Around this time last year there was an air of political fatalism. More of us than ever could diagnose the ills of capitalism – growing economic inequality and its degradation of human dignity – but the mechanisms that create and sustain this organised greed seemed to be irreversible. The far right was pinning blame on the racialised immigrant figure, whether the problem was job insecurity or national security. And their remedy offered was a return to a conservative, white-nationalist past. Between Donald Trump’s election victory and the Brexit result, far-right xenophobia was making a new sweep across the west. Not until the UK election this year was the left able to see a clear shift away from this bleak political situation.

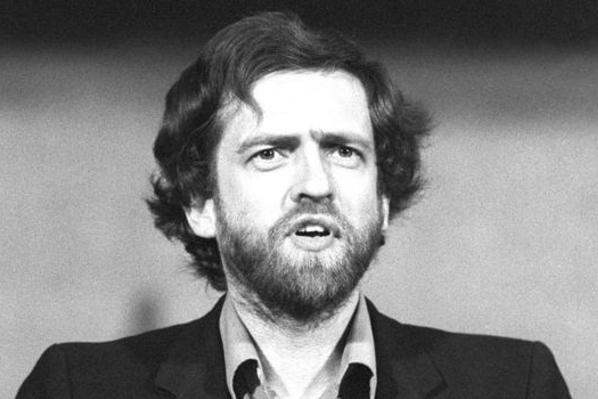

The UK election result gave a renewed hope to the left’s ability to create a fairer society. Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn ran a positive campaign that addressed the problems created by global capitalism. It didn’t use immigrants as scapegoats but called for the collective building of a UK that was ‘for the many, not the few.’ This campaign changed the political discourse. It put socialist values and policies up as viable politics for the first time in many years. As Corbyn summed up, ‘our positive campaign has changed politics for the better.’ And the reason for its success? ‘People voted for hope.’

Against the bleak politics of 2016, Corbyn offered hope. Of course many other politicians offer hope, or at least attempt to; it is a driving force in politics. But what differentiated Corbyn from Trump, and from liberal leaders like Justin Trudeau and Emmanuel Macron, is that the core of his political hope is faith in the people. His hope is a democratic one. Because it is the ‘people and not the voting booths, not the flashing campaign slogans, not the event-driven parliamentarians that are the subjects of democracy.’

We find that what is important is not only hope in politics, but the type of hope in politics: hope that is ultimately about having faith in the rule of people.

Politics is concerned with both answering and realising questions: how do we want society to be organised? Upon what values and principles should society be founded? For politics to become more than words, there needs to be a belief in the possibility of actually creating a better world. Without hope we are disillusioned, disempowered, apathetic. Seeing the problems that exist in the world, and having a critical eye, is not a danger to the pre-existing system. Only when one believes that things could be different, and that we have a role in creating this change, do politics begin.

As Paulo Freire puts it:

The idea that hope alone will transform the world and action undertaken in that kind of naïveté, is an excellent route to hopelessness, pessimism, and fatalism. But the attempt to do without hope in the struggle to improve the world as if that struggle could be reduced to calculated acts alone, or a purely scientific approach, is a frivolous illusion.

The Trump election campaign incited a lot of fear, namely of foreigners, however it was also an optimistic campaign. He promised to ‘bring back’ a version of an American past that appealed to many – to ‘Make America Great Again.’ Hillary Clinton, in contrast, focused on her criticism of Trump and painted a doomsday scenario that would result from his presidency, emphasising his inexperience and instability. A vote for Hillary was a vote against Trump. But ultimately Clinton’s lack of an alternative vision to address increasing inequality or resentment towards the establishment lead to her defeat.

French President Macron, whilst politically similar to Clinton (both centrist liberals), differed in his message. His 2016 campaign ‘En Marche’ (‘Go Forward’) promised of a France full of opportunities; a France returning to its former glories, in a modernised form. Macron attacked his main rival, far-right candidate Marine Le Pen, as a ‘a high priestess of fear’ for utilising anxiety created by terrorism, for demonising Muslims and for justifying curbing immigration. As Murray and Soyez put it, this was a campaign of opportunity versus a campaign of fear.

VICE argued that Corbyn allowed previously disengaged and disillusioned citizens, particularly youths, to challenge the bleakness of the projected future, and to be a part of something that could build a better and fairer UK. ‘What we’ve all learned from the election last night is that how things are is not the same as how they will always be. People can overturn every certainty imposed on us. The world is ours to change,’ Corbyn declared. The Guardian argued that Corbyn showed that people are willing to embrace radical politics, and the politics of hope. For Jacobin, Corbyn’s campaign was the ‘rebirth of hope’ because it revitalised class politics in the UK. And NME, another youth-based media outlet, described Corbyn as a ‘messianic figure of hope to his followers’.

Democratic hope places its faith in the people. As Arson frames it, it is a social hope. It is not about what a charismatic leader, an economist or religious figure can do, but about what we can do. Not the belief in an external other, but a hope in our own collective ability to take responsibility for our situation and fashion it through organised action.

In an interview with the New Yorker, when asked what Britain would look like under his leadership, Corbyn responded:

Well, it is not going to be under Jeremy Corbyn … I am hoping there will be a Labour Government, of which I will be obviously a big part. But it’s about empowering people. That is what democracy is about. Is it going to be complicated? Sure. Is it going to be difficult? Absolutely. Are we going to achieve things? Oh, yes.

