Spray-painted onto the colossal stones of a Parisian building during the ‘gilets jaunes’ protests was a quote from Paul’s first letter to the Thessalonians: ‘And when they say “peace and security”, then the world will be lost.’ If malign calm follows a storm, it is the calm of rubbish piled on the beach, as though the ocean were trying to vomit up its sickness.

Although it feels like we are being flung into the constant storm of climate change backwards, like Walter Benjamin’s angel of history, it is clear what the storm will leave strewn behind, for it is written in policy documents and circulated at conferences around the world. The message is unambiguous: the climate emergency is a threat to national security, and the response of rich nations will be to militarise, protecting themselves against effects they have done nothing to mitigate.

The mindset of militarisation projects the threat of climate change onto other people, thus deflecting responsibility and providing justification for treating others as hostile. Western countries are building armed gunboats for a world in desperate need of lifeboats, with militaries and corporations preparing to profit from the crisis we are facing. When they say ‘peace and security’, Nick Buxton and Ben Hayes ask in their crucial 2016 volume The Secure and the Dispossessed, ‘what is being secured, for whom, from whom, and at what cost?’

Recently I sat, flummoxed, at a conference about ethics and utopia in a glass-walled Melbourne office building as the need for military planning in response to climate change was heralded as simple realism. The reasons offered were that climate change is hard to communicate, and action has been too slow; that governments and conservatives listen to militaries; that if climate change is perceived as a security threat, governments will be compelled to act.

If the discussion stopped there, the conclusion would be that military logic ought to be used instrumentally to achieve necessary action to mitigate climate change. But the sequence continues inexorably, because, in perceiving climate change as a security threat, governments have not responded by stemming its causes or reducing its effects.

Instead, their planning for food shortages, mass forced migration and resource scarcity has followed nationalist militarisation, something we see at work already in Western border security policy. Todd Miller and Alex Devoid attended a conference for In These Times back in 2015 where military and corporate hawks circled over the dying carcass of fair climate action, waiting to provide fire-power to rich nations against the tide of mass displacements. When military logic instigates action, military outcomes result. As Naomi Klein writes in her essay ‘Let Them Drown’, ‘under our current economic and political model, it’s about things getting meaner and uglier’.

It is not only war profiteers pursuing military strategy as a response to climate change. Environmentalists have tacitly adopted securitisation discourse ‘as a means to galvanise the international community towards a conclusive agreement on emission reductions’, Michael Thomas argues in his 2017 book The Securitization of Climate Change. He notes, too, how developing countries were resistant to the rhetoric of securitisation. At a UN Security Council meeting on climate change in 2007, delegates from developing countries steadfastly (if politely, even bureaucratically) resisted the encroachment of security discourse into what they saw as an issue of sustainable development. Egypt’s Khaled Aly El Bakly castigates developed countries for having ‘failed to fulfil their obligation to rectify the situation’. The security debate, he argues, is ‘an attempt by the developed countries to shrug off their responsibilities’.

Backed by military logic, however, a coalition of complicit environmentalists, hawkish governments and greedy corporations have successfully sabotaged any such action. Their ‘one percent doctrine’, examined by Ron Suskind following Dick Cheney’s rhetoric in the War on Terror, means they will act violently in response to perceived security threats but not matters of urgent humanitarian concern or justice. If the 1% possibility of a terror attack is enough to warrant torture, or a drone strike, it seems that no amount of certainty about climate change has warranted sufficient response.

But since at least 2003, militaries have been certain about the imminent effects of climate change, with the United States and Australia leading the way. Their operational guides began to include definitive advice and realistic assessments of the increased resource scarcity and likelihood of conflict and mass migration. These documents tend to focus on the continued viability, for instance, of military bases in the Pacific that are at risk of inundation. Australian and American military installations are particularly vulnerable – and Australia perceives itself as all the more so for its proximity to countries where climate change will have a high impact but the affected country has few resources to respond. We must pay close attention to how this assessment enables what Lorraine Elliott labels an ‘extreme’ response including ‘the application of “fortress” models to protect borders’.

