In a dimly lit bar, hazy from tequila shots and kitsch neo-rock décor, I light-heartedly expressed to my mates that I loved them. By coincidence, on that same night I ran into a man I had been seeing intimately over the prior months. Tipsy and feeling brave, warm and fuzzy amongst friends, I told him that I loved him too. In the same breath, I also professed my love for cigarettes despite their adverse health consequences, and promptly attempted to avoid igniting my hair while lighting one for us to smoke together.

We shared the cigarette and then he merged back into the bodies amongst the bar while I laid the foundations for what would be the following morning of waking with a splitting headache to the sound of my neighbours having sex.

The days afterwards were characterized by a slow fade-out in contact and prolonged periods of radio silence, a stark contrast to our previously cheerful calls, flirty texts and explicit sexts. The confusion I experienced at first in response to his diminished communication soon gave way to a creeping anxiety that I had done something wrong. I texted more, implying we maintain a dialogue. He agreed to meet me, then stood me up. We rescheduled.

On the night of our rescheduled date, I watched him park his motorcycle beside the bicycle rack before waving at me and disappearing inside to the bar. He returned shortly after with a pint of tomato juice and made small talk about the drink’s healthy and curative properties. He then told me that he felt we should end something that I believed had never actually begun, and expressed his concern that I was trying to ‘girlfriend’ him. I left the conversation wondering if I had been reduced to a warm body with inviting soft parts that had reached an expiry date.

Had my interest in him this whole time actually been perceived as a concealed attempt to ‘put a ring on it’?

As adolescent women, we get called ‘bookish’, or more cruelly ‘frigid’, when we hold interests in things other than our gangly pubescent male counterparts. Or else we become ‘tomboys’, ‘one of the boys’ diminishing our womanhood so that we are treated as equals. We are sexless ‘little sisters’ – intimately invisible, undesirable, unfuckable.

Exploring and acting upon our passions allows us to be labelled as ‘sluts’, a term that men feel can abdicate their responsibility to treat us with depth, empathy and other markers of full humanity. A story of victim blaming is already written for us to step into: we dressed provocatively, we smiled at you, we said ‘yes’ then we said ‘no’, but you knew we actually wanted it.

In adulthood, we merge into the ‘cool girl’, an easy-going female embodiment of male friendship, except with the addition of being effortlessly fit, sexy and capable of giving casual blowjobs. So adept at self-silencing any emotions that might risk upsetting men, we’re just so ‘naturally’ chill. That is until our chameleon act cracks and our supressed emotions flood out. Then we’re ‘crazy’ and ‘irrational’ because we dared to be uncontained.

These narratives construct and position women’s identity in relation to men. They signal in quick shorthand the ‘kind of woman’ we are, what we want and how to treat us. Decades of Hollywood films have reinforced and lucratively capitalized on these familiar tropes. As have decades of pornographic films.

Unlike women, men do not have the same historical and social experience of having identity prescribed to them. Men don’t enter the dating arena foreshadowed by a pervasive cultural assumption that their needs are a simplified binary of ‘single/incomplete’ or ‘coupled/complete’. To be single as a woman, positions you as an outlier on a bell curve of socially ‘acceptable’ feminine identity. The historical social control of reproductive capability and sexual availability are experiences foreign to men.

To be a woman in the dating world is to live in a constant state of resistance to a romantic cultural narrative that has been written for us in the male language.

Irrespective of your gender orientation, to be the recipient of ghosting, fade-out and gaslighting is hurtful. For women, these behaviours are particularly problematic and especially effective. They are modern micro-variations of the historical techniques used to control and disempower us. They are a reminder that when the rules were written, we existed only as problems, property or prizes, not as equal subjects.

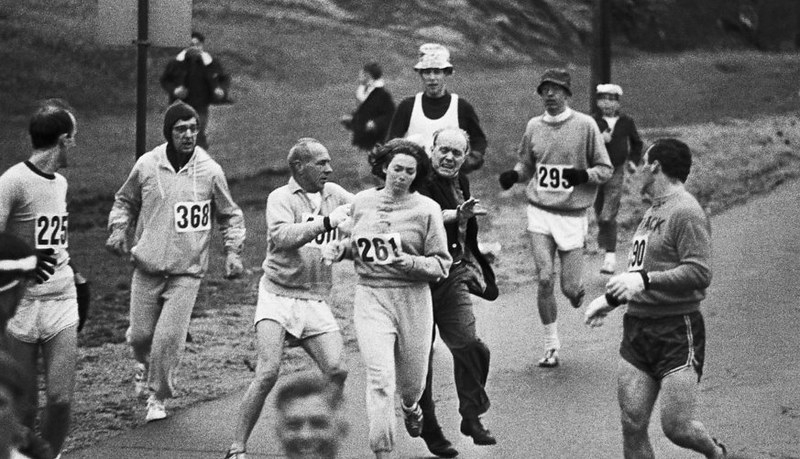

Women’s visibility and power can be kneecapped by actions such as silencing, exclusion, pathologizing of emotional expressions and stereotyping. Dating incarnations of these concepts use the same principles in ways that are triggering and frustratingly familiar. Ghosting employs the power of silence to remind us of our status in relation to men. Being made invisible to them is the repercussion for overstepping our role. The assumption that the underlying motivation of women dating is to ‘lock it down’ reinforces the message, that despite our individual achievements, we are still incomplete without a man’s validation.

The narrative of romance contains deeply embedded social, historical and cultural issues that can compound gender inequality. Without equality we are not afforded the opportunity for individuality. When we hit that sweet spot of ‘equal individuals’, we liberate love and in turn can drop the tired tropes and script our own unique romantic narratives.

A few days after our ‘break up’, I purchased a carton of tomato juice and discovered it to be a refreshing, flavoursome drink. I also discovered that I’d much rather be with somebody because I like them – not because ingrained cultural narratives of romance are so effective at gaslighting me.

Image: ‘Romance’, Flickr