With the mast in one hand, I clutch my last Vegemite sandwich in the other as I search for the island. Squinting through warm spray, I see it rise in the distance, beckoning from across the heaving sea. My replica Viking færing will make it – fashioned from the most robust plastics I could find. Still, as I surge forward and my fingers slip and slide, I wish I’d built in a seatbelt. Swallowing the sandwich, I whip my design pad from its bag and shield it from the spray before adding to my section on improvements.

Water wells up around me and I’m forced to push my fears inside. Rumours of the island are crammed in there, like my memory of Mr Cummins from the newsagency. I’d watched his enormous hands tower above Mum for years, giving her compliments before handing over the paper. One week before I set out, I’d flicked through the latest Injection Moulding World while he gesticulated on the headline: ‘An eighth continent my arse. You’d no sooner set foot on it and they’d cut your bloody head right off.’

Mr Cummins wasn’t the only one with doubts about the island. April at Foodworks told Mum it was where the terrorists came from. (Her kohl-rimmed eyes had narrowed as she whispered while Mum paid for the groceries.) Not only that, she said it was ‘full of disease,’ and that her cousin Ben’s best-friend’s neighbour’s boyfriend caught an unknown virus in a sail-by ‘just because the wind was blowing his way.’

April’s face sloshes about inside me, along with Mr Cummins, her fake purple nails clacking in time to the ropes on the mast as an enormous wave careens the boat to one side. Still, my commitment doesn’t waver. Since hearing about the island on my twenty-first birthday, I’ve known it’s the only place I will ever feel free.

The cobalt water thickens with debris the closer I get, plastics and non-plastics caught up in the suction. I pass other boats, like the ones from the front page of The Herald Sun – the ones we always turn away. Here they look peaceful, at home as they bob and sway and form a fringe around the island’s edge, nuzzling the blue-barrelled cliffs. Still, the threat they are tethered to is one I haven’t properly considered.

A vast encampment – brimming with faces – stretches back farther than my eyes can see. There are no palm trees, only aerials: an enormous tangle that plays host to a symphony of sea birds whose droppings add texture to the flapping Visqueen patchwork roofs below. Along the abrupt shoreline, fisherpeople dangle rods and throw nets beside kelp flags that flutter in the breeze. This breeze carries the smell of storm drains in summer, as well as a promise of something greater.

Rubbing the salt marks from my glasses, I prickle as I am noticed. A robust crowd surges to the edge of the gigantic polymer pontoon and signals for me to moor. I crave the hat Mum knitted me, the one I take to the shops to pull down whenever anyone gets too close, and feel around for it, only it’s no longer there. As I close my eyes, Mr Cummins and April begin sniggering and I bulge on the deck, pushed along every one of my seams.

I’m rescued by the screams of a man – he is topless, ribs protruding – as he is corralled onto a boat by the crowd. Wearing an ankle-length sheet and sandals, he struggles before dropping to his knees. A sack is thrown in after him, and a barrel of water, which makes his raft dip and sway. I watch as they cut his line with a knife that is practically all blade.

The man glides past me, choking black fumes propelling him along. Shaking and shiny-faced, he grabs for me. But, as plastic meets plastic, and my own hull thuds into the hollow shore, I too am thrown to my hands and knees.

A coil of polyamide rope thumps onto my deck (it’s not the strongest but I know it will hold). Above me, a blur of scarves, hats and beards shouts at me – a confounding array of fabrics unlike anything I’ve ever seen. As the colours meld and whirr, I try to decipher each face. But these faces are so different to those on the white flash-cards I’d practised on at home. Eyes seem ‘forlorn’ but the smiling mouths do not match. Nostrils flare but there is laughter. I feel like I’m missing vital cues. Getting each and every one of my answers wrong.

Rocking back and forth on the deck, I am steadied by a long, coal-coloured hand. A deep, booming voice follows. ‘Do not be afraid, my friend. I am Aaden. Welcome to the island.’

Looking up into the man’s enormous eyes, I’m met by a stretch of long luminescent teeth. He pulls me up and, as I stand, the distinct fumes of heated PVC whack me in the face. This is the smell that led me here. The promise I followed halfway across the Pacific. Soothing and addictive, I want more of it. Need to draw it into my lungs and transfer it to my blood. Like a child following the scent of fresh bread to the kitchen, I place my foot onto the shore. My sole embraces the island for the first time.

An electrical surge shoots through me. Everything ripples and I fill with warmth. The island and I fusing together.

Back in Williamstown, I’d never understood when people on the telly spoke about ‘belonging to the land’. I spent a whole afternoon once, face down in Mum’s backyard breathing dust, trying to work it out. But in this very moment I get it. Looking down, I’m comforted by the foundation beneath me – the fusion of fishing lines, netting and buoys. I’m calmed by the millions of compacted milk cartons, coffee-cup lids and water bottles. I am in harmony with the six-pack-rings and intertwining plastic bags. Here, the revolutionary, magnetic clean-seas™ catalyst has done all it had promised and more: cleansed the seas while unifying us here in a singular destiny.