Corbyn is not the first leader to profess the importance of democracy. Every politician I have mentioned advocates ‘democratic values,’ especially, as Rancière poignantly notes, when it justifies foreign intervention. However, the actual politics and policies that they endorse defy the real core of democracy: the rule of the people. Trump used a lot of anti-establishment rhetoric but his campaign was not about empowering people to have faith in their collective abilities, but about trusting him to fix problems on the basis of his business credentials.

Similarly, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Macron are presented as charismatic leaders who are ‘fixers,’ whereas Corbyn’s, and US Senator Bernie Sanders’, politics are that people should have faith in themselves and their ability to create change. Arson argues that both Sanders and Trump offer hope to the working-class American. They make similar diagnoses of the ills of the country: job insecurity and loss. However, the hope Sanders offers is based on what we can do about it.

Much of Corbyn’s success has been attributed to the Labour Party’s 2017 Manifesto. In its preface, the first thing it establishes is faith in the British people’s abilities. In regards to Corbyn’s campaign tour, he writes:

For me, it’s been a reminder that our country is a place of dynamic, generous and creative people with massive potential … So let’s build a fairer Britain where no one is held back. A country where everybody is able to get on in life, to have security at work and at home, to be decently paid for the work they do, and to live their lives with the dignity they deserve.

The vision painted is followed through with a set of policies aimed at extending local participatory powers. The Conservative Party’s manifesto, on the other hand, has no section regarding ‘extending democracy.’ It tells the citizens of the UK they need strong leadership to guide them: ‘Now more than ever, Britain needs strong and stable leadership to make the most of the opportunities Brexit brings for hardworking families.’ British Prime Minister Theresa May, as with Trump and Macron, asks the people to place their hope in their leaders.

Corbyn’s faith in the people is not a blind optimism, as his electoral result shows. When May announced the UK election date, she was still amidst a honeymoon phase and held a huge lead against the Labour Party, and wanted to extend her majority. It appeared a clever tactical move that could potentially crush Labour. But what we saw was the opposite – from the huge surge in Labour Party membership and the increase in the number of Labour seats held (the greatest number won by Labour since Tony Blair’s 2001 victory, which forced the Tories into hung parliament), to what was probably the most important outcome – the reframing of the debate away from xenophobia, to how a more egalitarian and fairer UK could be created.

Corbyn revived the party on traditional socialist labour values in a testing time. During the campaign, many from the left were sceptical, and many outright opposed him. This opposition was rarely targeted at his politics (why would they be against policies for a better public health system and tackling inequality?). Rather, they argued that Corbyn could never gain mass appeal. He was ‘too left’ for the mainstream. But this rejection of Corbyn’s leadership was ultimately a rejection of the people’s right to govern and of the belief in the core of democracy.

After the shock Brexit result, one half of the nation celebrated it as ‘Independence Day’ while the other described it as a failure in politics. Liberals were quick to speak of the dangers of excessive democracy, inciting a general distrust in the popular vote; they argued people voted to leave because of the failure to understand the economic and political implications (as well for xenophobic reasons), and that the referendum should have never been allowed to happen. The underlying view is that experts, not the public, should decide serious political matters, and moreover, that politicians’ duty lies not in facilitating the exercise of democratic decision-making, but to contain and repress it. Rancière sums up this contradictory view of democracy: ‘The thesis of the new hatred of democracy can be succinctly put: there is only one good democracy, the one that represses the catastrophe of democratic civilization.’

Corbyn made the bold move, bold because it is so foreign to politicians, to put his faith in people to embrace, and to collectively govern on, socialist values. The importance of the youth vote in the UK election illustrated that Corbyn’s faith in people fostered democratic participation. The election had more than two million new voter registrations, many of whom were young voters. Labour similarly had a surge in new membership driven by the young. The campaign empowered youth by giving them the opportunity to not just be victims of the consequences of capitalism, instead encouraging them to be agents of change. Many had dismissed the youth as apathetic because they were a demographic with a traditionally low voting turnout – in the previous election only half were registered – but Corbyn engaged them, created dialogue, gave the hope that the world could be better, and that they had a crucial role in that change. In the NME interview with Corbyn, Mike Williams writes:

The election wasn’t about Brexit any more but the kind of country we want to live in, the kind of values we want to hold, the way we want to treat our old people and the future we want to create for our youth.

This article is centred on one figure, however it should not be mistaken as a call to merely follow him, and rely on him to fix and solve societal ills, as liberal centrists who adore Macron or Trudeau do. Corbyn has many admirable characteristics and political views, however, he is not the agent of democracy. Democracy begins when people have faith in their capacity and right to rule, and create mechanisms for this to happen. We have spent so long believing in an individualist doctrine that is fundamental to capitalism that we have taken on aspects of our society as given: that people will always fear foreigners, and will put forth their own interests at the expense of the collective good. Ultimately there is hope, that people do not want to live in a dog-eat-dog time where we fear our neighbours, and that we are willing to ask, and answer, the questions of how to create a better world. One of our most powerful tools in this moment is democratic hope.