At the old Heathcote Mental Reception Home, Martu artist Curtis Taylor installs his art.1 He has erected a bow shelter in the middle of the main room and spread sand and pieces of broken crab on the polished floorboards. Behind a locked door in a white room, he has piled bark on a metal hospital bed. In the flickering light, it looks like piled clothing or shed skin. This place is also known as Goolugatup, and Kooyagoordup. The Noongar Beelier people would come here for the Moondap (blackness of the riverbank) and its excellent fishing. They would gather, camp, initiate men. Then it was a landing site for Captain James Stirling, colonisation base camp, a garden and, for a brief moment, almost the capital city of Perth. Now it’s an old mental institution transformed into a gallery, surrounded by multimillion-dollar riverfront mansions. In the backroom, Curtis has installed a black-and-white film in which he slowly wraps himself, and then a bottle, in bandages while melancholy music plays. The film feels heavy with longing. I stand in the conflicted space uncomfortably realising this place was built for healing. How often do Aboriginal people come to health services for care and instead receive colonisation?

I’m a non-Indigenous healthcare professional who has spent eleven years working in remote Aboriginal communities. It has been a career of having my education and professional practice dismantled by Aboriginal voices. It began with physically bringing down walls, forcing my practice out of clinics and schools and into homes and camps, into red dirt and beside waterholes. But as I spent more time outside my known world, my thinking was also dismantled. Aboriginal people have made visible the assumptions I hold, the rigid beliefs of my profession, the quiet lurking racism. James Baldwin in White Man’s Guilt,2 calls them ‘disagreeable mirrors’, these perspectives Black and Indigenous people hold up to white people, forcing us to confront the possibility we might not be ‘wholly good’. How can that be? Aren’t we healthcare professionals exactly in the business of caring?

I’ve interviewed other health staff working in remote communities as part of a research project. So many of us experience this sudden softening of our moral high ground. The gut-dropping moment when it occurs to us that, despite our best intentions, we might not be doing ‘the right thing’. As one occupational therapist told me, the whole history of colonisation, even the Stolen Generations, has been carried out by well-intentioned people. ‘Spectacularly wrong, but they genuinely thought they were doing the right thing. How do I know my “right intentions” are actually right?’ she asked.

In case you aren’t aware, working in an Aboriginal community proves I am a very good person, an accolade I frequently receive. This is, of course, because of the ‘tragic Aboriginal problem’. The shocking gap in life expectancy. The higher rates of everything bad: heart disease, diabetes, mental health issues, foetal alcohol syndrome, youth suicide. ‘Indigenous’, in health, is synonymous with ‘risk factor’, a perspective basically unchanged since the early days of colonisation. Blackfellas have always been viewed as tragically weak, diseased and dying out, and someone like me best stay away for their own safety. Same story, different whitewash.

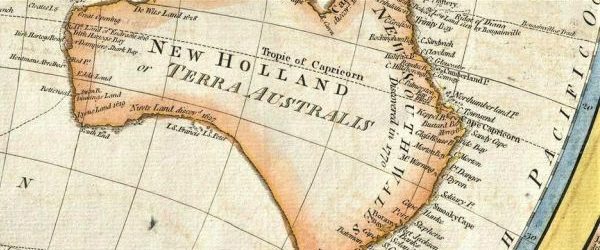

Australian health care has a history, and healthcare professionals predominantly repeat the colonial story, even if its roots are forgotten. Warwick Anderson, in The Cultivation of Whiteness, explores how British doctors, when they came to Australia, were fearful of their new environment.3 Would it be too hot? Too dry? Or in the case of the tropics, too damp? Could British bodies be healthy in this place, or would the next generation grow up sick and stunted? The fear of the unfamiliar shaded medical views, especially those of Aboriginal people who were viewed as diseased and a source of contamination, as a risk from which white settlers needed to remain separate and distant for their own good. Aboriginal people were positioned as a threat, despite the overwhelming evidence of introduced diseases influenza and smallpox decimating Aboriginal communities. Medicine was thick with attitude: disgust, fear and white superiority.

Recently, I visited a remote-clinic nurse to deliver an invite from Martu families to spend time on country with them. He agreed but wanted to use the opportunity to deliver some health education. I asked what topic was his priority. ‘Hygiene,’ he answered without missing a beat. My throat constricted. ‘Do you mean …’ I hesitated, wanting to rescue the conversation from the murky territory it had swerved into, ‘… skin diseases?’ I was thinking of the ringworm and boils I struggled to fend off out here, where desert air dries the skin into paper that snags daily on spinifex and then festers. ‘Washing,’ the nurse replied, ‘the importance of bathing.’ Medicine is still thick with this attitude.

