‘The progress is always of money into someone’s pockets. And this time the advance may be through my rose garden.’

Kylie Tennant, Foveaux (1939)

In the near constant debate about housing affordability, it can be hard to distinguish empty policy chatter from genuine proposals based in well-grounded analysis. This is, in part, because property developers and businesses, along with parts of the media, run a concerted campaign to urge governments to fix the housing crisis with ‘supply-side’ solutions.

According to historian Brent Cebul, supply-side economics has served an accord between the state and capital since the post-war period, displaying what Justin Vassallo calls the

propensity to preserve—and effectively underwrite—the discretion of private business over major investments that shaped the general welfare of local populations. [I]ts goal is not to reserve spheres of the economy for long-term public ownership, but to use state stimulus, various public-private bodies, and regulation to make private investment more productive.

In other words, supply-side policy removes the barriers that make capital allocation into housing attractive. This results in loosening regulations for property development, isolating zoning decisions from democratic control, and opening new, protected avenues for capital accumulation in the heavily financialised world of making profit from social needs.

A recent offensive in this campaign was conducted by the Australian Financial Review. The magazine’s ‘Housing Supply Crisis’ series featured startlingly self-referential ‘think-pieces’ on, for instance, why some of the richest suburbs in Sydney (like Mossman or Hunters Hill) should embrace medium-density housing development. Never mind that the median house price in Hunters Hill is around $4 million, and residents earn twice the national average salary. Bulldozing (or re-allocating all the homes in) the richest suburbs may indeed ‘bring the crisis home’ to those who profit from it, but that’s not the message. As the campaign’s title announces, the conclusion comes before the analysis for businesses. The question is how to make the numbers line up in obedience to the point you want to make.

Tony Richards, for example, highlights the constant supply of ‘reports in recent years highlighting the importance of greater flexibility on the supply side of the housing market.’ Without offering evidence for the claim, Richards dismisses a range of other possible causes for unaffordable housing with the comment that ‘it seems likely’ that supply is the main cause. His main target are NIMBY local councils and governments that—– without supplying a single example—he accuses of corruption.

In another contribution to the series, John Kehoe quotes the Centre for Independent Studies’ Peter Tulip: ‘if you restrict the supply, the price will go up and lead to illegal activity and you typically get bribery.’ It’s a logical sequence that only the entirely abstracted world of free market economists could dream up (whilst ignoring its application in any other industry where supply is regulated, such as pharmaceuticals).

The Review journalists live in a world of cherry-picked statistics in which, as Kehoe writes, ‘rents have broadly tracked incomes over the past 30 years’—a fact that even the Reserve Bank of Australia knows to be far from correct. With factors like financial deregulation, increasing wealth concentration and garrisoning rental stock in short-term, high-price leases dismissed, Richards finds it ‘hard to escape a conclusion that the run-up in the price of housing over the past two decades must be related to inflexibilities in housing supply.’ This means they can unproblematically campaign for reducing ‘red tape by overzealous local governments’, and ‘remove frictions that are reducing supply’ by making ‘planning and zoning arrangements’ more acceptable to developers.

If you thought this was isolated to the Australian financial press, the Financial Times stepped in to remind us that this is a global crisis with what almost seems like a globally coordinated solution prepared by the amanuenses of capital. Pre-emptively asserting ‘supply’ as the problem, the FT half-acknowledges the crisis-prone tendency of for-profit systems, in which, after the Global Financial Crisis, ‘building a new house wasn’t as lucrative as it was before’—while blaming a rise in labour costs. A second instalment finds an ‘unusual solution to skyrocketing rents’ worthy of RBA Governor Philip Lowe: cosily called ‘homesharing’, it might also be known as a homeowner employing a live-in servant.

Lowe’s own way of solving the crisis is to encourage renters to ‘economise’ and put the ‘price mechanism to work’ by enforcing the economic discipline of poverty, unemployment and financial insecurity with the technocratically detached mechanism of interest rate increases. In so doing, the Governor occupies the same world of abstraction as the financial press journalists in which class doesn’t directly determine housing outcomes for us all.

