‘It all starts with learning how to read, to write, to count and to think in the national language. That doesn’t mean there isn’t an important role for culture in remote schools but nevertheless people need a decent education in the national language.’

So began Tony Abbott’s efforts to use his new role as Special Envoy for Indigenous Australians to advance a narrow, neo-assimilationist vision for remote Aboriginal education. His arguments are not new: they are the latest instalment in pushes for ‘mainstreaming’ that have been gaining steam since the 1990s. Nor are they particularly well made – it is Abbott, after all. They are, however, worth understanding, and critiquing, precisely because mainstreaming policies are already being enacted across remote schools, with disastrous consequences.

Abbott’s arguments are underpinned by a few false assumptions. Firstly, the idea that monitoring school attendance is a solution for improving education. Secondly, the idea that an English-only approach to literacy and numeracy is needed to advance the (supposedly central) task of learning ‘the national language’. And lastly, that the method of Direct Instruction, funded by his government in 2014 via Good to Great Schools Australia, represents a methodological salvo in Aboriginal education. As I will show, these ‘solutions’ are nothing of the sort.

While much has already been said about Abbott’s consolation prize in the leadership spill (NT’s Indigenous Affairs Minister, Ken Vowles, sums it up: ‘It’s about keeping him busy, give him some extra coin, give him a special title’), Abbott’s arguments are a cruder iteration of a bipartisan logic that has been cemented in place since the NT Intervention: the insistence that social issues in remote communities can be explained not by a history of dispossession, racism, and official politics’ rejection of Aboriginal self-determination, but rather by Aboriginal people’s lack of responsibility, and a culture of dependency on government. Uniformly, the solutions proposed have been designed to encourage a market driven assimilation, where communities considered ‘unviable’ should not expect to receive basic services like other communities in Australia. And education, then, needs to be about achievement in ‘viable’ mainstream, market capitalism. As Jackie Huggins said, it’s like the Chief Protector is back.

After launching his crusade with a rather robotic and seemingly rehearsed interview with Warren Mundine on Sky News, Abbott began an embarrassing fly-in-fly-out tour of some remote schools in the Top End. Most awkwardly for him, he was outright rejected by the community in Borroloola. They pointed out that his concern for school attendance was quite misplaced there, as they have some of the highest rates in the region.

But the mantra of ‘getting kids to school’ is a familiar one from Abbott. His government spent $80 million on the Remote School Attendance Strategy (RSAS), which produced no improvement: in fact, attendance slightly declined over the time the RSAS was in place. Regardless, there is little evidence that simply boosting attendance improves educational outcomes. Abbott might crave ‘structure, discipline, repetition’ for Aboriginal students, as he told 2GB, but that seems to reflect a zeal for behaviourist punishment more than any evidence in educational research (because, quite simply, attending school is not the same as getting an education).

Professor John Halsley, who led an independent review into rural and remote education for the Coalition, told the ABC that alongside teacher turnover, the biggest issues effecting schooling in remote communities were outside the school gate rather than inside. Mental health, nutrition, and hearing difficulties all needed attention before singling out schooling. His final report, released earlier this year, pushes strongly for a greater role for Aboriginal knowledges in the curriculum through initiatives like Two-Way science.

In the context of the NT Intervention, school attendance was linked with new policing of Aboriginal lives in remote communities. The School Enrolment and Attendance Through Welfare Reform (SEAM) trial, rolled out in twelve predominantly Aboriginal communities in the NT and Queensland between 2009 and 2017, threatened parents’ welfare payments if their children had ‘unauthorised absences’. As the government’s review notes, ‘no statistically significant effect from the SEAM trial was detected on reducing students’ average rate of unauthorised absences throughout the trial.’ Yet 161 parents in the NT, and 180 parents in Queensland, were cut off their payments – and presumably, their ability to pay for essentials like housing and rent – at some point during the trail.

In that light, Abbott’s promises to monitor attendance should register alarm. It suggests a desire for more of the same control measures that we know, after 11 years of the Intervention, will only make social conditions worse. It is designed to shift blame onto parents, and their kids, for not attending school, rather than talking about either what kind of struggles these families are going through – or, more fundamentally, asking if the schools are offering anything that Aboriginal families think is worth having.

As a review into the RSAS says, a key reason Aboriginal kids and their families disengage from school is that a ‘good education’ does not offer them the opportunities promised. In the Intervention era, real jobs are in short supply in Aboriginal communities. Abbott spells out his answer to this in an instructive video he posted on Twitter, standing alone outside Shepherdson College in Galiwin’ku, that implicitly continues his argument that remote communities are a ‘lifestyle choice’:

the objective [of education here is] … that yes they are culturally competent to live a good life here at Galiwin’ku, but more importantly that if they want to experience all that modern Australian and the modern world has to offer, they can do so. They can make their home if they wish in Darwin, Sydney, Alice Springs in London and New York.