We didn’t take the nurse out with us on country. Instead, women loaded kids and art supplies into LandCruisers and headed to a waterhole. They rolled out a canvas and collectively painted where we sat. A three-year-old leant back-to-back with her grandmother, flicking water messily over the canvas while her grandmother painted. An adult daughter cradled a sleeping infant in her lap while she painted. A calm came over the group. The women sang along to music by a local band pumped out of a phone: Oh, we’re living in the desert, we are the people from this land.4 The baby woke and clapped her hands. Grandma pinched her cheeks. Over the following week, the generations worked together on the canvas, telling the stories of that place. I wished the nurse could have seen. Stories matter, and too often in health we’re telling terrible ones.

It isn’t only overtly racist views tripping up health professionals. It’s the invisible web of whiteness wrapped like gladwrap all through the health service. When I interviewed non-Indigenous health professionals, most of them defined their cultural background as ‘normal’, ‘Australian’ and ‘not having a culture’. The problem with that is we most certainly do have a culture, and we have the power of every Australian school and university, every political institution, the justice system and the health services to enforce that culture. White culture remains invisible to us; things are just ‘the way they are’, it’s normal, it’s common sense, it’s ‘best practice’. I ask allied health students coming into remote communities to break down what an initial paediatric assessment involves. A referral for a recognised developmental delay, a scheduled appointment, an interview between the parent and therapist about developmental history; a series of tests involving the child completing games, puzzles, reading, writing, cutting and talking with the therapist. Then I ask students to examine how each one of these elements represents culture: culturally agreed-on developmental norms, understanding of time, roles of ‘therapist’ and ‘patient’, how personal information is shared in this context, how a child plays and interacts with an adult stranger. Still, when Aboriginal families don’t attend appointments, health professionals often say they’re ‘noncompliant’, ‘don’t get it’ and ‘don’t value their health’. This is whiteness: we do things the way we do because it’s ‘normal’. And anyone who doesn’t fit that norm? That’s on them, it’s not on us. It’s never on us. We’re providing evidence-based health care after all. It’s ‘best practice’. It’s culture-neutral, because if you don’t name the whiteness, then it isn’t there.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about legacy. The British came to an island. They took over the land. They massacred, stole children and dislocated nations of people. Descendants now live out that legacy. Aboriginal descendants, but also settler descendants. One side of that shared history is trying to not talk about it. We pull up a thick blanket of denial. It isn’t exactly ignorance. It takes effort to ‘not know’. Aboriginal people have been speaking up. From the beginning there was resistance. Then there was the tent embassy, activists, letters to the Queen. Now, there’s the Uluru Statement, there’s Aboriginal politicians, educators, truthtellers. Still, when I speak with health professionals working in remote communities, they describe a moment when the not-knowing breaks. Somehow, until stepping into a remote Aboriginal community, they have avoided knowing. Antiracism educator Megan Boler, in Feeling Power,5 describes this denial as a ‘twilight zone’, a space of neither knowing nor ignorance; a hazy, lethargic mist, covering up feelings of powerlessness. Boler’s description suggests non-Indigenous Australians minimise things like colonisation because we’re overwhelmed by it and have lost our sense of agency to create a different world. This description aligns with dissociative responses to trauma: the checking out, the fuzziness, the haze cushioning awareness from reality. Which returns us to legacy. Colonisation traumatises. Not only the colonised but the colonisers. It is traumatising to massacre, to brutalise, to be a witness. How did it effect settler families to absorb these heinous acts? Were there tense silences in households? Irrational rages inside families? Numb or emotionally absent parents? Odd omissions in family stories? How were these gaps folded into communities, the missing chapters passed from one generation to another? Were they passed as tension suddenly rising in the room when certain topics were broached, until we learned to stop raising them? Is it the same tension that still rises now in a room of white people when I mention the word ‘racism’? How did we learn to maintain ignorance in the face of all the evidence?

It’s an intractable thing, this slippery whiteness; the creeping colonisation habituated into the ways health services operate. Habituated into the ways we care. As I watched Curtis Taylor wrap his body in bandages inside those white walls of Heathcote Hospital, I wondered how many Aboriginal people come to health services at their most vulnerable, needing care, and encounter the sharp edges of our health system’s whiteness? Many—according to all the research and everything Aboriginal people keep saying. Slowly, healthcare policy and practice guidelines are shifting. Now, at every national, state and territory level, health services explicitly list racism as a priority concern. Health professionals are instructed to identify and dismantle racism, both in individual behaviour and institutional processes—though most professionals I spoke to were unaware of this. My concern is how? How do health professionals decolonise health care?

