The most disturbing aspect of viewing Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers, half a century after its release, is how familiar the images of Western soldiers involved in a civil conflict in an Arab country now feel.

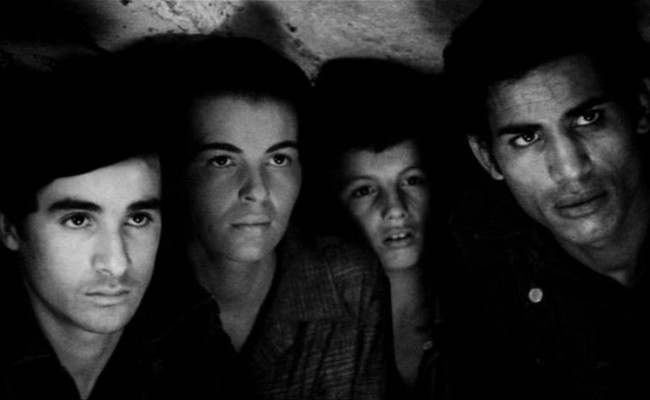

The strange sense of familiarity kicks in from the very beginning. In a small, dingy cell, white men in military uniform stand over an Arab male. His traumatised expression tells us he has been tortured. That he has given his captors information against his will shows in the shame etched on his bruised features. His captors dress him in uniform and take him along to raid an apartment block, no doubt based on the information he revealed. The soldiers identify a hidden section in one of the apartments where two men, a woman and a child hide. The soldiers wire it with explosives and threaten to detonate unless those hiding surrender.

The strange sense of familiarity kicks in from the very beginning. In a small, dingy cell, white men in military uniform stand over an Arab male. His traumatised expression tells us he has been tortured. That he has given his captors information against his will shows in the shame etched on his bruised features. His captors dress him in uniform and take him along to raid an apartment block, no doubt based on the information he revealed. The soldiers identify a hidden section in one of the apartments where two men, a woman and a child hide. The soldiers wire it with explosives and threaten to detonate unless those hiding surrender.

A decade and a half of reportage on the West’s military involvement in the Arab world, particularly post the mass circulation of images from Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay and their pop culture reflection in countless movies and television series, give Pontecorvo’s chilling iconography of civil strife and military repression an almost everyday feel. Anyone who follows the news has seen images of barbwire checkpoints, where nervous soldiers oversee Arab civilians; has seen images of detainment and torture, or traumatised and bloodied civilians in the aftermath of another bombing.

Released 8 September 1966, The Battle of Algiers is set amid the civil conflict in Algeria that ran from 1954 to 1962. The story is told from the perspective of supporters of the pro-independence Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) and representatives of the French state keen to maintain control over the country after the failure of its recent war in North Vietnam. The focus is the first stage of the struggle, 1954 to 1957, when FLN operatives infiltrated the Kasbah, the centre of the capital, Algiers, and began to organise the population. They are met with fierce repression, first by colonial police; then, when they prove unable to contain the conflict, French paratroopers, many of them veterans of the first Indochina war. The French successfully crush the initial rebellion, although a coda at the film’s conclusion informs the audience the colonial authorities were finally driven out and Algeria gained independence on 2 July 1962.

The two contrasting viewpoints – Algerian nationalism and French colonial authority – are epitomised by the characters Ali La Ponte (Brahim Haggiag) and French paratrooper leader Colonial Matthieu (Jean Martin, one of the few professional actors). La Ponte is an illiterate street hustler (and one of the men we see hiding from French troops at the beginning of the film); politicised after a stint in jail, he becomes a key FLN figure upon release. Colonial Matthieu (modelled on the infamous real-life ultra-right French paratrooper general Jacques Massu) understands the intelligence gathering and ideological aspects of his operation against the FLN are just as important, if not more so, as the military activities.

