When I first encountered ‘Vindaloo against Violence’ in the aftermath of the Indian student attack fiasco in Melbourne in 2009–2010, I didn’t know what to make of it. Beef vindaloo is a dish I never encountered in my childhood in northern India, but saw plastered on Indian restaurant menus everywhere in Australia. The circuits of colonial cuisine aside, I didn’t understand why food was the best way to express solidarity with brown people from the subcontinent who may have been facing undue racism at a particular moment in Australia’s history when the laws of skilled migration clashed with the forces of economic and social disenchantment.

Seven years or so later, this ambivalence is softened when I am no longer a member of the community most in need of a gesture of solidarity. As Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers has worsened (with those in offshore detention centres facing abuse, and those in the community stuck in limbo or without work), I have wondered about why we need to see the refugee as either victimised or resilient to offer help. And can such resilience remain static, in the face of ever-shifting and harshening policies towards refugees?

In a bid to meet refugees and to advocate for them (especially to my students), I have found myself wandering into ‘family dinners’ cooked by former asylum seekers at Parliament on King (a Sydney café), accompanying friends to Middle Eastern feasts organised by ‘House of Welcome’ (an organisation in western Sydney that provides various services to new refugee arrivals), and even volunteering to be part of the ‘Welcome Dinner’ project (an Australia-wide phenomenon that aims to connect ‘established’ Australians to new ones of varied descriptions). The phenomenon of resistance via eating or cooking together is certainly not confined to Australia. Since the election of Donald Trump in the US, many groups are organising to share food with their neighbours, immigrants and refugees. One such group is the ‘Syria Supper Club’ in northern New Jersey which organises weekly dinners, where Syrian refugees break bread with people in the area who sign up online.

According to the Refugee Council of Australia, ‘As of 31 May 2016, there were 658 people (including 317 children) in community detention and 28,329 people living in the community after the grant of a Bridging Visa E.’ Since December 2014, those on the above bridging visas are eligible to work, but there are difficulties in timely renewal of visas, as well as practical barriers to employment. Despite being documented to have negative impacts on health, wellbeing and settlement outcomes, temporary protection visas were re-introduced in December 2014, with the added provision that those who are found to be in need of protection after their initial visa expires are not able to apply for permanent residency. This means an inability to engage in education and training.

Due to the above changes, it becomes imperative to understand how humanitarian migrants can no longer be seen as the harbingers of the previously-celebrated ‘ethnic enterprises’ and ‘small businesses’ that are icons of migrant enterprise and resilience in mainstream discourses. We are now much more likely to see well-meaning inner city hipsters setting up a café to offer hospitality training to young refugees with meager employment prospects, than to witness a mushrooming of new Afghani and Sudanese restaurants in suburbia. This is not to say that people seeking asylum have somehow become less resilient, but to unpack why we need them to be so in a time of increasing socio-political precarity.

In addition to legal and policy changes that impact refugees, that have prevented them from entering the workforce and /or the small business sector, there has also been a gradual diminishing of non-profits that provide critical services to humanitarian migrants. According to research, this is not just due to shrinking fiscal support in the form of public funds and donations, but also because of pressure from for-profit organisations, declining volunteer support, and the loss of commitment from non-profit employees.