Educators of antiracism and decolonisation frameworks across the globe have described this terrain as volatile and emotional. Psychologists and psychotherapists have begun to frame whiteness, and white supremacy, as intergenerational trauma: power dynamics, internalised dominance and dehumanisation, passed down through the generations, even if we’re not explicitly aware of where these attitudes come from. Implicit bias is laid down during infancy in procedural parts of the brain outside our conscious awareness. Sensorimotor psychotherapist Pat Ogden6 explains how babies learn their movements in the context of social relationships. They learn whether it’s safe to reach out, based on the reaction of their caregiver. They learn whether it’s safe to relax their body, or whether they should tense up, based on the reaction of their caregiver. Then these reactions are moved into automatic parts of the brain. We don’t need to think about whether to recoil from a hot stove. Nor do white people have to consciously consider whether to tense their body around an Aboriginal person. The tension simply creeps in, accompanied by fear. The legacy of racism and colonialism is laid down deep, not only in culture and society but in bodies and brains. It shows up in the tension on faces, in the instinct to cross the road, in a tone of voice. Every day we redraw the frontlines of colonisation as we move our bodies through the Australian landscape. Emotion accompanies every movement, a quick, unconscious judgement.

Sparked by observations of my colleagues and students and their intense emotional reactions to work in Aboriginal communities, I embarked on research to understand and map the emotional aspects of racism and antiracism. Denial, anger, fear, guilt, shame, repressed disgust, a crisis of identity and belonging—the emotional reactions triggered in antiracist work are a tsunami.

Emotions flood discussions about racism and colonisation and derail efforts to analyse and dismantle discrimination. ‘I bristled when I first heard those words—dominant culture, white privilege,’ one speech pathologist told me. ‘I remember thinking, that’s not me. I don’t act on my privilege, and I’m not dominating. It’s too confronting and we all walk away from it, which is what I’d done.’ She isn’t alone. Denial, anger and walking away are well-documented responses of white people confronted with racism. Other health professionals I spoke with reported guilt and shame so overwhelming it left them teary, exhausted and useless at their job. Others reported going into hyperdrive: working, reading, studying at all hours, trying to find out how to fix things—‘A whole lot of running on the spot’, one occupational therapist described it as. African-American philosopher George Yancy7 calls this a ‘failure to tarry’, white people trying to rush over the pain of racism into the relief of solutions. The intensity of the emotions that arise when white people finally turn to look at colonisation and racism can make us feel like we’re in a life-and-death situation. Every health professional that I spoke with used the term ‘overwhelming’. As Rachel Ricketts reminds us in Do Better,8 we need to remember that the actual threat remains directed towards Aboriginal people, but still, a real obstacle remains: strong emotions are causing non-Indigenous Australians to avoid reckoning with colonisation.

Robin DiAngelo, author of White Fragility, calls this ‘racial resilience’.9 White people are not used to talking about race and don’t have the tools, the language, or the tolerance for the discomfort and tension. White people have the power to avoid conversations about racism, so when we feel uncomfortable, we simply leave the discussion. Because we avoid the conversations, we don’t learn about racism, and therefore, we fail to deconstruct the injustice–that’s assuming we’re even prepared to deconstruct a system we benefit from. What’s missing from the professional guidelines and workplace policies like the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan,10 which urge professionals to ‘identify, prevent and reduce individual and systemic racism’, is an understanding of the emotional, unconscious, intergenerational nature of racism. We can’t simply educate our way out of white supremacy. University educators who are trying, like Martin Nakata, Aileen Moreton-Robinson and Jon Bullen, keep writing about the emotional landmines blowing up their classrooms. We need to better understand how emotions underpin and perform racism, and we need to find ways to grow white racial resilience so everyone can show up for the process of decolonising.

It’s very tempting to want to tell white people to get over it and get on with it, especially, as Layla Saad11 puts it, when ‘the real trauma, the real violence—death, rape, murder’ is happening to Aboriginal people. Telling white Australians to ‘get over it’ would be consistent with our colonial stiff-upper-lip inheritance and Australia’s general trend of having the emotional intelligence of a brick, but it would also grossly misunderstand the problem. Antiracism educators Cheryl Matias and Michalinos Zembylas12 argue that people need space to unpack problematic racial views, otherwise they remain repressed, packed in tight, impossible to understand and shift. Matias and Zembylas call for ‘strategic’ or ‘reconciliatory’ empathy: holding a space that cares for the emotions white people are feeling without having to agree with their views. I’ve accidentally been misquoting this as ‘radical empathy’. Of course, it’s tempting to jump down the throats of people expressing racist views. It’s tempting to do the same with my own sneaky racist thoughts. It is radical, and uncomfortable, to imagine meeting racist views with care—uncomfortable for everyone, but impossibly unfair to ask of Aboriginal people, whose lives (and deaths) are impacted by racism.

