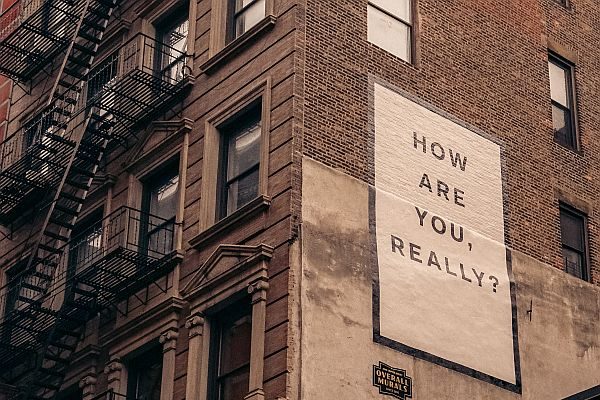

Mental health is in fashion. Countless articles, TED Talks, working groups and corporate PR documents say that ‘We need to talk about mental health’ as if silence were the overriding problem. Celebrities like Stephen Fry teach us that mental illness can affect anyone and doesn’t discriminate, as if it just hit people at random and weren’t a social phenomenon. Using this framework, politicians and corporate heads talk about improving mental health even as they worsen its determinants – poor housing, exploitative working conditions, bigotry – all while slashing the mental health departments at the bottom of the cliff.

In its depoliticised form, ‘mental health’ can be used to explain just about anything. Most recently, New Zealand National MP Andrew Falloon was caught sending pornographic images to several young women and invoked his grief at his friends’ suicides as the cause. No one is clear how the friends’ suicides to sending unsolicited pornography pipeline works but, perhaps unusually, this time the excuse failed to work.

On a level, Falloon’s mental health defence was a cover for denying his own agency – one of the mainstays of the abuser’s playbook. Abusers often invoke loss of control to cover up their choice to hurt people: ‘You’re so sexy I couldn’t help myself’ or ‘She just makes me so angry that I lose it.’ It’s funny, isn’t it, that any supposed loss of control always results in very well-targeted abuse to someone with less power than you.

However, mental illness more broadly is a popular excuse for abuse. A little over a decade ago, New Zealand right-wing blogger Cameron Slater described his enterprise as an outlet for managing his own depression. Of course, many of us have experienced the aggressive nothingness of depression without turning to high-level attack politics. But his explanation guilted some people into dialling back condemnation for his behaviour, extending him a misplaced generosity totally absent from his own conduct. While it’s possible to be genuinely mentally ill and an arsehole about it, Slater’s excuse relied on the abuser’s maxim that feelings cause behaviour. If you believe this, at all, think of every time you bit your tongue rather than criticise someone, or refrained from eating a slice of cake. Abusive behaviour is a choice, and abusers can virtually always stop when they want to, or when they fear the consequences.

Last week, shortly after her inauguration as leader of the National Party, Judith Collins revealed to Radio New Zealand that over the years she had come to realise the importance of mental health. Simply uttering the phrase ‘mental health’ can apparently dazzle people into thinking you’re speaking in good faith, seeing as her interviewer failed to remind Collins of the major damage the National Government (of which she was a member) caused to the mental health of New Zealanders. Gutting the health sector, increasing poverty through draconian benefit cuts and union-busting, and deregulating the housing market all contribute to mental illness and suicide rates.

While Labour supporters might like to crow about National’s hypocrisy here, Ardern’s government is not without fault in this arena. Besides critical issues with the ‘wellbeing’ model and the troubled implementation of mental health reforms, there is little mainstream recognition of the trauma inflicted by a government that empowered armed police to terrorise Māori and other people of colour, or permitted landlords to raise rental prices sky high. At best, clinical mental health treatment is a necessary and beneficial plaster on top of pre-existing pain. At worst, it is a tool of traumatising violence used to subjugate people, especially minorities. The mainstream conception of mental health often just means fitting neatly into society, without energy or interest in questioning any form of oppression.

What about the mental health of the women who were abused by Falloon? As anti-abuse worker Lundy Bancroft wrote in his book Why Does He Do That?, abusers are not generally out of touch with their own feelings, but with those of their victims. A societal effort to ‘manwash’ mental health would have us believe that men are suffering more than women, the most commonly cited piece of evidence being that they commit suicide two to four times as often as women. Why do so many people know that statistic, but not know that women attempt suicide at three times the rate of men?

Manwashed mental health also argues that men are emotionally repressed, and that women must help them express their feelings more. In reality, most men are not at all shy of expressing a wide range of feelings to women – including anger, sadness, fear (‘You’re so intimidating!’), jealousy, condescension, boredom, perpetual horniness. Meanwhile, women cannot react in any negative way without having mental illness invoked against them. ‘She’s crazy, man!’

Abuse apologia suggests that mental illness creates bad behaviour. I’d counter that an abusive mindset can create and sustain mental health problems. This doesn’t mean abusers suffer the way victims do; ‘This hurts me as much as it hurts you’ is a dangerous lie. However, an overly-entitled mindset can create rage issues, paranoia, jealousy, and negative behaviours that lead to broken relationships and long trails of misery. Contrary to what people like Falloon would prefer, these problems aren’t solved by soothing words and affirming all their actions. If you care about someone, you have to stand up to them when they’re doing something wrong. Stop worrying about powerful people’s mental health, and start worrying about the people they hurt. It would be nice if the Falloon scandal helped New Zealanders see that mainstream mental health discourses are not benign or compassionate. They are ways to keep the powerful comfortable while pathologising the powerless.

Image: Finn