As a New Zealander, I have always been puzzled by the immense hold that journalist, poet and short-story writer Henry Lawson (1867–1922) has on the Australian imagination. Some of his writing is undeniably powerful, and his politics (anti-rural militant socialism alongside xenophobic nationalism) intriguing, yet his reification seems disproportionate. The more I read about his life, the more unappealing his character becomes. ‘The evidence for the claim that he was a great writer is easily accessible and incontrovertible,’ Brian Matthews observes. ‘That he was a great human being is another matter.’

Lawson wrote his ‘Fragment of Autobiography’ between 1903 and 1908, when he was in the throes of advanced alcoholism. In this unreliable memoir, he represents his childhood and formative years as uniformly miserable, from the perspective of his destitute present. At fourteen, following an illness, he developed severe deafness and became increasingly isolated, both from his family and the social world more broadly.

Lawson’s personal tragedies are still compelling, some 150 years after his birth. His friend Tom Mutch observed: ‘Everything he wrote he lived’. Though not strictly accurate, Lawson’s writing conveys a sense of authenticity that resonates with his readers.

In Leaving Home with Henry (2010), Phillip Edmonds imagines Lawson escaping from the National Archives in Canberra where he has been ‘trussed up as a national icon’, the ‘caretaker of everyone else’s Australian dream’. He is driven all around contemporary Australia by a researcher named Trevor, assiduously avoiding his old haunts. Trevor and Henry part ways after a gruelling road trip, punctuated by Henry’s disagreeable whining. Henry heads off alone to Sydney, where he finds a bronze statue of himself in the Domain. ‘[T]here he was,’ Edmonds imagines Lawson, ‘looking wistful and quite rural to the unreconstructed eye and for a conceited moment, he was pleased, wondering whether he really looked like that.’

If Lawson returned to Australia in the twenty-first century, he would be amazed by the number of commemorations in his honour, including at least seventeen monuments and two competing festivals. Although Lawson expressed a dislike for ‘the bush’ on a number of occasions, his reputation remains strongest in rural areas, and the Grenfell and Gulgong festivals – both held annually around his birthday, 17 June – are perhaps the most striking manifestations of Lawson’s posthumous influence.

Before leaving Melbourne to attend them, I read Joe Wilson and His Mates (1900–01), a collection of short stories set in the country of Lawson’s youth. They are incredibly bleak, full of sadness and conflict, with only fleeting moments of connection between people. The stories follow the disintegrating marriage of Joe and Mary as they face the many brutal hardships of bush life. ‘Water them Geraniums’ describes Gulgong as a ‘wretched remnant of a town on an abandoned goldfield.’ The Wilsons’ neighbour, Mrs Spicer, raises a brood of children alone on a poor selection and tries desperately to grow geraniums outside her shack. At the end, Mrs Spicer is ‘past carin’, willing herself to die after her son brings disgrace on the family. In ‘Brighten’s Sister-in-Law’, Gulgong is said to be ‘dreary and dismal enough’. Joe and Mary struggle to keep their ailing son Jim alive in the bush, with no medical care. The child’s convulsions are a terrifying sight:

Jim was bent back like a bow, stiff as a bullock-yoke, in his mother’s arms, and his eyeballs were turned up and fixed – a thing I saw twice afterwards, and don’t want ever to see again.

Written while Lawson was in London seeking his literary fortune, the Joe Wilson stories catalogue the miseries of life in remote New South Wales. I think Lawson’s concern for bush people, especially the women and children living in wretched conditions, reveals his compassionate side.

The next morning, after an indifferent sleep in a hard bed in a Cowra motel, I drive to Grenfell, thirty minutes away. Named after gold commissioner John Granville Grenfell, the town began as a mining settlement. Lawson claimed that he was born during a storm in a tent on the diggings on 17 June 1867. Colin Roderick dismisses this story as a concoction, and places the moment of birth on a more temperate evening in a far less romantic building in what was by then a fairly well-equipped township. Either way, it must have been a rude shock for Lawson’s nineteen-year-old mother, Louisa, to deliver her first baby in such basic circumstances. Lawson claimed that it was not easy for Louisa to handle him as a baby because he had regular uncontrollable screaming fits.

Lawson’s family only lived in Grenfell for six months before making the trek back to New Pipeclay – later named Eurunderee, meaning ‘one tree’ in Wiradjuri – but his birth has huge significance for the town: a sign on the edge of town proclaims it the ‘Birthplace of Henry Lawson’.

With its tall, double-fronted facades and wide main street, Grenfell has a Wild West quality. At the height of the Lawson festival, country music artists line up here, competing for the change of passers-by. There are weathered faces below cowboy hats, mothers with babies in pushchairs and elderly people with walkers and wheelchairs and heavily tattooed men cluster in low-slung jeans and caps with sunglasses perched on the peak.