It is not the first time that the community of Galiwin’ku has been urged to focus on English. Shepherdson College began as a mission school but became a government run bilingual school in the 1970s, starting a bilingual Gupapuyŋu program in 1974, and moving to a bilingual Djambarrpuyŋu progam in 1978.

Writing in the History of Bilingual Education in the Northern Territory, former teacher Noela Hall describes the sense of hope and enthusiasm in building schools where Aboriginal language and culture were at the centre:

Despite the immense task of developing learning materials and a literacy program for a language about which most Balanda [European] teachers knew very little, this was a time of vision and possibility … Networking with the other Yolŋu bilingual schools, Milingimbi and Yirrkala, was particularly important as a source of encouragement and support … There were regular bilingual workshops for reporting and sharing progress. In stark contrast to today, we felt supported by the Education Department.

Yet, with bipartisan support, these programs were attacked in 2008 with the ‘First Four Hours’ policy that mandated teaching in English. Thanks to both the full force of the NT Intervention and first hours, instruction in language is now limited to the early years of schooling in Galiwin’ku.

Then and now, government claims that bilingual education was somehow ‘getting in the way’ of learning to ‘think in the national language’ represent a fundamental misrepresentation of bi- and multilingualism. There is an extremely widely accepted understanding that learning literacy, and the ‘schooled’ concepts that go along with it, is logical in the language or languages you speak, and can be built into other languages through this. Most bilingual programs operate through a ‘step model’ that builds literacy through the mother tongue and slowly introduces English as a second language.

But this pedagogical ignorance is only small part of what drives government hostility to bilingual education. After all, the French bilingual schools in Australia are not under any threat. The issue is that bilingual programs in the NT have sometimes represented an opportunity for Aboriginal control of schooling, tied up with a wider desire for self-determination.

That vision of Aboriginal control finds its inverse in Direct Instruction, and Explicit Direct Instruction, that is funded in 19 remote Aboriginal schools. Abbott told Warren Mundine it is producing ‘transformed’ classrooms.

Two schools in Cape York, in Coen and Hope Vale, are run by Noel Pearson’s Cape York Academy and use an Explicit Direct Instruction modelled on an off-the-shelf US program. Teachers deliver partly scripted lessons. It costs around $2 million a year per school.

Direct Instruction was initially developed for children with cognitive dysfunction, so its rollout into Aboriginal schools tells us something about perceptions of Aboriginal children. Many advocates point to the structuring of lessons as useful amid teacher turnover, or suggest the structure helps manage classroom behaviour. But neither of those things is the same as learning how to read, let alone learning to love the world of reading.

In contrast to bilingual programs, which produced reams of resources in their aim to ‘flood communities with literature’ and build a literacy relevant to the community’s interests, the program allows no teacher or school resource development at all. In fact, the Queensland government’s 2016 review found it didn’t even seem to incorporate aspects of the Australian curriculum like history or science in compulsory hours.

That review was prompted after a meltdown at Aurukun school in 2016, which was then part of the Cape York Academy. The principal was the victim of a carjacking and the teachers were evacuated. Aurukun is now trialling a different approach, including bilingual schooling and flexible schooling. Strangely, Abbott did not stop in there on his research tour.

Most literacy instruction in Australia incorporates elements of ‘explicit’ teaching, especially when teaching English as a second language. But this is not the same as subjecting children to rote learning culturally irrelevant texts in an effort to make them ‘think in the national language’. Building literacy should be about extending our sense of self, not about forcing kids to adopt a language and identity that is not their own. The name for that is assimilation.

Yingiya (Mark) Guyala is a graduate of Shepherdson College. He attended when the bilingual program was in full swing, and then attended the (now closed) bilingual Aboriginal college Dhupuma. He now represents the Yolŋu First Nations Assembly in the NT parliament. In September, he told NT parliament what Abbott refuses to hear:

I recently visited schools in communities in my electorate and I was impressed to see they are working through Yolngu knowledge systems, making a space for Yolngu children to journey into a life where there are doors opening towards pathways to both Balanda and Yolngu ways of life. We know what we are doing, we don’t need to be told what to do.

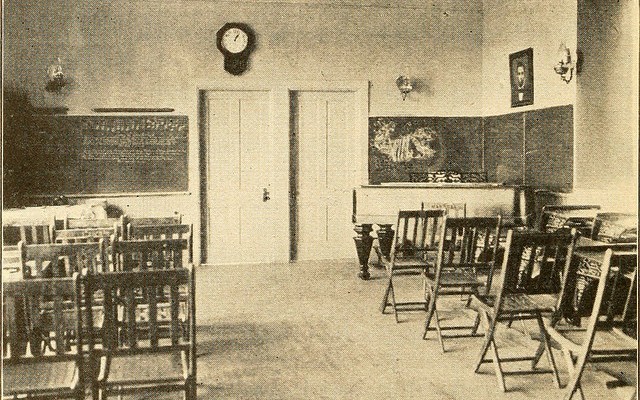

Image: Internet Archive