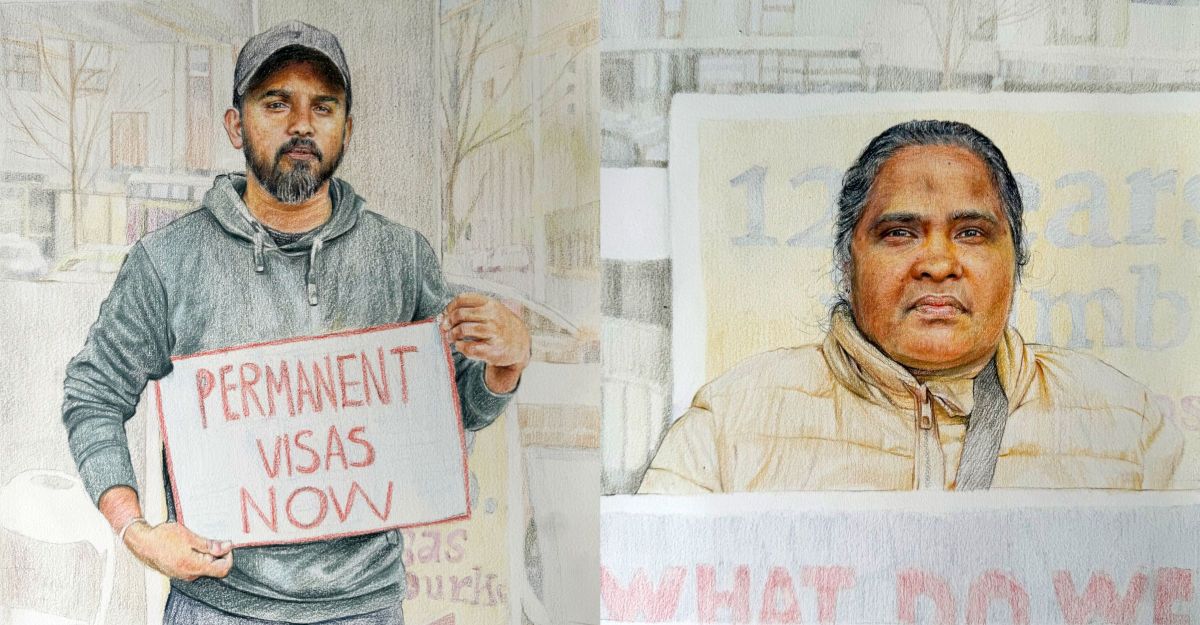

So how are refugees who have resettled in the community, as well as those endlessly waiting for their claims to be processed, coping? Can we put these coping mechanisms under the umbrella of ‘resilience’? Wouldn’t this merely provide us shelter from our own affective discomfort? Refugees in precarious conditions are not being served by the discourse of ‘resilience’ that is employed by both sides of politics to sell the idea that certain kinds of migrants are more socially and economically beneficial. This implies that those who act in the manner of ‘model minorities’ and demonstrate high levels of social capital by, amongst other initiatives, starting ‘ethnic enterprises’, are considered to be successful, even desirable migrants. What we need instead is an examination of the structural contexts that lead to such distinctions, and for the wider public to be aware of how conditions have progressively worsened for humanitarian migrants.

After first reading about the social enterprise aspect of Parliament on Kin online, I attended two ‘family dinners’ there prepared by former refugees. In addition to training people in barista skills, food preparation, food hygiene and service, the family dinners were initiated to take away the ‘otherness of being a new arrival’ (Dupleix, 2016). Both dinners I was present at were busy and possibly over-subscribed, especially given that the café consists of owners Ravi and Della Prasad’s living room facing on to bustling King Street in the inner-west suburb of Newtown. A few months later, speaking with Ravi in the same space, I discovered that he extended the hospitality-training model of the café after realising that the refugees were far from ‘deficient’:

The idea of the dinners occurred to me when I asked one of the former refugees training here what they do, and he said, ‘I used to be an eye surgeon’. Others said they were engineers or architects. I thought these people are so much smarter and brighter than me, and I’m teaching them how to make coffee, and here’s what jaffle is.

Ravi narrated the above series of stories of underemployment as being pivotal in convincing him to shift the dynamic, such that ‘instead of teaching them how to make toast’, he thought ‘let’s do dinner and invite the community.’ The process of organising the dinner itself, and deciding what was cooked and how, is in turned described as giving the reins to former refugees:

What are we going to cook? It will be your food, your way. You tell us what to do, where to buy it, how it’s going to be prepared. You are now in charge, you are my boss. You tell me what you want me to do. I can facilitate that for the guys. All the money earned from the dinners goes back to the asylum seekers. Also, the relationship changes as they are in charge.

Therefore, in the case of the family dinners, Ravi sees his role as that of the ‘facilitator’ rather than the ‘boss’, with the refugee or former refugees themselves welcoming customers into the café space, bringing food out, and mingling. This means they are no longer swinging between the polarities of being either treated as lacking, or seen as unrelentingly resilient. The cooking, managing and mingling is a means to render normality, however transient, to their presence in our communal spaces.

In a similar spirit of sharing food, collaborating, and facilitating natural conversations, Melbourne’s Dori Ellington started ‘Tamil Feasts’ with four Sri Lankan refugee men in 2015. Before two of them (Sri and Nirma) were released from Broadmeadows Detention Centre, Dori had been visiting them for over a year, and they had frequently greeted her with traditional Tamil fare like curries and bhaji. The team decided to begin with two Tamil dinners at the community kitchen of the Centre for Education and Research in Environmental Strategies (CERES), which is a non-profit, sustainability centre located in the suburb of Brunswick in inner Melbourne. These dinners were sold out within a week, and the idea soon expanded to having communal feasts three times a week, as well as a catering branch. In my phone interview with Dori, she cited the large number of local community volunteers as vital to the enterprise, and added that ‘the reason people volunteer is because it is a casual way to get to know and support refugees.’

When I visited Tamil Feasts and met the four men in April this year, they testified to how significant the friendships with the volunteers had become. Not only are they being connected to lawyers to assist with their still-unprocessed claims, but also the social support is vital to continue to have faith in a nation that seems to have turned against them. Their resilience, it seems, is a reflection of the efforts of their allies and advocates.