Borders and migration are the most salient examples of the securitisation of climate change. Already, in Australia, the United States, Malaysia and the EU, militaries are being called to police borders under cruel anti-immigration regimes. Yet environmentalists like Phyllis Cuttino of the Pew Charitable Trust still believe that the military will finally convince conservatives of the need for climate action. Cuttino states, ‘If there’s anybody that’s going to be at the forefront of how to save energy, reduce global greenhouse-gas emissions and become more efficient, it’s [the military], because it’s in their best interest … We’re all going to benefit from what they’re doing.’ But conservatives use the military’s advice to call for strengthened borders instead. Former US President Barack Obama made this clear when he told the Coast Guard that, ‘climate change constitutes … an immediate risk to our national security … make no mistake, it will impact how our military defends our country’. Remember: security for whom?

The military garners a new raison d’être from securitisation. Robert Marzec, in Militarizing the Environment, quotes Admiral T Joseph Lopez’s claim that climate change could ‘provide the conditions’ to ‘extend the war on terror’. Climate change is euphemistically called a ‘threat multiplier’; though, as McKenzie Funk, author of Windfall: The Booming Business of Global Warming, puts it, ‘The immediate call is for more urgent action to tackle climate change … the obvious subtext is that the military better get ready and be given the resources to deal with a messier and more conflict-ridden world.’

The subtext has long been evident; writing for the Norwegian Refugee Council in 2008, Vikram Odedra Kolmannskog criticised the way securitisation discourse suggests that poor countries pose a ‘physical threat to the prosperous [nations] by population explosions, resource scarcity, violent conflict and mass migration’. Even the cautious modelling of the Brookings Institution-funded book Climate Cataclysm warns that the EU will ‘retreat behind high walls and naval blockades, a containment strategy that [is] morally indefensible and will provoke tremendous internal unrest and impoverishment, but will also be seen as a matter of survival’.

If conflict in Syria partially had its roots in internal displacements brought about by an extreme drought from 2006 to 2009, as Christian Parenti posits in Tropic of Chaos, then the wave of refugees who reached Europe are among the first mass forced migrations of the era of climate change. Jérôme Tubiana and Clotilde Warin detail the European strategy for treating both refugees and migrants from their southern neighbours: turn them back. This policy has meant colluding with the authoritarian regime in Turkey and funding militias in Libya, who kidnap and extort migrants.

Their militaries are implicated in tight border control, supported by right-wing governments in Italy and further north. European nations also have their eyes trained to the north, where melting ice exposes untapped oil. Arctic Thaw, a book about the race to claim those resources, reads like a bureaucratised Cold War thriller. The situation is perilous, as corporations salivate at the prospect of approximately 90 billion barrels of oil and 488 trillion metres of natural gas to burn for profit, causing accelerated global warming. Gazprom, Chevron, Rosneft and Statoil already hold licences to explore, and Russia, China and the US are armed to defend their share.

The United States is no stranger to militarised borders. There is evidence that migration from Central America is influenced by climate change (rather than the oft-cited drug-related violence). Proposed by scholars as early as 2010, the effects of climate-change-induced extreme weather created food insecurity for millions in Central America, mirroring the situation in Syria but on a longer-term scale. This effect has been decisively connected to the recent surge in migrants seeking better lives by Todd Miller in his 2017 book Storming the Wall. Although climate patterns have long affected migration, the current movements are unique in being a result of human-induced climate change. These migrants also face greater than ever obstacles in the form of militarised borders and racist regimes intent on excluding migrants from White Fantasy lands of peace and security.

‘Just like super-typhoons, rising seas and heatwaves, border build-up and militarisation are by-products of climate change,’ Miller writes. We should not overlook the brutal and racist policies of the current Trump administration as a defining factor in the increased securitisation of the border. But the military’s worldview puts migrants under the category of ‘threat multiplier’, and replaces the shared dangers of climate change with the external danger of forced displacement. Crucial to the securitisation of climate change is the externalisation of the threat, as Hayes argues. Security casts the threat that fossil-fuel-based capitalism poses – both to itself and to others – exclusively onto foreign bodies.

The US military’s sinister calculation is that climate change will hurt others more than it hurts them. The Pentagon ‘devotes more resources to the study of climate change than any other branch of the US government’, according to Amitav Ghosh in The Great Derangement. Their conclusions are that, compared to the 214 million people in China whose lives are threatened by permanent drought, the US will not be as badly affected.

Thus goes US military cost-benefit calculus, as mimicked by Thomas Jones: ‘From the point of view of “national security”, [climate change is] the equivalent of having more nuclear bombs.’ According to a Pentagon report, the US has believed since at least 2004 that ‘even in this continuous state of emergency the US is positioned well compared to others’. All this means accepting the constant state of emergency, with its violent and catastrophic consequences, both externally and internally.

