Over the last few years, and most particularly in the lead up to this election, it has become clear the fate of the planet rests on the success of our social movements rather than our elected officials. The planet is heating up, the ecosystem is falling apart, the far right is growing, and more and millennials are living worse off than their parents. Things have to shift, and soon.

Yet, many of us feeling this way hoped that the federal election would deliver at least a small victory by bringing Shorten’s Labor government to power on the back of some limited promises around worker’s rights, Indigenous rights and climate change; a victory that could have given us some breathing space and confidence.

But here we are, and the result seems much worse than what we were expecting. Many of us are grieving today. There are jokes about moving to New Zealand, and memes about excising Queensland. More seriously, though, here are some initial thoughts to prompt discussion on what lessons there may be in this moment.

1. This was a win for weird, racist minor parties

Based on current counting, there appears to be a tiny swing against the Liberals (0.7%), and a tiny swing against Labor (0.8%) in the House of Representatives. But the most significant thing is the vote for the minor parties, in particular One Nation and the United Australia Party (UAP). One Nation more than doubled their vote nationally, at 3.0% up from 1.3%. Shockingly, One Nation’s primary vote in Queensland was 8.8%, up by 3.3%. Overall, an array of weird, mostly racist minor parties did very well – and their preferences flowed to the LNP, who has now won the election on the back of preferences from this vote. The Greens, meanwhile, secured 10.3% nationally in the Senate, a reasonable increase on the previous election, but seemingly never to recover to their 13.1% in 2010 when they entered the minority government of Labor’s Julia Gillard.

Bemoaning Queenslanders (or Western Australians, or others) as a bunch of irredeemable racists is not what will take us forward. But we also cannot ignore that One Nation has grown their vote on the back of overt Islamophobia as well as a completely bizarre campaign where they were exposed as willing to take donations from the US National Rifle Association (NRA), and Hanson broke down on television in a way that made One Nation look chaotic and broken. Against all received wisdom about this harming them, in the end it did the opposite of damage. Clive Palmer, meanwhile, has been in parliament before, and barely showed up. For this election, he spent millions of dollars on Trumpian style advertising while refusing to pay the workers from his closed down nickel refinery. Both backed climate denialism. This has both an anti-political quality, where voters are rejecting the two major parties and lashing out, but it also suggests that this quality is hardening into a more overt racist backlash. Which brings me to my second point.

2. It is not racism or economics, but both

The mainstream media is awash with analysis decrying Labor’s supposedly big picture reformism as the problem, arguing voters endorsed Scott Morrison’s apparently safe pair of hands for the economy. Sure, voters did not rush away from Morrison, which might tell us that people don’t really care that much about leadership spills and ‘disunity’ in the way the media often assumes they will. But nor did they rush to stability: as already established, Morrison has been returned on the strength of the vote of minor parties. Arguably, it’s not ‘fear of change’ driving voters but maybe an unarticulated desire for some kind of change that is continually unrealised. Labor’s promise for a moderate level of income redistribution was hardly big target: some things were big spending, perhaps, but it was not a significant vision for social democratic reform to undo decades of neoliberalism. The election was not a vote against social democratic principles nor a victory for neoliberal reform.

The missing link here has been any workers’ action to challenge the economic set up. Left entirely in the parliamentary sphere, the promises to ‘change the rules’ fell flat. And if this strategy doesn’t change, we face the real and present danger of racism continuing to fill the void – and those on Manus and Nauru, those fearful to enter mosques, and the Chinese people being cast as the enemy within will be the ones made to pay. In fighting this, and building solidarity, we can neither discount the appeal of racism nor assume it is hardened and impossible to break.

There’s a danger here that we imagine a default racist white male worker to be the person bringing Morrison to power, but the picture is more complicated. Though the rural seats that voted strongly for the far right are more monocultural electorates, Western Sydney shows that even some in migrant areas were willing to discount, ignore, or buy into the racist discourses of the right this election. Multiple types of voters voted against their own interests in multiple ways.