Doing so, however, is sensible if we consider how human beings learn to regulate emotion. We do so in relationship with others. Infants learn how to make sense of feelings and soothe their nervous systems back into equilibrium only in the calm and caring embrace of a caregiver. This need remains in adulthood for all emotions that are too new, or too overwhelming, to make sense of. Colonisation and racism are patterns of behaving, thinking and feeling that go back generations. Our parents haven’t taught us the skills to unpack them. We haven’t brought those feelings to light and had them move through our nervous systems like a storm passing. We haven’t learned how calm returns. Humans learn that feelings are safe to feel by being empathised with and cared for while we feel them. Radical.

Racism is largely understood in what Robin DiAngelo calls the Good/Bad Binary. Good people are not racist. Only bad people are racist. The problem with this construction is that when people come to recognise that racism has been ingrained in all of us, it threatens white people’s moral sense of self and floods us with guilt and shame. How valuable, then, to have a caring person hold us with their attention, a patient presence and loving gaze as we unpack all the ugly thoughts and fears we inherited. Perhaps this is work for non-Indigenous Australians to do with one another. A speech pathologist reflected on how I’d played this role for her: ‘You’d been where I’d been,’ she said, ‘you could translate the experience I was having. It’s the translating that allows you to confront the frailties in yourself that you don’t want to see. It allows you to confront them and see it as a growth opportunity rather than as a criticism of yourself.’ We need non-Aboriginal Australians to respond to the difficult mirrors held up by Aboriginal perspectives as growth opportunities.

American psychotherapists Pat Ogden and Resmaa Menakem,13 have turned their attention towards privilege and oppression and explicitly teach white people how to increase racial resilience. Ogden encourages white people to pay attention to physical sensations like sweaty palms, longer or shorter eye contact, more blinking, frozen smiles, tightness in the chest, or changes in thinking and behaviour like trying to minimise difference, fixate or overcompensate as warning signs that unconscious bias has activated. She frames these symptoms as a learning opportunity, something to turn towards to uncover the racism woven into our bodies and brains. Both Menakem and Ogden teach ‘pendulation’, a technique from trauma therapy, of taking just a little mouthful of an overwhelming emotion before drawing the attention back away, towards a safe, calming other, or self-soothing strategies. Little by little, we can grow our ability to tolerate the discomfort of the feelings, whether it’s anger, fear, guilt or shame. We can learn to tolerate the feeling long enough to unpack and understand where it comes from. Long enough to hear out an Aboriginal person talking about racism. Maybe we can learn to tolerate the discomfort long enough to decolonise.

There are better voices than mine to revision a decolonised healthcare service. Judy Atkinson and the other incredible women running We Al-li Cultural Informed Healing Foundation come immediately to mind. As do voices like Helen Milroy, Tracey Westerman, Bronwyn Fredericks; organisations like the Healing Foundation, Lowitja Institute and Aboriginal-controlled health services. There’s also nangkari and healers in the desert, collecting medicines, wrapping babies, practicing marpan to lead the way. There is a wide web of possibility for health services to lean back on when we’re ready to listen.

Instead, I want to talk about power imbalance, and how it operates to shut out Indigenous voices. Our Western medical model, still dominant in health care, structures everyone into a hierarchy. Medical officers over registrars. Doctors over nurses. Professionals over patients. Power is so much a part of how our health system functions that we rarely stop to examine what it means for a professional to have power over a patient. When a professional is positioned as an authority figure, what steps do we take to ensure the ‘patient’ isn’t repositioned in the opposite direction—to the position of having no knowledge and not knowing what is good for them? How do we make sure ‘I know more about diabetes’, specifically, isn’t blurred into an overall attitude of ‘I know better’, or even more slippery, ‘I am better’? Especially when we add in the additional crown of power: whiteness. Does care, served up with a power imbalance, really feel like care?

