On 28 December I received a WhatsApp group message that made my heart sink. It included a link to an article from the Middle East Eye about an incident that occurred in Battir, in the Palestinian Occupied Territories, just after midnight on Christmas Eve: a time likely chosen in full awareness that many of the Palestinian residents – both Muslim and Christian – would be celebrating.

*

When I had decided I would visit Palestine in October 2018, it was because I wanted to change my feelings about the place. As the daughter of a Palestinian mother who was born in Haifa and lived there until 1948, after the Partition of Palestine and the creation of Israel, any thoughts or news of Palestine had always left me feeling either rage or deep sadness, mixed with a strong sense of impotence.

I wanted to allow myself to feel other emotions that were less polarised. I hoped that going to Palestine would give me more of a sense of the people and the rich culture of that ancient place. Having grown up in England, I spoke no Arabic. Nor had I ever touched Palestinian soil. I wanted to hear people say ‘yalla’ in the way that my mother did, hear the call to prayer, see the streets, churches and mosques, discover how Palestinians experience their daily lives under occupation, taste more of the food – of course! – and maybe even pick an olive or two.

I did all that and more. Organised by Amos Trust, a UK charity, the tour gave me experiences that were amazing, moving and also confronting. I saw the Separation Wall, visited the Banksy hotel and museum, heard stories directly from Palestinians about living under occupation, and experienced their generous hospitality and food. Palestinian food is delicious, plentiful and hugely significant as a means of sharing friendship and sustain family gatherings.

One of the most moving experiences of the trip was meeting Hassan and Vivien, two co-workers who live in Battir. They warmly welcomed us to the village, showed us around the terraces, and gave us a sumptuous meal in the evening before we returned to our hotel in Bethlehem.

Battir is a village of some five thousand Palestinians that lies between Jerusalem and Bethlehem, in the Occupied Territories. Its steep landscape was long ago turned into arable farming and olive-tree planting, using some of the oldest known agricultural practices in the world. These unique characteristics earned Battir a listing by UNESCO as World Heritage Site in 2014. The village was also included in the List of World Heritage in Danger, due to Israeli Defense Ministry plans to build the Separation Wall through the village. As a result, these plans were dropped.

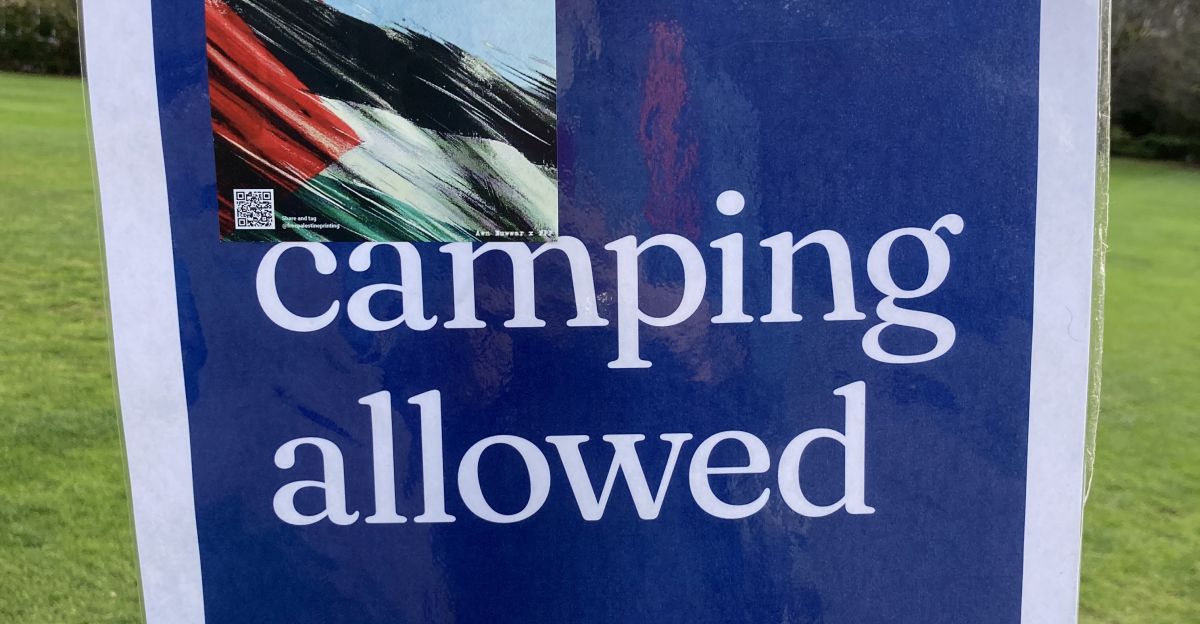

Now, two months after my visit, I was crying into my morning tea as I read how – in the early hours of Christmas Eve – armed Jewish settlers had set up camp on the hills of Battir and started building the structure for a settlement, with the clear intention of displacing the Palestinian villagers and with the support of the Israeli military.

The villagers stood on the surrounding hills and watched in shock, not daring to approach the settlers for fear of being shot at. It was their worst nightmare. They began to phone around, seeking help from both Palestinian and Israeli lawyers, officials, human rights groups and activists. As a result of these efforts, in the afternoon the settlers were made to dismantle their camp and leave the area.

The fear among the villagers is that the settlers will return – indeed, they shouted as much as they left. Like so many residents of the villages in the West Bank, the people of Battir live under Israeli occupation and the constant threat of seeing their homes demolished. Their fear, and mine, is that next time the settlers arrive, Battir may not be protected, despite its World Heritage status, and despite the world voicing – albeit in a quiet voice, certainly not a very loud one – the illegality of the West Bank settlements.

I fear for Hassan and Vivien and all the villagers and farmers who have worked so hard to maintain Battir’s terraces as a community-based enterprise of which they are rightly proud. The events of Christmas Eve also touch that place in me that fears for the survival of Palestine and my mother’s homeland.

Image: World Monuments Fund