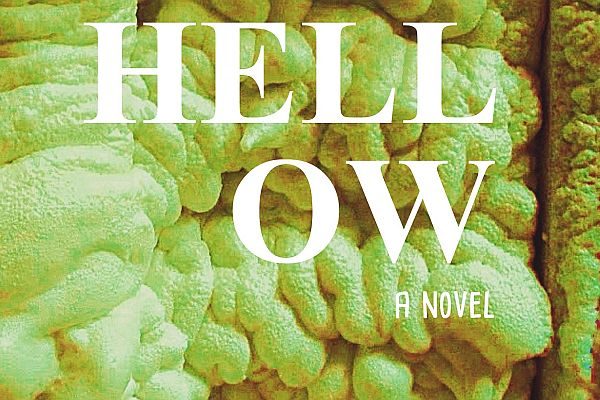

Judyth Emanuel’s Yeh Hell Ow (Adelaide Books, 2019) is a work of suburban (high) modernism, a successor to Joyce, or Woolf and worthy contemporary of Eimear McBride and Claire Louise Bennett, transplanted into tropical suburbs and surgically given a new tongue. It is a novel that plays on the unsteady, even drunken relationship between sound and meaning (and colour: yeh hell ow…), and the equally unstable relationship between what we think and what we say.

Kylie Tennant, writing to Martin Boyd in 1964, recounted that ‘Australia [is] cursed with the most vicious and intolerant set of critics that any country [has] to endure.’ Perhaps this is why Australian publishers failed to adopt a novel like Emanuel’s, and why so few literary publications have reviewed it (although Michalia Arathimos alerted me to the book in Overland).

Among recent Australian novels, Yeh Hell Ow comes perhaps closest to Jack Cox’s Dodge Rose (2016). But the prose in Dodge Rose was restrained … even constrained … even retentive. It says: ‘not bad but commas everywhere like fingers in the cake mix.’ They share a fundamental range, however, an insistence on the availability of all speech, a commitment to the page: ‘now we have all the words.’ This is both the singular value and ‘misfortune’ of modern literature, as philosopher Jacques Rancière describes it in Mute Speech (2011), ‘to have only the language of written words at its disposal’, which ‘obliges it to the sceptical fortune of words that make believe they are more than words…’

The philosopher Jennifer Nagel in Melbourne last year argued that much of our cooperation about knowledge was constituted by communication through ‘epistemic backchannels’. These backchannels are held open by the sounds we make in between our words, like ‘yep’, ‘yeah’, ‘umm’, ‘ahh’ and ‘erhh’. It’s the linguistic version of saying that we ordinarily learn a lot about each other through our bodies.

Then Emanuel steps in and challenges us again: ‘This, I thought, was what not making sense was about.’ It is not necessarily a negative challenge or affront, however. In fact, the narrator’s speech is delightfully diverse: ‘I smile and spoke clearly at various derangements.’ Occasionally, it sounds as though the narrator, Shipley, is addressing us, the reader. ‘Morbid, more trash talking, so deal with it…’ My pulling phrases out of the book feels illicit, since Emanuel’s prose is a visceral topography of sound and words.

While Cox seemed to invite high literary comparison or philosophical elucidation, Emanuel doesn’t so much discourage as forbid it, eruditely and allusively. If it were so simple – which it is not – I would call the second half of the novel a parable of the over-eager critic, parodied from within a novel in constant escape of convenient sense.

First, there is the sound of the novel, its deep (un-clichéd) embodiment. ‘She activated her mmmms’; ‘ummamumama suss-pish-oss minds.’ Italian feminist philosopher Adriana Cavarero writes, in For More than One Voice: Towards a Philosophy of Vocal Expression (2005), ‘the feminine song does not celebrate the dissolution of the one who hears it into the primitive embrace of a harmonic orgy; rather, it reveals to the listener the vital and unrepeatable uniqueness of every human being.’

The world Shipley inhabits, however, is intent on neglecting if not outright curtailing this ‘unrepeatable uniqueness’. But, Emanuel seems to warn, so too is the critic intent on cutting the text down to review-size.

I laughed etc etc. Et Cetera firmed criticalings … Et Cetera me etc etc etc nightmare ogre lorry in the bed running me over splat. With such criticism … Et Cetera me etc so small the size of a word on the page of a paperback …

The critic is, dare I say, personified by the psychologist, who steps in mid-way through the novel to curtail the outbursts of (il-)language. The psychologist performs two functions: dissection of the ‘various sectioned bits’, and attempting to introduce a device for ‘human elucidation’ called the Luci-D.