The Australian Defence Force, ever goosestepping with the US military, added climate change to its doctrines in 2007. But its border policies have long been a model of securitisation. Along with the rhetoric of ‘threat multipliers’, espoused by Admiral Chris Barrie in a 2016 speech, there is the singularly violent anti-immigration and anti-refugee stance of successive governments.

It is impossible to imagine under our current policy that Australia will welcome climate refugees. On top of that, they also lack legal definition. Jane McAdam, an expert on refugee law, has lamented that there is ‘little political will among governments to create new categories of people requiring protection’.

But securitisation bypasses international law, and relies on the false excuse that climate change itself will increase the likelihood of conflict. Scholars have shown that it is not mass migration that causes conflict, but the militarised response to it. What studies show is that inequality, bad adaption planning and undemocratic governments contribute to a militarised response that exacerbates and ignites tension.

Securitisation is built on the perception of other people as a threat to a static and peaceful way of life. But we know this perception is false, constructed as it is on colonial violence and massive economic inequality. Kalamaoka’aina Niheu testifies to the fight that Indigenous peoples, such as Kanaka Maoli, have mounted against capitalism and climate change since colonialism began ravaging genuinely sustainable ways of life and the lands on which they thrived.

Niheu pays tribute, in her 2019 essay ‘Indigenous Resistance in an Era of Climate Change Crisis’, to the coalitions that have been created with new immigrants – specifically, those brought in as plantation labourers – to counter the destructive environmental policies of the colonial government. One of the lessons from Indigenous resistance, like that at Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota, is the threat can turn inward whenever the military deems it necessary. This has included the Indonesian military protecting BP gas projects in occupied West Papua, or Shell employing extensive private security in Nigeria, as Nnimmo Bassey and Ben Amunwa have shown. Securitisation is applied to internal and external people alike, if the military and its cronies perceive a threat.

What securitisation ensures is that the perceived number of threats multiplies; in doing so, it produces new categories of services that corporations can profit from. The insurance industry is reaping profit from increased risk of natural disasters and extreme weather. Technology firms equip militaries with more powerful means of detecting and preventing cross-border migration, from surveillance equipment and drones to mounted machine guns.

Perhaps most worrying are the mercenary private security corporations waiting to enact violent exclusion from the national to the suburban level. Private security and military companies have already profited immensely from foreign wars, as Antony Loewenstein’s Disaster Capitalism enumerates. Their presence is only increasing, especially in disaster-affected zones abandoned by the military or government. Private security exemplifies the horrifying nexus of securitisation and capitalism whose purpose is to enforce inequalities and sequester scarce resources for the benefit of the rich.

Even fossil-fuel companies profit from the shift from emissions reduction to ‘energy security’, exploiting the government’s insistence on a secure energy grid to exempt themselves from climate action. The same logic is being slowly applied to all essential resources, including food and water. Failing water management and environmental policy in the Murray-Darling Basin led to an (AU)$80 million water buyback by the Government from a Cayman Island-owned corporation conveniently associated with a Coalition minister. Water is now a commodity that can be traded, owned and, therefore, withheld at corporate or state discretion.