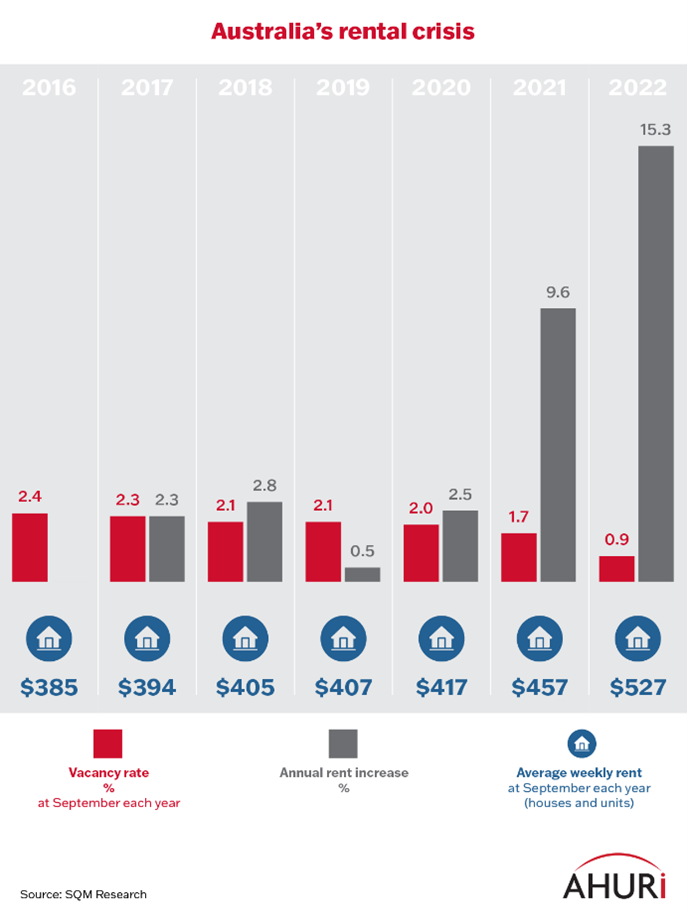

Household formation was altered during the pandemic, exacerbating a long-term trend of single person households up over 17 per cent from 2016–2021. By Lowe’s logic, renters are to be punished for wanting some privacy, a home to make their own. But landlords have already exploited the approximately 1.5 per cent decrease in vacancy rates to hike rents anywhere between 15 and 25 per cent. Lowe admits that rent increases are ‘really hurting some people’ but he must conclude these people don’t matter at the economy-wide scale, or doesn’t really mind that his ‘solution’ will hurt them more (without affecting those responsible for the rent increases).

Two recent government initiatives join the barrage of financial media in recommending reductions to regulation—or to ‘unlock’ supply, as a Queensland Government committee insists.

The announcement of the Committee included another foregone conclusion, this time from an industry group called the Property Council, that ‘land supply was identified as a key issue.’ Since land can’t be easily produced, at least not without incurring the ire of NIMBY Greens Senators concerned with the flood risk for affordable housing developments, increasing land supply means easing regulation instead—including environmental regulation.

In New South Wales, a similar report effectively defended a version of trickle-down economics it called ‘filtering’, which allows ‘more supply in high-demand locations’ by allowing the luxury of ‘high-quality’ developments to occur so that ‘high-income’ occupants move out and leave the supply to ‘middle- to high-income households’ at a reduced cost. In turn, these households leave dwellings that can be occupied by lower income families, reducing burden for social and affordable housing.

This is not even an attempt at window-dressing inequality.

The illusion of a mechanical flow-on effect on price (either of houses or rents) is shared in the AFR by Richards, who argues that ‘higher purchase prices [flow] through to the cost of renting as well.’ But the NSW Productivity Commission’s own version of this claim contains the footnoted caveat that a small dip in house purchase cost has coincided with a dramatic increase in rents.

It turns out landlords are unperturbed by house price decline but, conveniently, very energised by house price or interest rate increases.

Institutional conditions dramatically favour landlords in the housing market, granting them power to set the price for a basic human necessity. Peter Mares has criticised the ‘filtering theory’ in practice since Australia’s tax system encourages financial investment in property as an asset, and has theoretically posited that if filtering were to actually occur, it would amount to a market collapse on the scale of the GFC.