Luci-D (later simply Lucy) represents the dream of absolute psychological transparency (and control), which ‘processes your documents by transforming the genetic constructs of temperament into the form of an emotional control pellet.’ The psychologist’s speech and prose jars against the lugubrious breadth of Shipley’s errant vocabulary. To Shipley, it is a nightmare: ‘Hello? Rules. I must ignore passions. Tweak. And erased infatuations. Safety faded to a safe space.’ It is as though the device were trying to re-shape her identity into the ‘Holes of me.’

As the novel is slippery, escapist and noisesome, so the attempt at criticism might seem sharp, repressive and like a form of entrapment (or more equivocally, captivation, to cite Rey Chow). The critic is parodied for their misguided organisation of a text: ‘“Find a beginning. Get to the middle. Stir the harking surroundings.”’ Yet it is impossible to do with Yeh Hell Ow.

Reading it, I could relay to you dim, over-saturated, Vaseline-smeared glimmers of a setting – a suburban area of a major city, perhaps Sydney (or did I just read Emanuel’s website, which in that strange habit of erroneously wordifying URLs I always read as judy-the-manuel.com), sun-soaked (why? Perhaps the constant yellow glint), and infused with globules of a viscous yellow membrane. The characters: Shipley, her friend Alison, some older, more benevolent types, the psychologist (Geraldine Burrows) and an array of leering men, always on the edge of violence, who speak with a sort of venereal sneer.

However, like Eimear McBride’s implosive A Girl is A Half-Formed Thing (2013), all this comes at goes at the behest of the language and its construction of a unique encounter between a newly-formed, shape-shifting mind, and a somewhat hostile, forcefully sensuous world. What matters is what she thinks, and, moreover, how she thinks it.

The sociologist Eva Illouz, in Cold Intimacies (2007), characterised our contemporary mindset as one of ‘a hyperrational fool’, ‘somebody whose capacity to judge, to act and ultimately to choose is damaged by a cost-benefit analysis, a rational weighing of options that spins out of control.’ Emanuel has Shipley describe herself as ‘The perfected fool. My hearted and minded faced the excruciating, the obscure, the intangible, the impractical. The perfect fool ignoring the obvious, the prudent, the premediated. The perfection fool lacking respect for rationality. Logic killed the jack-in-the-box.’ Shipley is the Don Quixote to Flaubert’s Bouvard and Pécuchet, addressing the criti-cum-fool as that renowned knight errant does, ‘“So you must not be distressed about the misfortunes that I undergo, for you have no part in them.”’ The critic rather follows along, historically behind wishing ‘to have the faculty of rumination’, as their heroes so often seem to do, or ‘hoping to make great discoveries, and made none, which astonished them greatly.’

It is the critic’s job not to be surprised by whatever startling inventiveness appears on the page. At least, if they are surprised, they must perform the critical manoeuvres that explain both to themselves (to save their critical authority) and their audience (who may or may not buy a book on their judgment) what the book means. They must place it in a context, subject it to our prejudices and neatly summarise its main themes. ‘“Was the session worth it?”’

Yet all this treatment, what does it achieve? The critic is advised by their mouthpiece, the psychologist: ‘“This process builds the fortitude to become a false individual. Yes. Fakery is the treatment.”’ The review is a fake; its version of the book is like the psychologists version of Shipley, ‘dishevelment of the inexplicable.’ Shipley outruns the psychologist in a specifically mouthly way, as the philosopher Monique Roelofs might say. The psychologist ‘listened but but failed to perceive. Urk death to perception … Her enamel disinterested in me the duckling.’

According to Psychology Today, Freud theorised that dreaming of teeth might be associated with castration and punishment for masturbation. A kindly nun recounts her conversion as though it was a kind of unifying severance: ‘“I invented my vocation … I prayed to God. Hardly ever. Dear God let me be. Set me free. Make me whole and wholesome. Get rid of this damn hump. Chop off my goblin nose.”’ The nun and Shipley share the experience of violence to which these attempted compressions are a response. ‘“Father O’Brian pushed me into the confessional booth. Drooling. I kneed him in the groin.” Brought him to his knees. Proper genuflection! Ha God bossy said stay on yer knees.’