Standing tall, I wobble with Aaden across the enormous plastic flotilla to where a smaller man steps forward to take my other arm. He has cropped white hair and a beard of biblical proportions and hands me a Tupperware cup as he shuffles me along the main street, straight up the guts of the island.

‘Come, friend. My name is Tarek and you must be thirsty?’ he says.

We walk alongside salt-encrusted polypipe gutters full of refuse and grime, which flow in the opposite direction towards the sea. All around us radio signals buzz in and out of range. Aaden smiles at the crowd now following and I make my mouth smile too. Others join our procession from smaller paths that burst in at intervals, streaming from the damp cobbled-together huts and grotty lean-tos adorned with drying fish and plastic utensils.

Walking across the broad field, through the humming tent city, I watch people cook fish over campfires and cast seaweed into pungent broths. Drips rain from the mouldy tarp verandahs, only to be recaptured in colourful buckets. Women wearing long dresses, bright sheets, or what I imagine are pyjamas, hang more of the same on makeshift nylon washing lines while men hammer and tinker with PET bottles, distilling water, and add to the smoky haze with their pipes and cigarettes. And in the spaces in-between there is laughter – the squeals of children who skip around or kick balls made from packing tape. These children stop to stroke my clothes, touch my rayon backpack and ask for sweets. I can’t believe how different they are to the kids back home. ‘I don’t have any,’ I say to them, wishing I’d bought a case-load with me from Mr Cummins’ store.

We pass farmlets of tubbed potatoes fenced in by walls of even more bottles filled, this time, with green leafy vegetables. Queues of people wait for supplies or for access to the polyethylene water tanks where my cup is filled. Heat rebounds from the plastic and I’m again parched by the time we arrive at the centre of the island. Here, the sun is razor-sharp. I swat sweat, blinded by the paddocks of solar panels interspersed with foraging chickens and bleating goats. Hooked up to salty batteries, a young man in loose pants moves between power units with a rag, trying to keep them clean. He greets us like we are important. Wishes us well as we discuss ‘great things.’ He ushers me to the island’s centrepiece where my jaw almost hits the ground.

The yellow and white striped big-top is the largest I’ve ever seen; surrounded by a green of synthetic grass, its smell is distinct from all the other plastics (warm PVC-coated polyester combining with fairy floss and a hint of manure). The walls flap in the breeze, snapping as they bend back and forth. I’m expecting clowns and horses as we enter. To be dazzled by sequined women, or men in top hats and tails. But when we trade the glaring sun for sparkling downlights, we occupy a space meant for a different kind of show.

A tiny woman stands in the middle of the ring, her glistening scarf covering her long, glossy hair. She signals to a milk-crate in the front row and I plonk down on the hard polyethylene criss-crosses. Laid out in concentric circles, more milk-crates stretch to the edges of the big-top. Dyed different colours, they reflect the island – I’m seated on a humungous milk-crate map! And I watch with my mouth still gawping as hundreds of representatives move in to take their places. The doors swing closed and the sounds of camp-life muffle. ‘Welcome to the All-People’s Council,’ is now all that I hear.

Watching the woman speak, I wonder if she is their leader. But even though she’s the only one standing, I feel like I’m the act they’ve all come to see. ‘Where are you from, friend?’ she says, addressing me but looking at everyone else.

The red dot on her forehead distracts and I try not to stare, Mum’s words reminding me not to ogle people who look different. I focus on her coke-coloured eyes as I answer, ‘Williamstown.’

‘Tough place to get into, that one,’ says Aaden next to me, his giant smile still beaming away. ‘Such a pity though. So much potential for great things.’

A murmur swims its way through the tent and I nod, again showing him my teeth.

‘So, you have come here for safety, my friend? Not to be scared anymore?’

‘How could you possibly know that?’ I say.

‘Because we are all essentially the same.’ I swing to Tarek who speaks to the room from a crate on my other side.

This knowledge that they know me is like a punch to the stomach. I’m transported home to the shame of the alleyway where I’m chased every day. I see cans hurtling through the air. Touch the blood oozing from my head, as I’m peppered with rocks. I lie still as my shoelaces are tied together – the same exact shoelaces I’m wearing as I blink and return to the reality of the stifling tent. But these islanders have done nothing wrong. Still the past wavers before me, along with the image of the sad man kneeling in his boat.

‘The man on the shore when I arrived, why did you send him away?’

‘Yusef broke our law and is no longer welcome.’ The woman with the dot has her printed palms out for all in the big-top to see. ‘And if you have the same intention you too must go. But harm no-one and you may stay. Everyone is welcome on the island.’