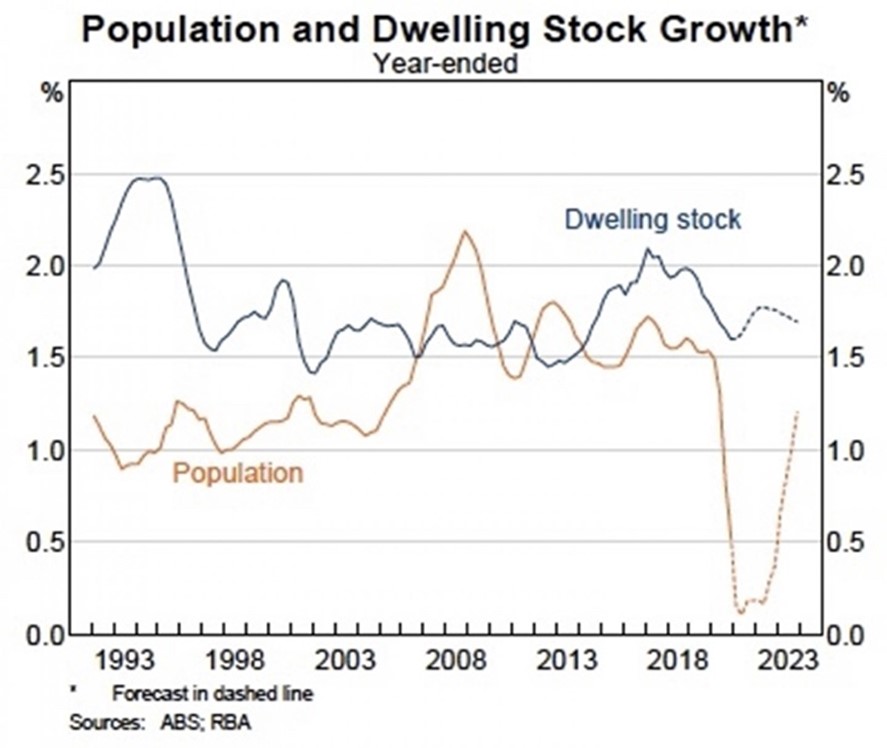

The thesis that supply is ‘locked’ by government regulation is convincingly challenged by Nicole Gurran and Peter Phibbs in both their academic and policy writings. They note that supply-side pro-development reforms—including de-politicising planning decisions over the last two decades—have reduced barriers to residential land release. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute modelling vindicates this finding that ‘planning measures may not be a key factor influencing housing supply.’ Moreover, Gurran and Phibbs question supply-side’s mechanical economic reasoning, especially in the context of pandemic-era affordability, when the drop in migration did not induce a fall in house prices. Affordability in the crisis-prone housing system, which should be viewed in its totality, is vulnerable in part because of financialisation (which can encompass practices such as developers banking land while they wait for the market to turn). But the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute notes that ‘at any point in time [demand] is met from established housing stock.’

Another aspect of the supply-side campaign is its dog-whistle to the anti-immigration right that the nation’s precious housing resources are being used up.

Supply-side housing policy canalises the crisis into a single axis, rather than examining decades-long, economy wide decisions about financial deregulation and favourable tax conditions for capital concentration. As the AFR’s focus on Mossman and Hunters Hill illustrates, you cannot simply intervene on the supply-side without reinforcing existing dynamics.

The Australia Institute observes that ‘there are not two separate markets for rental properties and owner-occupied properties.’ The new supply (even if it’s intended for affordable rental housing) is just as likely to be bought by rich landlords. This is dismissed as trivial by Tony Richards, who claims that

reducing tax breaks for capital gains and negative gearing could change the distribution of ownership between investors and renters, but would be unlikely to improve the overall housing supply.

The inequitable distribution of housing is further concealed by the way interest rate rises are reported—often with the impression that all mortgage holders suffer. It’s not an accident that people with money seem to win regardless of whether interest rates, for instance, are up or down. When interest rates are down, they borrow cheap money to fund capital accumulation and leverage investments, and when interest rates rise they rake in returns and increase prices or rents. Mares reports that

just before the global financial crisis, Australia’s total household debt was estimated at $1.1 trillion, or a little over $50,000 per person. By early 2018, the figure had more than doubled to an estimated $2.466 trillion, or close to $100,000 for every person.

This debt figure must also be placed in the context of declining real wages, as Zacharias Szumer points out. Yet even this startling feature of the intensified financialisation of our everyday lives conceals the vastly different distribution and uses of debt.