There is a passage I hardly noticed when I first read it, perhaps from the embarrassment of self-revelation.

He put out his long wedge … Dickie diddler dicked a dot to ditch his doppleganger. Add droned groaning. Me as flat as a stingray on the dormat shore. My heaving ha ha body of ripples. The man made of sand … He nosed in bosom dumplings … Palest rouge nipples shy and luscious pinked at the rims. Deadly as the seafloor. I laughed and laughed.

Yeh Hell Ow can be very funny. Its duration: ‘Liked nothing else in creation.’ Afterwards, ‘Bewilderblissed.’ Surely one of the most scathingly accurate descriptions of aftersex.

The novel keeps on dissimulating. In this sense, it is as self-reflective as Lynne Tillman’s Madame Realism at her most, shall we say, fallaciloquent (Colin Burrows’ invention) or fal-loquacious (my invention, trying to remember what Burrows had said). For instance, in the story ‘Madame Realism: A Fairy Tale’, she ‘couldn’t decide what was trivial, insincere, fake, inauthentic, frivolous, superficial, and gaudy; she herself was all of these.’ Her embrace of these patently manufactured, and often pejorative qualities makes it impossible for her to use those categories to describe others. ‘I am always fiction.’

Emanuel’s novel does the same, ‘Yellow me into a forgery.’ It finds ordinary descriptions of reality so unsatisfactory or unconvincing that it must re-invent them as maxims to practice:

‘Try to think sad thoughts, when you’re sad.”

“I am always sad.”

“And think happy thoughts, when you are happy.”

“I am never happy.”

These kind of ‘harmonious moods’ in which reality and imagination coincide conceal under the guise of a therapy a kind of economic behaviourism endorsed by whatever pharmacopornographic technology is trying to absorb us at any particular moment.

In other words, life lived as a game mixed with schlock body horror under a gauzy layer of depressive realism: ‘To battle evil, unicorny fulfilled dreams desires, communicate awesome urgh. And top notched duelled monsterfish, realm thug, princess snowcone, sonicdash. What The Heck. Where the redbetter douchebag mortal enemy in dancer hoofs nestled in a spellbook. But no. Core Pills immobile in drab. Lifeless. Blame my faulted. Leaden, but it weighs nothing, their grim foretold me ashen. Of impatient.’

I should clarify that I’m not really suggesting that this novel is aimed against the critic or attempts at criticism. It is not didactic in the least, as I hope the excerpts prove, nor does it labour over the conceit I have applied to it. Rather, this conceit offered me a way of showing the breadth of the novel’s ambition, and one among many possible (implausible) critical approaches to it, and prevented me from simply paying tribute to its sonorous qualities. ‘“Mwa mwa mwa. I love it to bits.”’

The narrator’s verbal idiosyncrasy is constantly twisting the everyday from its moorings – ‘On the biggle day’ – and refashioning them so that they are tolerable to her palate. She perceives in ordinary epithets ‘Casual veiled threatenings.’ A monologue starts with some chitchat niceties – ‘“You looky looky fabulous. I told you so. This looks interesting. Thinking of you…”’ – but becomes ever-more demanding, baring the coercive undertone of niceness – ‘“Why haven’t you called? Where have you been? I did call. Let’s go for coffee. What’s for breakfast. What’s for lunch. What’s for dinner?”’

How then could I have accomplished an ordinary review? Instead I have theatricalised my admiration for the novel into an excuse: why this cannot be a review. Returning to my albeit simplistic comparison between the psychologist and the critic, the review must accomplish ‘“The completed you”’ by application of pills that ‘“transform into an imitation of yourself… Get yourself to yourself.”’

The pretension to present a version of the book is parodied by the psychologist’s insistence: ‘“You will become an imitation of who you are purported to be.”’ Novels like Yeh Hell Ow have a hard time in the world. They abrasively resist representation and are defiantly demanding. ‘“Err. Can you define gobbledegook.”’ Recommending them must take place without the conveniently pre-fabricated scaffold of plot, theme, character because these are not what makes this novel what it is. ‘I can’t think of the word of yell reason hell yes ow.’

Judyth Emaneul’s Yeh Hell Ow made me find internal orifices I did not know existed. It oozed through my brain, and sung in the back of my throat. ‘Yellow was here. I named it Yeh Hell Ow. You yell, its hell and cry ow it hurts.’