The campaign against the claimed Chinese Communist influence in Australia has been criticised by China specialists David Brophy, Wanning Sun and others for encouraging ‘stigmatisation of Chinese Australians’. According to Erin Chew, an Australian-born feminist of a Malaysian Chinese family, Chinese students here ‘are feeling the fear and they are feeling targeted’, especially in rural areas. The campaign has also been criticised for its McCarthyism, for instance by former PM Kevin Rudd. David Brophy has described Clive Hamilton’s book Silent Invasion, which I reviewed in Overland earlier this year, as a ‘McCarthyist manifesto’.

Anti-influence campaigners have a quick answer to suggestions that they might be contributing to anti-Chinese racism. As Clive Hamilton points out, there are Chinese Australians who support their campaign, such as the Australian Values Alliance that organised Hamilton’s book launch. Chris Zappone of the Sydney Morning Herald dismisses concerns about racism or anti-China bias as a ‘weaponised narrative’.

The charge of McCarthyism is harder to answer, but not as obviously damaging. McCarthyism, after all, happened on the other side of the Pacific Ocean over half a century ago to alleged agents and supporters of the old Soviet Union. How relevant can that be now? Perhaps critics of the anti-influence campaign need to go into a bit more detail about the historical meaning of McCarthyism. If we do so, we start to see several reasons why it may be too relevant for comfort.

For instance:

– Senator Joseph McCarthy had a lot to say about China and its Communists: the ‘Chinese Reds’, as he called them. The ‘loss of China’ was a major theme of his book America’s Retreat from Victory.

– McCarthy, like anti-influence campaigners today, was inclusive enough to praise Chinese people who were militant anti-communists. He had a very high opinion of Chiang Kai-shek, and he accused the US State Department of betraying Chiang.

– McCarthy, like today’s anti-influence campaigners, was also a strong believer in the power of conspiracies. It was due to conspiracy that the Reds took over China, according to him. Clive Hamilton and his friends are using very similar language about Australia being taken over by conspiratorial means right now.

– McCarthy used the US equivalent of parliamentary privilege to denounce individuals with supposed links to Communist organisations – just as Andrew Hastie, the Chair of the Parliamentary Committee on Security, has recently done in Canberra.

– Senator McCarthy made sensational attacks on some very tall poppies, for instance George Marshall (US Secretary of State 1947–49) and Dean Acheson (Secretary of State 1949–53). In this way, McCarthy could appear as an anti-establishment figure – a populist. Similarly, the current anti-Beijing campaign is targeting tall poppies in the business and political spheres – people like Chau Chak Wing, Huang Xiangmo and Bob Carr – as well as making more general claims about Chinese students and Chinese Australian civic groups.

– The McCarthyist campaign made use of new and existing laws requiring various people to register with the US government. The laws they used were the Foreign Agents Registration Act (1938), which required registration of propagandists for foreign powers, and the McCarran Internal Security Act (1950), which required registration of organisations and individuals considered communist. The Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme Act (put before parliament last year, and passed in early July) establishes a similar registration process, which applies to groups and individuals lobbying or distributing information for a foreign government or party.

– A US national security body, the FBI, played a big role in the pursuit of supposed foreign agents in the McCarthy period. So much so, that historian Ellen Schrecker has suggested the term ‘Hooverism’ (after the FBI chief J Edgar Hoover) as an alternative to ‘McCarthyism’. Today, Australia’s national security body, ASIO, is briefing news media about its ‘top secret’ work, and its director Duncan Lewis has asked parliament to approve the proposed new laws.

Joseph McCarthy (Artist: Ernest Hamlin Baker; National Portrait Gallery)

The McCarthyist period, also remembered as the Second Red Scare, was a response to real geopolitical changes. The victory of the Communist Party in the Chinese Civil War was a recent fact then, just as China’s emergence as an economic superpower is a fact today. Perhaps it shouldn’t be a surprise if a comparable culture of fear – a new Red Scare – is taking shape here and now.

What, if anything, does McCarthyism have to do with racism? Consider what happened to the Council on African Affairs, founded in 1937 with a slightly different name, and renamed in 1941. The CAA was a volunteer organisation which published a journal called New Africa. It campaigned against colonialism and apartheid, and publicised the activities of the South African ANC, the party of Nelson Mandela.

Leaders of the CAA included several prominent members of the African American community, including the world-famous singer Paul Robeson, and the sociologist and author WEB Du Bois. Both Robeson and Du Bois took a positive view of the Soviet Union, which had opposed imperialism in Africa since the days of Lenin.

Council on African Affairs Protest, New York City, 1952 (Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library)

In 1948, a co-founder of the CAA, Max Yergan, broke with the group, complaining that it had been infiltrated by Communists. According to the African American history site Black Past, his dramatic change of position was ‘certainly related to the pressures exerted by constant government surveillance and threats of prosecution’.

In 1950, Paul Robeson’s passport was cancelled, and he was denied the right to travel outside the USA. In 1951, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) declared the CAA ‘subversive’. In 1953, following an FBI investigation, the US Attorney General, Herbert Brownell, ordered that the CAA register under the McCarran Act as a communist organisation. The CAA publicly objected to registration, but by 1955 its leaders felt they had no choice but to disband.

Those who denounced the Council on African Affairs were not all stereotypical white racists. Max Yergan was black, and had been a pro-Soviet leftist. Herbert Brownell was a comparatively liberal white Republican who worked to end segregation in the southern states of the US. Nonetheless, the political result of the anti-CAA campaign was to help the US government keep onside with racist regimes in southern Africa, a policy that continued until the end of the Cold War.

Was it sinister or natural for African Americans in the 1950s to take an interest in events in Africa, such as the ANC’s anti-apartheid campaign? Is it sinister or natural for Chinese Australians today to take an interest in events in China, such as the country’s fast modernisation?

Perhaps there are subtler forms of racism than segregation and White Australia?

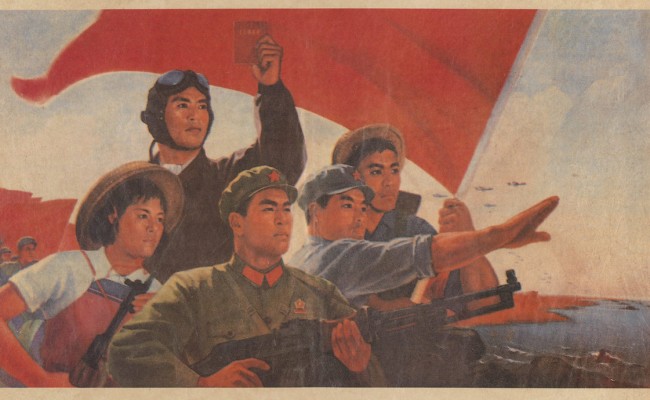

Lead image: 1960s propaganda poster