This dynamic has been demonstrated by the collapse of construction and development companies in the last few months, including Porter Davis.

According to reports in early April, the collapse was precipitated by pandemic-era economic stimulus HomeBuilder, which approximately doubled land sales in outer suburban estates in 2021. Porter Davis’ vulnerability lay in having fixed price contracts as material costs rose and creditors sought higher returns. The companyؙ—which folded on the same day as civil construction group Lloyd Davis—was tens of millions of dollars in debt, a situation far from unusual for businesses whose limited liability demise passes on the risk of such leveraging to customers (while creditors take priority in cases of insolvency).

In any case, developers and construction companies work for profit, and so cannot play an effective role in addressing real social needs like regional and rural housing, or affordable housing. Enforcing what for economists is orthodox market functioning—supply meeting demand—actually requires favourable tax and institutional market conditions, as well as often socialised risk via government subsidies and incentives. Schemes like the Social Housing Growth Fund mean the government spends money creating attractive investment opportunities for private (‘conscious’) capital it could otherwise be using to actually provide social or public housing instead.

Supply-side propaganda is particularly effective because it seems common sense, and because peak bodies like the AHURI produce a constant flow of sometimes contradictory analyses and policy recommendations (like the constant to–and–fro about wages and profits). If one report claims that the responsiveness of supply to demand (generated by price signals) is ‘inhibited by the availability of sites and the development approval process,’ another more circumspectly suggests that the focus on new approvals and supply is premised on the assumption that ‘more must be good’ [and suggest instead that] a broader perspective is warranted to address the structural impediments that weaken the ‘trickle down’ impact of new housing supply.

The absence of the mythological phenomenon known as ‘trickle down’ is made obvious by the fact that planning policies only restrict development ‘if they have a negative impact on revenue’ and that developers tend to tend for ‘mid-to-high price segments’ without any change in affordable housing.

Supply-side reasoning also licenses the view that landlords and ‘property investors’ have a role to play in providing capital for the housing market, with Richards warning in the AFR that ‘we should be wary of excessively demonising property investors.’

The ideological role of the economics discipline is to defend the legitimacy of profits on capital. These arguments tended to pretend that capital played a role in productive investment, but rent (and other financial speculations) have no such legitimacy. Explanations for rises in rent essentially boil down to the amount of legally sanctioned power landlords have to extract earnings from renters under perceived market conditions.

It is what FTC Manning calls the ‘monopoly over land’ in the hands of the wealthy that determines renting conditions. Manning posits two camps in the housing debate: pro-development, free-market thinkers defending deregulation to balance supply with demand, and social-justice nonprofits and activist organisations

who fault improper regulation and enforcement of rent-control law as the cause of the rising rents and dwindling affordable housing stock. On this account, the construction of market-rate housing only makes the problem worse, and the solution to the housing crisis is tighter regulation, better rent control and the construction of more low-income housing.

Manning highlights the necessity of a class-sensitive analysis, fine-grained enough to recognise that certain industries might experience wage rises while others stagnate but all renters ‘must deal with the same rising rents. The burden thus falls unevenly.’

Notwithstanding growing class-consciousness among renters, such as through the Renters and Housing Union, there is an attitude of resignation among the technocratic policy elite, with policy documents conceding that the

private rental market is broken. Government is powerless to intervene and deliver more supply. Government is almost totally reliant on market conditions improving and attracting new investors to ease the rental crisis.

One de-regulatory avenue often touted as attracting investors is liberalising rent-to-build schemes for financial investment, which would even more effectively embed housing into the pool of crisis-prone financial assets. Current tax impediments to Real Estate Investment Trusts, for instance, are barriers to capital accumulation that supply-side cheerleading attempts to undermine. Richards admits that we should deregulate ‘regardless of whether the benefits in terms of affordability are significant or only modest.’

Housing built under an affordable build-to-rent scheme in Victoria, which uses aggregating thresholds like rent 10 per cent below median rental price and capped at 30 per cent of income, divided prospective tenants in troubling ways reminiscent of ‘deserving poor’ rhetoric. Under the cover of a ballot, rather than needs-based assessment, the scheme claimed to be fair. But after the ballot, applicants were screened using opaque rental tech company ‘Snug’ to ‘score’ them, including ‘giving them a higher score when they offered to pay more rent.’ This compounds issues of discrimination faced by disabled, older and LGBTQIA+ people.

