 1990s, sales of recorded music have collapsed. So have the royalty streams attached to them. No corresponding decline in hopeful young musicians has been observed.

The most depressing aspect of Rodriguez’ paint-by-numbers effort is the unconscious neoliberalism that constantly seeps through her vapid analysis. ‘In an era where we rely on monetisation to exist,’ she writes, ‘our authors must have a framework which enables them to have their intellectual output valued.’ It’s a conflation of the profit motive with the value of literature that is as complete as it is disheartening. If it were true, then non-monetised forms of writing would not exist. Thankfully for literature, especially poetry, writers are still writing, regardless of the potential monetary benefits.

I have no quibble with writers making money from their work, nor with the concept of an intellectual property right for literature. But to argue that the latter is required for the former is simply false. This lazy confusion of the institutional self-interest of the copyright industry with the pursuit of literary art is worse than intellectually dispiriting. It is morally corrosive and profoundly self-deluded, to boot.