Matias and Zembylas explain how some expressions of care actually communicate racial disgust. Disgust is a recoil response, away from a perceived contaminate. It’s commonly observed in interpersonal reactions between different races, but because they’re not socially acceptable, expressions of disgust are often repressed. If you examine some performances of ‘care’, however, you can spot the same recoiled stance, the same distancing behaviour. In the Aboriginal communities I work in, it’s normal for non-Aboriginal staff to keep their distance from Aboriginal people outside work. They drive to the clinic, work, then drive home to the single street where all the non-Aboriginal staff live. Staff rarely have Aboriginal friends. There’s a physical distancing in this behaviour, but there’s also a relational distancing: keeping things professional. I believe the power imbalance in health keeps staff a ‘safe distance’ from their Aboriginal patients. Care is delivered from the high pedestal of ‘evidence-based practice’ that fails to grapple with cultural difference in any meaningful way. Services are delivered in English in ways mostly unchanged from any other clinic in any other part of Australia because the alternative would require a more reciprocal dialogue with Aboriginal people. Conversations that would reposition health professionals as students, rather than teachers. Conversations that would bring them closer to the communities they work for.

I interviewed a physiotherapist who had moved out of public health into a non-government organisation that allowed her to work in radically different ways. She described visiting Aboriginal families with disabilities with her son in tow. They’d go for a drive, go fishing and look for turtles. They’d cook a meal together and the kids would play. She didn’t take her physio checklist. Instead, she might notice how someone was struggling to walk over the uneven rocks or hold their fork as they dug into potato salad. ‘It’s like a friendship now,’ she told me. ‘I’ve had two missed calls from a mum during this interview, and I know she’ll just be calling to check up on my son because he’s been sick.’ In her description, the physiotherapist is in close with the families she works for.

A psychologist I interviewed told me another story. ‘There had been a terrible suicide,’ she said, ‘and there was a whole group of women coming. They were sweeping. They were doing the grieving, you know, they sweep around the place, and they came over and when they saw us their eyes lit up. They came over, and we hugged them, and they hugged us and that was just so … At the very depths of despair, you get this reward of human contact. Because it’s real.’ There is no distance in the psychologist’s story. Not in their gaze. Not in their hug. Not in the human connection in the depths of despair. I imagine those sweeping women felt care.

Both these health professionals delivered their care outside clinics and hospitals. They had proactively reduced the power imbalance and were learning, up close, from the Aboriginal people they provided health care for. The ‘professional distance’ had narrowed.

Colonisation is much closer than non-Indigenous Australians like to think. It’s wrapped in our health service; it’s wrapped in our relationships. It’s wrapped into our emotions, our bodies, and our brains. Decolonising is a very personal business. It cuts in close to our sense of self. Who are we as a nation if this is our history? Who are we as people if this is the current state of things? How can we be good people in the light of this difficult reality? I think the psychologist I interviewed has the hot tip: at the very depths of despair, you get the reward of human connection, because it’s real.

Telling the truth about our colonisation, past and present, allows settler Australians to connect again with what’s real, and with Aboriginal people. It isn’t easy. It will take new emotional skills our parents, and their parents, were unable to teach us. It will take care, instead of colonisation.

Endnotes

1 C Taylor (2021) Inside out, Heathcote/Goolugatup, Applecross.

2 J Baldwin (1964) ‘White Man’s Guilt’, Ebony, 20, 47–48.

3 W Anderson (2003) The cultivation of whiteness: science, health and racial destiny in Australia, Basic Books, New York.

4 Track 11, Punmu Lakeside Band, Punmu

5 M Boler (1999) Feeling Power: emotions and education, Routledge, New York.

6 P Ogden (2021) The pocket guide to sensorimotor psychotherapy in context, WW Norton and Company, New York.

7 G Yancy (2015) ‘Introduction: Un-Sutured’, G Yancy (ed), White self-criticality beyond anti-racism: How does it feel to be a white problem, Lexington Books, London.

8 R Ricketts (2021) Do better: spiritual activism for fighting and healing from white supremacy, Simon & Schuster, London.

9 R DiAngelo (2018) White Fragility: Why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism, Beacon Press, Boston.

10 Department of Health 2013, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013–2023, Australian Government Publishing Services, Canberra.

11 LF Saad (2020) Me and white supremacy [interview], retrieved from: https://omny.fm/shows/sydney-writers-festival/layla-f-saad-me-and-white-supremacy?in_playlist=sydney-writers-festival!podcast#description Sydney Writers Festival, 16 July 2020.

12 CF Matias and M Zembylas (2014) ‘When saying you care is not really caring’: emotions of disgust, whiteness ideology, and teacher education. Critical Studies in Education, 55(3), 319–337.

13 R Menakem (2017) My grandmother’s hands: racialized trauma and the pathway to mending our hearts and bodies, Central Recovery Press, Las Vegas.