A steady stream of people take selfies with a bronze effigy of Lawson sitting on a park bench with pen in hand. This ‘interactive’ seat is the latest addition to a range of commemorations, including a bust on a plinth, the Loaded Dog café and several murals. Further down the street, a gigantic papier-mâché Lawson head has been plonked incongruously in the middle of a roundabout.

The festival parade consists of vintage cars of all kinds and some half-hearted attempts at dressing up, but no Lawson impersonators or period costumes. The local school children march past dressed up as Lego figurines in contrast with the monster procession of the first ‘Back to Grenfell Week’ of 1924, which featured children in elaborate nineteenth-century outfits. Parades can tell you a lot about what a place values – here it is cars and children.

At Lawson Park the following morning, I eat hot damper smothered in golden syrup served by volunteers at a breakfast marquee, while Lawson’s works are recited by devotees in what appears to be bush uniform: moleskin pants, Blundstone boots and akubra hats. ‘Said Grenfell to My Spirit’ (1911) is a perennial favourite.

Said Grenfell to my spirit, ‘You’ve been writing very free

Of the charms of other places, and you don’t remember me.

You have claimed another native place and think it’s Nature’s law,

Since you never paid a visit to a town you never saw:

So you sing of Mudgee Mountains, willowed stream and grassy flat:

But I put a charm upon you – and you won’t get over that.’

The spot where Lawson was supposedly born, once slap-bang in the middle of the Grenfell gold diggings, is now marked by a white obelisk. In 1924, Henry’s wife and daughter – both named Bertha – attended the unveiling ceremony and planted a gum tree. The Grenfell Town and District Band played ‘Home, Sweet Home’, echoing Henry’s own words:

You were born on the Grenfell goldfield,

And you won’t get over that.

Weaving through the large crowd of onlookers, I discover a Lawson barbeque complete with memorial plaque. This confirms my impression that almost everything in the town, from a lowly barbeque to the high school, is named after him.

I buy a watery coffee from an American-style diner, fill up with petrol and drive north to Gulgong for the Henry Lawson Heritage Festival. Located in the Central Tablelands, about 300 km north-west of Sydney, Gulgong is seemingly frozen in time. As I drive into Mayne Street, I notice gold-rush-era buildings that seem untouched, almost as if the twentieth century never happened.

The Lawson family – at the time consisting of parents Peter and Louisa and their two children, Henry and his younger brother Charles – moved from Grenfell to Gulgong in 1870, following a long stream of gold diggers. Henry remembers the chaotic journey: ‘in a cart with bedding and a goat and a cat in a basket and fowls in a box’ accompanied by ‘teams with loads of bark and rafters, and tables upside down with bedding and things between the legs, and buckets and pots hanging round, and gold cradles, gold dishes, windlass boles and picks and shovels; and … drays and carts and children and women and goats … and men on horses and men walking.’

At the outset, Peter prospered and was able to send Louisa and the boys to Sydney for a holiday. They came back to Gulgong for another year, which was crowded with memories for Henry – visits to diggers shafts, ‘the rattle of the cradle, the clack of the windlass, walks about the bustling little town, with its shops, the circus, and a garish theatre’.

I miss the Gulgong festival parade – all that can be seen in Mayne Street are a few stallholders and a fortune teller’s caravan. I stop a local woman outside the supermarket and ask her opinion on the festivities. She tells me that the parade was led by a convoy of vehicles that had travelled from Grenfell. It is an annual pilgrimage that switches direction each year, connecting the two Lawson festivals, which otherwise seem to be in competition with one another.

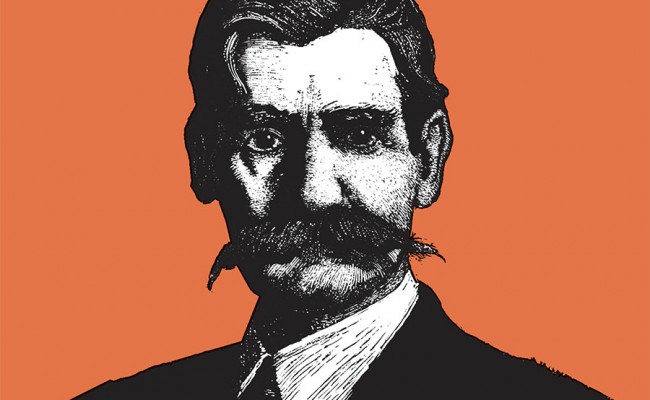

A Lawson impersonator is greeting passers-by in full costume: walking stick, overcoat, hat and bushy moustache. I introduce myself, and slipping out of character for a moment, the impersonator tells me his name is James Howard and that he is an amateur actor who has been impersonating Henry in Gulgong for a number of years. The locals appreciate having Henry there ‘in person’ to welcome festival-goers. James says he is naturally a very shy person and that it is challenging to talk to strangers. After a weekend of being Lawson in Gulgong, all the while harbouring a very bad cold, he is keen to change his clothes and go back to being himself.

