Not one known for clever rhetoric at the best of times, you could almost feel the self-congratulation oozing through President Trump’s attempt at the pun in that infamous tweet about the preexisting agreement between the US and Australia to ‘swap’ refugees:

Do you believe it? The Obama Administration agreed to take thousands of illegal immigrants from Australia. Why? I will study this dumb deal!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 2, 2017

What is striking about this message is how it captures the current ability of those in power to so swiftly dehumanise those seeking asylum around the globe.

Sure, the arrangement to exchange a number of those trapped in Australia’s offshore detention centres for some of the US’s Central American refugees being held in Costa Rica doesn’t make sense: why not just assimilate those seeking refuge in our respective countries ourselves? Yet the chess-game that this ‘dumb deal’ represents highlights leaders’ problematic ability to treat the vulnerable as pawns in political maneuvering, rather than recognise their right to empathy, inclusion and safety. Whether the deal is done or dumb, it seems politics is hyper bent on exploiting the defenceless for conservative votes, real or imagined. As a result, all over the world, refugees and asylum seekers are at the mercy of a series of craven and/or villainous bureaucrats and ministers. (See Immigration Minister Peter Dutton’s recent comments on the fate of 7500 asylum seekers in Australia: ‘If people think they can rip the Australian taxpayer off, if people think that they can con the Australian taxpayer, then I’m sorry, the game’s up.’)

In the first episode of The Messenger podcast, ‘Aziz, Not a Boat Number’, Manus Island asylum seeker Abdul Aziz Muhamat describes the dehumanising effect not being called by name has:

Three years I never heard someone who’s calling my name. I been calling with the numbers and letters. QNK002 … Numbers and letters. Three letters and three numbers, three letters and three numbers, for the last three years … My parents, they sacrifice for me to have this name. Not to have the boat number. Which is not to have these three numbers … Yeah, the name that I should have is Aziz. Aziz, not a boat. Not a boat number. Like QNK002.

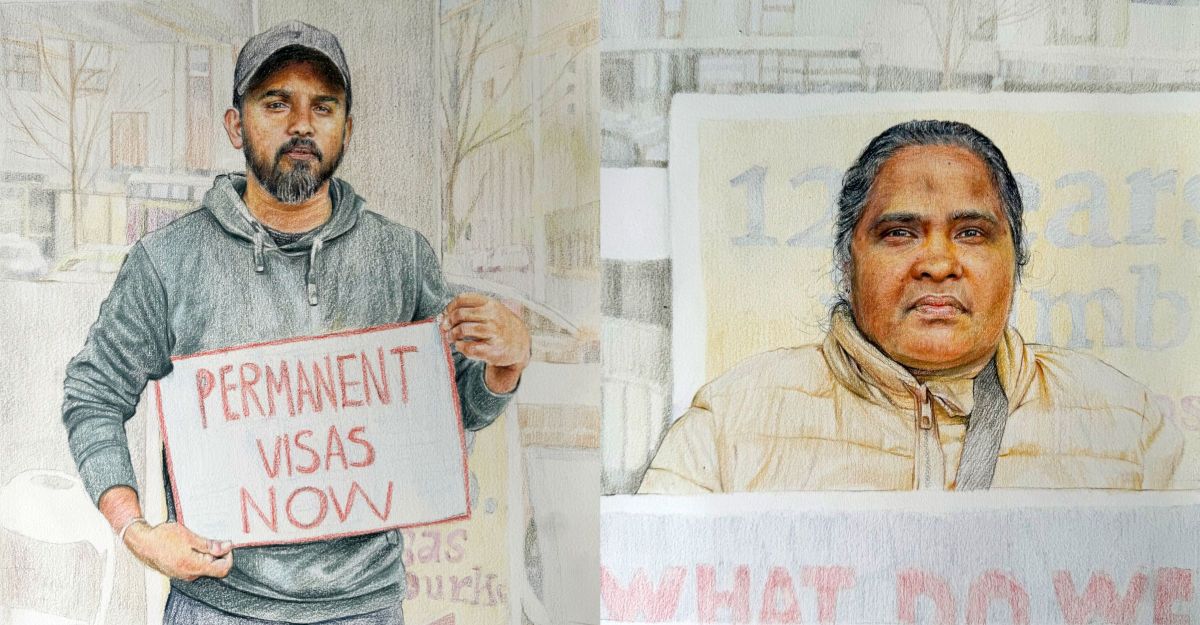

Of course, the labelling of people by number, not name, is an eerie throwback to events that history has condemned, and it’s unsettling that such cruelty is being repeated. Referring to asylum seekers by number is symptomatic of the anonymity that governments rely on: if they don’t have names and identities, then it’s easier to paint refugees and asylum seekers as monsters or bludgers or, at the very least, less than human.

Even accessing information from inside Australia’s torturous detention centres is notoriously difficult; for journalist Michael Green, contact with Aziz was a rare find. Though the use of phones was eventually permitted on Manus over the course of their interaction, Green points out that ‘under Australian law, even the guards and other contractors who talk publicly about conditions at the centre could be sent to gaol for up to two years. For the men in detention, like Aziz, the risks are harder to measure.’ Pretending that there’s nothing to see here – and punishing those who suggest there is – is allowing ‘dumb deals’ to go unchallenged, to be put in place, to proliferate.

As many people already know, trawling through Trump’s twitter feed is bleak: there is a lot of caps-lock yelling and alarming stabs at global diplomacy. What particularly stands out is the sensationalist language that can brand all asylum seekers as illegal or potential Boston Bombers. Distrust of the migrant isn’t anything new, but the blatantly racist and exploitative language of Trump, or event the Australian government, seems to be gaining traction it hasn’t had in decades. How is it that instead of being laughed at, Pauline Hanson and kin are gaining popularity? How is it that Dutton’s lies about the cause of the Good Friday shooting on Manus went largely unquestioned? How is it that we’re facing the greatest refugee crisis of our time, yet, nations are reinforcing walls?

These are questions don’t necessarily have easy answers. But a first step is to remind political leaders at every chance we get that they’re actually talking about people – individuals who our governments are incarcerating and endangering indefinitely. We also need to pressure our media so they ask hard questions and point out the lies rather than repeating slogans or giving airtime to clear fallacy. Lambasting truth as fake news needs to be disparaged, not laughed off.

We’re witnessing one epic chess game where countless innocents are shuffled around a board in a gross wrestle for power, and we need to change the rules so the shuffling stops.