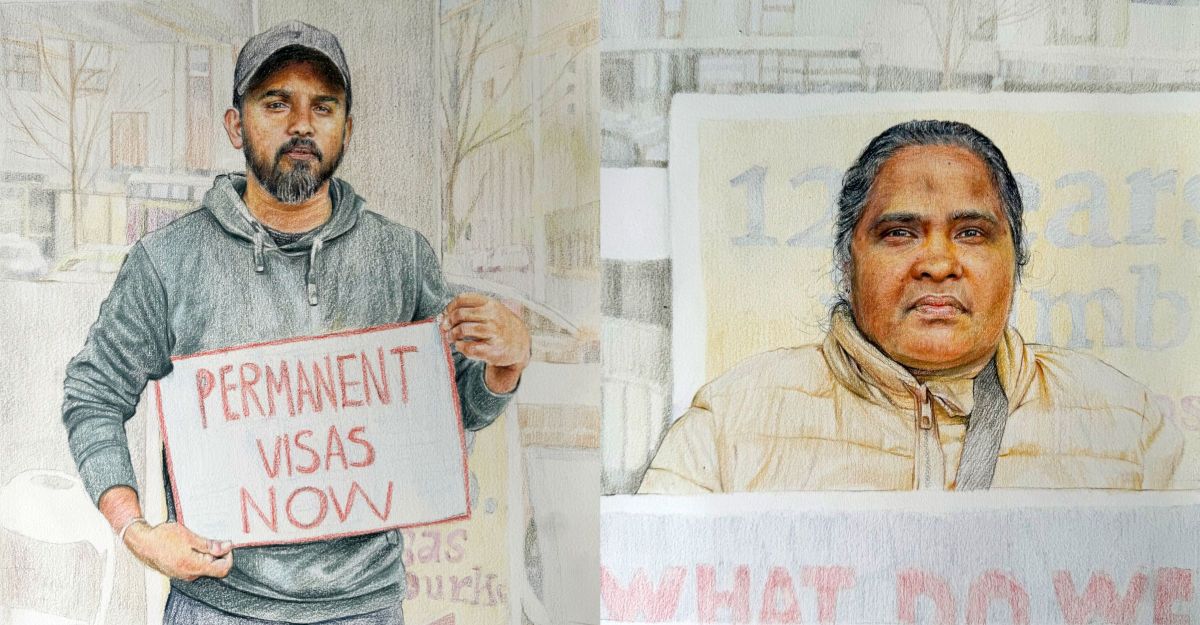

It is not a long way from privatisation to governments and corporations withholding essential resources from non-cooperative populations. The Australian government funds private companies on Nauru – a country where water has historically been scarce – to prevent detainees at detention centres from regularly and freely accessing water. Refugees, who the Australian government claims to have saved from drowning, are now left to dehydrate. Securitisation extends to the violence perpetrated by the unequal distribution of resources under capitalism, as well as the state-sanctioned exclusions that maintain it.

There is a set of perversities that are becoming more evident as neoliberal capitalism consumes the environment. The first is that, along with resources being unequally distributed and the profit from them being captured and controlled by a tiny minority, the suffering from the continued pollution committed by the rich world will be largely borne by the world’s most vulnerable people. Second, the militarisation and closure of human borders takes place to the obscene, ironic benefit of globalised finance. And third, the whole discourse of securitisation is meant to shore up Western countries’ exclusive claim to liberal democracy, to protect their way of life. But it is achieving precisely the opposite, as democratic power is ceded to corporate power and civil rights are ceded to the straitjacket of safety against others.

Pairing what we know about securitisation with the recent calls for a state of emergency to address climate change, rightly targeted by Raven Cretney in Overland’s online magazine, it is easy to see how the crisis will play out. The confluence of militarism and neoliberal globalisation not only exacerbates conflict, but also contributes to the erosion of democratic processes. The so-called state of emergency we are already seeing play out in the Americas provides ample evidence of the disastrous consequences of this approach for democratic and humanitarian responses.

What we need, as always, is more democracy, not militarisation. The environmental movement cannot side with the military if it has any aspiration to global justice. A respondent to Klein’s ‘Let Them Drown’ notes, citing Rebecca Solnit, how communities came together after Hurricane Katrina. But, for many, the lesson of such disasters is that safe communities are defined by violent protection of some against excluded others.

The effects of climate change will be felt across borders; but, for the most part, the poorest, most vulnerable people are most at risk. They have the least resources to adapt to the changed climate, and they tend to live in regions like the subtropics that are most affected. Securitisation strengthens these borders of inequality. To view climate change as a security threat is to accept militarised nationalism and global inequality perpetrated and accentuated by resource expropriation.

If militaries purport to protect us from threats, they have dramatically failed to protect us from the threat our emissions-intensive way of life is to ourselves. It threatens the future of humanity, and specifically and urgently the survival of the people most affected by resource scarcity and forced displacement.

Security is always a restricted, and restrictive, resource. We must insist on de-securitisation. A democratic approach to mitigation means returning resources like water to common control, insisting that they are available to all, and providing opportunities for equal access to them. National borders obstruct this demand, as do the corporate interests that profit from securitised scarcity.

But peaceful resettlement and mitigation also require a great deal of planning and careful consideration. Moreover, it requires a democratic basis that involves citizens of developed countries taking drastic action to cut emissions, fighting against corporate exploitation, and urging governments to demilitarise the response to climate change.

Without these, we are condemned to our sickening gunboat, our imaginations held in thrall to an apocalypse we could have averted, brushing off lifeboats to make ourselves feel safe and secure. And when the lifeboats stop gurgling, we will know the world is lost.

Read the rest of Overland 235

If you enjoyed this piece, buy the issue