3. It wasn’t ScoMo’s win, but Labor’s loss

Despite what you may have read in some recent obituaries, Hawke only the last great Labor leader because he killed the possibility of another one. Labor has haemorrhaged members and their primary vote since the early years of the Hawke government, primarily, as Elizabeth Humphrys points out in her book How Labour Built Neoliberalism, because the Accord destroyed the base it relied on to implement the Accord. The Ruddslide of 2007 thus appears as the anomaly that proves the rule: Labor is in (possibly terminal) decline. In this big picture view, it matters less what Labor promised, and more that we’re not willing to believe it anymore.

The other side of this is that Liberal National Party (LNP) is also in crisis. Since the end of Howard, the hard right and the wet liberals have both tried to formulate a winning strategy – either by replicating Howard or aiming for a Rudd-style centrism. Both have failed them, and the internal recriminations that eventually brought Scott Morrison to power ended up leaving him running in the election minus a swathe of famous previous ministers, and with other forms of open disunity, like Jim Molan’s self-promotion, plaguing him.

Considering how ‘easy’ a target Morrison and the LNP seemed, perhaps this just confirms that we were aiming at him with the wrong weapon in the ALP and Shorten. The Greens’ push towards the ‘sensible’ centre, and their emphasis on blue-green electorates, means they have been unable to break through outside of circles of the inner city and tree changers. So that leaves us with an urgent question: what is the left alternative? Without a Jeremy Corbyn or Bernie Sanders figure, it’s not much use dreaming one up. It will need to be collective.

4. The Change the Rules campaign did not work

For over a year, the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) and Secretary Sally McManus have committed all their energy into an electoral strategy based on securing swings to Labor in marginal seats. It simply did not materialise. GetUp, too, spent a year in Peter Dutton’s electorate – and he came back with a swing towards him. Hundreds of committed activists spent hours and hours on this, with great intentions. If nothing else, this was an immense waste of resources and energy.

Labor campaigned against ‘permanent casuals’, but they are a legacy of a trade union movement unwilling to fight for itself. The Australian Centre for Future Work estimated that industrial action has declined ‘97 per cent from the 1970s to the present decade’. Historic low wage growth, the growth in insecure employment (which really expanded in the 1990s, but for various reasons is starting to feel more entrenched): this is the legacy of a movement whose officials seem to have mostly limited their horizons to handing out how to votes.

Instead it has been the school students whose willingness to ‘break the rules’ and march out their school gates that has encapsulated the transformative potential of social action.

5. There’s no easy solution, but there is urgency

If this analysis is true, then it’s not a case of changing Labor leaders or putting more into The Greens, but a question of how we build social movements and a union movement that can fill the political vacuum – and, crucially, challenge racist (and homo/transphobic and sexist) ‘solutions’. Working out how we do that best will be our biggest challenge, and is where our attention needs to turn to now. This column, like others this week, are not the end of the story, but the start of discussion on where we need to go.

Read more perspectives on the 2019 Federal Election

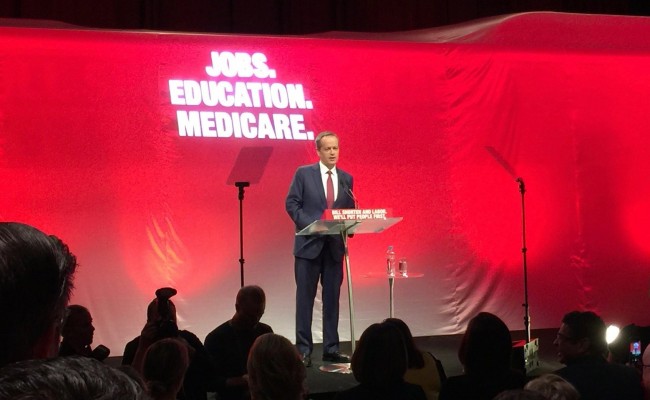

Image: ‘Bill Shorten, Brisbane 2016’ / David McKelvey