‘Oh, I won’t make any trouble.’ I say, trying to reassure her. ‘I just want to live in peace.’

There are nods. Even cheers. And Aaden’s enormous hand, again upon my sleeve, gives me the confidence to go on.

‘It’s Hobsons Bay Council, you see. They keep issuing me fines. Threatening me with prison if I don’t do as they say. And Mrs Witten from next door. She was the one who told them my shed was an eyesore – that it doesn’t fit with the local streetscape. That the fumes I create when moulding are ruining the air. She even got the council to make me tear down my very own home!’

For the next twenty minutes, the whole tent listens as I recount my nightmare. I pass around photo albums full of designs. Show them pictures of my bungalow and everything I dreamed it could be. I place the drawings in their coarse but keen hands. Snapshots of my bed, my desk, my drawers – all crafted from polypropylene, polycarbonate, polyethylene and more. But then as I continue, I notice blueprints turned upside down. Frowns replacing nods and my voice climbs a pitch as the fear brigade inside me again begins to shriek.

‘You’re not here to escape persecution!’ shouts a shrivelled greying man from up the back.

‘We could issue him a tourist visa?’ says another.

‘But we are an island for refugees! A last hope for those who have nowhere to go.’

The big-top is seething, my own voice unheard beneath the din. ‘But I don’t want a holiday,’ I say.

There is shouting. Arms flying up, down and about, and I crouch to the floor. Until above my head a loud clap echoes, and I fear the worst.

But only silence follows. The filtered cries of seagulls and young children seep back in. Aaden is standing beside an apple-cheeked girl, her black braided hair held together by an army of flexible silicone ties, as she calls everyone to attention.

‘Be quiet all of you,’ she says, eyeballing them, causing them to settle. ‘It is my turn to speak and I have a question for the man.

‘My brother, he loves football. He looks after my father’s World Cup card collection better than anything else we own. He knows every player, every statistic. Everything there is to know. Are you the same, Mister? Do you know everything there is to know about plastic?’

A thousand eyes drill into me while they wait for a response. I long for my hat. Reaching out for the ground beneath me I find it meeting me back. Then, looking up at the yellow and white big-top, I once again inhale its perfect musty polyvinyl chloride scent.

*

Over at the new dock a boat of American refugees is arriving. As they step onto the floating pier, they stare through the plastic grating into the murky water to where semi-naked divers are busy cleaning buoys. With knives in their mouths, the divers strip the 55-gallon drums of molluscs, placing them into net-bags as they would oranges from a tree. Many of these shell-shocked new faces are like the ones on Mum’s flashcards but from a distance they are still hard to read.

‘Poor buggers!’ says Aaden, holding two sheets of Perspex together atop the workbench while he waits for the glue to set. ‘They look terrified. Not sure whether this place is better or worse than the last.’

Tarek emerges from a large salvage pile where he is sorting the plastic in tangled, soggy nets with the rest of our team. ‘They all know it cannot be any worse than where they have come from.’

These words don’t make the faces any clearer to me. But I know from stories, told by those I build houses for, that what they are saying is true. Switching on the 3D printer, I speak. ‘From the numbers on this boat, one thing is certain. We’ll need the school finished by next week.’

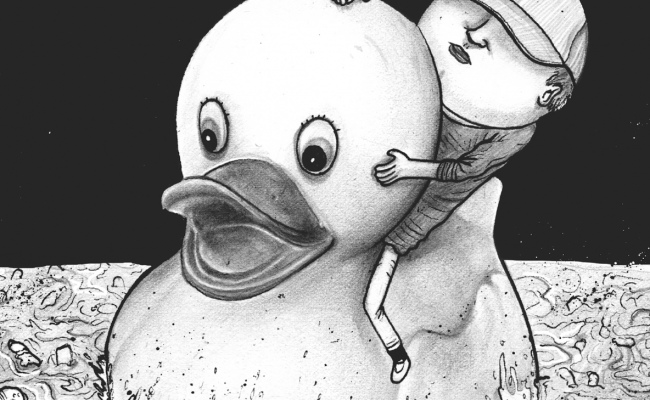

‘And the new hospital wing?’ Tarek’s voice trails off, as he looks back to the lengthening queue waiting at our depot, before disappearing with increased urgency back into the mountain of spare parts. Moments later his hand shoots up holding a bright yellow duck. ‘Look at what I found for the baths.’

We laugh and work, hearing Chanda’s voice in the distance welcoming the newest settlers to our island in her official-sounding tone. Even though no-one is in charge here, she enjoys doing this. Which is good, because our tiny piece of paradise grows in square meterage and population by day.

‘Do you think the island will ever be full?’ says Aaden.

I consider this as I consult the plans. Programming in the piece we most need next.

Read the rest of Overland 235

If you enjoyed this piece, buy the issue