I decide to take a guided tour advertised in the festival brochure. On the way to the Henry Lawson Centre, I notice that many of the shop windows feature black-and-white stills by nineteenth-century photographers Henry Beaufoy Merlin and Charles Bayliss, of the American and Australasian Photographic Company, who had travelled to the town of Hill End in 1872 to record the gold rush. Their patron was the newly rich Bernhardt Otto Holtermann, who employed them to photograph gold-producing areas in New South Wales for exhibition overseas. Their photographs, known as the Holtermann collection, were rediscovered in a Sydney garden shed in 1951, enabling Gulgong to capitalise on its Lawson association. The town is proud of the fact that Lawson and images of Gulgong from the Holtermann collection appeared on the $10 note in 1966. Even though Henry was replaced by his rival AB ‘Banjo’ Paterson in 1993, the Lawson $10 note is still featured on a range of souvenirs.

The Henry Lawson Centre is located in a hall that once belonged to the Salvation Army; it retains the air of a church, with the original ‘JESUS LIVES’ altar still in place. Affixed to the back wall are the Eureka and Norwegian flags, the latter referring to Peter Lawson’s country of birth. There are Lawson relics (or copies of them) everywhere. My eye is drawn to the ‘Death-mask hand’, a 1925 copy of the original casts made at Lawson’s deathbed in 1922. A replica of a flour bin made by Peter reminds me of Lawson’s poem of the same name:

By Lawson’s Hill, near Mudgee,

On old Eurunderee –

The place they called ‘New Pipeclay’,

Where the diggers used to be –

On a dreary old selection,

When times were dry and thin,

In a slab-and-shingle kitchen

There stood a flour bin

I rummage through an old suitcase full of clothing and laminated copies of handwritten letters and other writings, as if Henry had just left it behind on his ramblings around the country. In the back room, my eye is caught by a section of ancient wallpaper in a picture frame. A handwritten note in the top-right corner says ‘Wall paper from Henry’s Eurunderee home (now demolished)’ with a blurry old photo of the original house added below.

The variety of Lawson items for sale is impressive: wooden glasses cases printed with his portrait, postcards, pens, tea towels, key rings and locally compiled anthologies of poems and stories. As I buy bookmarks and postcards, the woman behind the counter tells me she doesn’t usually work there, but the other elderly volunteers are too exhausted by festival organising.

With a handful of other tourists, I wait outside the centre for the tour guide, but no-one shows up. In the meantime, a poetry event has begun inside. Through the doors I hear a woman passionately reciting bush poetry about domestic violence. An elderly volunteer steps outside to tell us that the usual guide has recently died and she is trying to find a replacement. Eventually a man attending the poetry reading takes us around town, despite his ‘pinned wing’ (an injury sustained in a recent fall over one of the town’s steep quartz-stone gutters).

Our tour includes all the local sights: the Opera House (Lawson’s ‘garish theatre’), the Red Hill mineshaft where gold was first discovered, the Ten Dollar Town Motel, which houses Phoebe’s restaurant, named after Lawson’s maternal aunt, Phoebe Albury, who ran a drinking establishment there. The Lawson children stayed with Phoebe often, particularly when their father was working as a carpenter in remote locations. Henry would play with Phoebe’s parrot and watch her operate a newfangled sewing machine.

Later, I come across a haunting photograph of Louisa, Phoebe and baby Charles standing outside Phoebe’s dressmaking shop. Their immaculate dress contrasts strikingly with the rough-hewn building behind them. Louisa looks down at Charles, who is wearing a dress and pinafore, with his back to the camera. Phoebe, starring into the middle distance, appears slightly blurred, as if she had moved while the photograph was being processed. Three-year-old Henry is nowhere to be seen.

Grenfell and Gulgong have firmly claimed Lawson, yet it was in Eurunderee where he lived, on and off, from the age of six months to fifteen years, and so it’s to Eurunderee that I head.

I overlook the KEEP OUT sign on the gate, climb the hill and peek in the windows. Lawson’s poem ‘The Old Bark School’ (1897) described it as a ramshackle building made of ‘bark and poles, the floor full of holes’:

Where each leak in rainy weather made a pool;

And the walls were mostly cracks lined with calico and sacks –

There was little need for windows in the school.