The rush to fill the supply gaps, especially alongside deregulation, tends to erode the quality of homes not just in terms of materials and other safety matters, but also in terms of location. Greenfield developments have been left stranded by the lack of infrastructure and services as developers constantly push on the outer boundaries of cities.

The perpetual frontier of new land release is a strong component of the supply-side campaign. Land is not something that can be produced easily, yet one report insists that ‘governments need to ensure an ongoing supply of development-ready land.’ This is music to the ears of pro-business press, with Richards writing that local councils should be ‘required to ensure that there is a certain amount of development capacity available at all times.’

This approach to land availability is immersed in the future-leveraged world of financial speculation, which constantly pushes the moment of actually addressing the issue of social need into a future in which capital has been adequately unleashed on the problem. This orientation is obvious in the practice of landbanking (which, as the AFR reports, industry groups deny). Cameron Murray’s research and submission to the 2021 Inquiry into Housing Affordability and Supply in Australia details the practice, in which developers hold sites off the market to ‘improve returns and achieve and maintain an optimal pipeline,’ as one company director quoted by Murray admits. Yet when it comes to reporting, the Australian Financial Review blamed planning approvals instead.

By presenting local councils—and cunningly shaming two very rich ones specifically—as the obstacle, as well as presenting prospective residents (never mind that they too are people who can afford to live in Mossman) as powerless against the monopolistic government, the supply-side reaches its anti-democratic apotheosis. At precisely the moment that the housing crisis has caused centre-left parties and think tanks to begin proposing price controls on rent, and calling this ‘a democratic question rather than an economic one,’ the financial world is working to insulate itself from democratic control. Indeed, it is proposing to take ‘powers out of the hands of local councils,’ as Richards writes.

In exemplary fashion, CIS economist Peter Tulip is quoted by John Kehoe in the AFR claiming that the best way to avoid developers trying to influence local councils is to make the planning process more technocratic. Supply-side progressivism also has a tendency towards command-and-control proposals modelled on Singapore’s Housing and Development Board, but with concessions to private capital. Policy recommendations are redolent of resignation to the economic resources developers wield. For instance, despite recognising them as ‘profit-maximising agents’, the AHURI proposes the need to ‘cross-subsidise affordable housing through additional development rights.’ The problem is taking with one hand what the other is giving.

Introducing democracy into the planning process would very quickly illuminate the class stratification in housing and wealth.

The tone of crisis maintains the appearance that only a well-informed technocratic intervention will do the trick, even though what it produces instead are inquiries and reports. MP Jason Falinski, announcing the 2021 Inquiry and pre-empting the conclusion of ‘restrictive planning laws’ and ‘shortage of supply,’ called the problem ‘an urgent moral call for action by governments of all levels to restore the Australian dream.’

The homeopathic restoration to balance of supply and demand operates on crude and abstract market mechanisms with no basis in reality. Concessions to reality in supply-side reporting, like Kehoe’s citation of researcher Ben Phillips’ comment that ‘I’ve seen a huge amount of building, but haven’t seen any great response in lower prices,’ are carefully tucked away before the conclusion offered by Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy that increasing supply anyway is a ‘sensible no regrets’ policy.

The unwillingness to foresee inevitable crises demonstrates the complacency of capital as it seeks new frontiers for accumulation. As Peter Mares observes, ‘Australia’s housing system also encourages a volatile boom-bust cycle of property investment.’

The cycle metaphor is also employed by the AHURI in attempting to deflate the myth of the market’s responsiveness to supply-side interventions in isolation, stating that ‘the supply of dwellings is inevitably cyclical as a result.’ But inevitability conceals the political decisions at the centre of the so-called cycle of crises. Even the OECD, hardly a bastion of socialism, has identified higher taxation as a stabilising agent in housing markets.

Clearly, addressing the financialisation of social needs is the first step in any genuine program of reform. This also means politicising market dynamics beyond the simplistic narrative of supply and demand. It also means democratising planning and development processes as a necessary part of greater state intervention not just in subsidising public, affordable housing, but building or buying and maintaining it.

And if it means bulldozing Mossman, so much the better.

Image: The Sirius Apartments, Sydney. Wikimedia Commons.