The Eurunderee Provisional School has had three incarnations – the first, opened in 1876, was an old bark building built by parents; the second was built by Peter Lawson in 1879, at which point the bark hut became the schoolmaster’s residence; in 1930, the building was demolished and replaced by a building transported from nearby Canadian Lead, another town once famous for its gold. The schoolhouse now standing in Eurunderee is symbolically powerful rather than entirely authentic, having been extensively renovated for educational purposes.

Henry’s mother lobbied tirelessly for the establishment of a school at Eurunderee because the way to the existing school was littered with old mineshafts. A nine-year-old boy named Tom Aspinall had died after falling down one on the Lawson’s land before Henry was born, making it a pressing concern for Louisa.

Incredibly – given his later literary achievements – Lawson’s formal schooling lasted only three years. Opinion is divided over why he left school. Local legend has it that John Tierney, the schoolmaster, accused Louisa of plagiarising Byron in one of her literary pieces, leading to a ‘falling-out’.

A key place in ‘Lawson Country’ is the site of the family’s old homestead in Eurunderee, not far from the school. Built by Peter, the house was a modest two-roomed dwelling made of timber with a corrugated-iron roof. It served as the model for many of the homes in Lawson’s stories – the home of the drover’s wife, the old digger’s home and the settler’s hut beside the road where the teams went by in a cloud of dust.

When the Lawsons moved to Eurunderee, Peter toiled to fill in the abandoned mine shafts; the property was littered with mounds of mullock, a pudding-like mixture of quartz and glutinous clay, known as black vite-wash or pipeclay. Occasionally he would sink a shaft of his own. Brian Matthews describes Peter as an addict, ‘enslaved by the chance of gold’, even after the rushes were over. Louisa, now mother to five children, worked hard to survive as a farmer and postmistress.

When the family returned to Eurunderee in 1873, Henry was disappointed that the tree he remembered from infancy was gone. The tree had ‘haunted’ his early childhood because he feared it would fall on the tent they lived in before the house was built. The tent and the tree were his earliest memories – they stood there ‘back at the beginning of the World’ and it was a long time before he could conceive of either having been removed. They were conjured up in his ‘Fragment of Autobiography’ years later: ‘But the tent and the tree still stand, in a sort of strange, unearthly half light – sadder than any twilight I know of – ever so far away back there at the other end of the past.’

In his middle age, Lawson’s thoughts turned more and more towards the area around the Eurunderee goldfields. In 1914, with his friend Tom Mutch, Lawson revisited the old diggings, identifying the places featured in his poems and stories and reminiscing about the people who had gone before.

In 1946, twenty-four years after Lawson’s death, George Farwell visited the ruins of the Lawson homestead. He described it as ‘a shabby, tin-roofed slab affair’ that stood in a small garden, bare of anything but thistles. Farwell picked the lock of the front door to enter. Daylight filtered through the cracks in the rotting slabs. A few dark shreds of wallpaper hung from the wall beside the fireplace. Hessian strips festooned the ceiling. White ants had played havoc with the stringybark slabs, and sheep droppings were everywhere.

The house was demolished the same year, despite energetic campaigns by left-wing intellectuals, the Fellowship of Australian Writers and various Lawson societies. In 1949, the Cudgegong Shire Council and the Housing Commission of New South Wales produced what they described as a ‘simple and dignified’ memorial opened by Lawson’s widow, to great fanfare.

On my way to the Eurunderee homestead site, my phone loses internet access, rendering Google Maps useless. Cursing my phone company and my inability to navigate without technology, I drive around and around, unable to find the right road and feeling increasingly anxious. After forty minutes or so, I reluctantly give up and drive in the direction of Canberra airport.

When I arrive home, I obsessively google images of the homestead, but it’s hard to make out the remains. A photo of the post-demolition ruin shows a blackened chimney standing out against the sky, the only tangible connection to Henry’s household. The 1949 memorial was designed to bring the remaining elements together – with the addition of a wall, a covered archway, a picnic table and a rubbish bin – but it’s the original ruins that resonate most strongly with me.

As Robert Dessaix observes in Twilight of Love: Travels with Turgenev, an account of his visits to places once haunted by the Russian author Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev: ‘It’s odd: the more perfect the stage set, the less my imagination feels inclined to wander.’ Because I failed to see the newer memorial with my own eyes, I’m more able to visualise the house as it was in Lawson’s time. I imagine all the hot dinners and billies of tea prepared over the fire by his long-suffering mother. I imagine a dismal, cramped interior crowded with people, as well as the room where he slept with his four siblings and the yard marred with mine shafts.

These tiny domestic details enable me to see Lawson as a real person who lived and suffered, prompting a grudging admiration for the distance he travelled from his birth in a tent on the goldfields to literary celebrity in Sydney. If nothing else, this literary pilgrimage has made Lawson more relatable, bringing him back down to human size.

Read the rest of Overland 230

If you enjoyed this essay, buy the issue