That the film is still potent, despite so much of what was once so shocking about it now forming part of our post September 11 routine, derives partly from the way Italian-born Pontecorvo imbues the work with a pseudo-documentary look and feel. The grainy black-and-white images have a grim, unnerving reality, showing the influence of Italy’s home-grown tradition of Neorealism – which includes films such as Roberto Rossellini’s Rome Open City (1945) and Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948), reactions to the studio-bound, Hollywood-influenced productions that dominated during the country’s Fascist period. Pontecorvo intersperses the film with a narration comprised of political communiqués and media commentary, giving it a newsreel quality, so much so when it was first shown in the US, the distributor felt obliged to add this message at the beginning: ‘Not one foot of newsreel footage has been used.’

But the film’s real power comes from its unflinching and deeply political examination of resistance to colonialism; it is almost unimaginable that a Western filmmaker would countenance such a depiction today.

The Battle of Algiers was not the film Pontecorvo and his communist fellow traveller and co-screenwriter Franco Solinas (who worked on the Costas-Gavras’s 1972 Neorealist classic, State of Siege) initially intended to make. While both men wanted to make a film commemorating the popular uprising in Algeria, they initially wanted Paul Newman in the lead as a former paratrooper, turned magazine reporter, covering the independence conflict.

We can only speculate what that film would have looked like – probably something akin to Lost Command, Hollywood’s take on the Algeria conflict, released the same year as Pontecorvo’s effort and starring Anthony Quinn, Alain Delon and George Segal (the latter playing the leader of the Arab insurgents). Lost Command has aspects in common with The Battle of Algiers, but focuses on Quinn as the veteran leader of the French paratrooper forces in Algeria, given one last chance to prove his military worth – and salvage his wounded pride – after unsuccessfully commanding French forces at Dien Bien Phu.

Pontecorvo and Solinas took a different tack after a visit from a representative of the new government in Algeria, who told them FLN leader Saadi Yacef had written his own script based on the Algerian conflict and was seeking a suitable director. Pontecorvo and Solinas travelled to Algeria and over the course of their visit, came up with a new script, not exactly the story envisaged by Yacef (who, nonetheless, would help produce and starred in The Battle of Algiers), but neither the Western-centric, mainstream melodrama they originally envisaged.

While The Battle of Algiers looks at the conflict from two sides, it is unambiguously pro-FLN and was the first feature film to depict North Africans as complex, multifaceted characters. It is an objective portrayal of the Algerian conflict – not in the anaemic sense the term has come to mean, but as a detailed, almost forensic study of the racism and violence permeating colonialism and what had to be done in the context of the early 1960s to successfully fight occupation.

Tellingly, the term ‘terrorism’ is not used in the film, but the story does not shy away from the mechanics of political violence, how it is organised and its impact. The gradual escalation of shootings and bombings, by both the FLN and the French, is interspersed with a frank depiction of conflicting tendencies within the FLN: moderates versus hardliners. That the Algerian resistance and the French are not militarily equal is clearly signposted by the desperate measures undertaken by the anti-colonial forces.

One of the film’s most compelling sequences depicts women members of the FLN dropping their veils and assuming a modern Western look in order to infiltrate the capital’s European Quarter, where they plant bombs in two cafes and an Air France ticket office. In a café full of French civilians, the camera lingers on the patrons before and after the blast. Whether it manifests in torture or a bomb blast, Pontecorvo does not romanticise violence and its impact on fragile bodies, Arab or European.

In France, where the Gaullist government was still smarting from its defeat in Vietnam, The Battle of Algiers was banned upon release until 1971, and censored in the US and UK. Despite these moves, the film’s appearance during a time of massive anti-colonial sentiment in the South and a growing student movement in the West, a minority current of which supported armed struggle, ensured an avid audience. It was rumoured to be the favourite film of Baader-Meinhof leader, Andreas Baader, and celebrated as a how-to guide of sorts for numerous guerrilla groups, including the Irish Republican Army and the Black Panthers. Its aesthetic and style has influenced two generations of politically engaged film directors, including Ken Loach, Spike Lee, John Sayles and Oliver Stone.

The film’s message cut both ways. Its counter-insurgency lessons resulted in it being shown to military cadets in Argentina’s infamous Navy Mechanics School, the site of an illegal and secret detention centre during the military dictatorship’s ‘Dirty War’ (1976–1983). In 2003, the Pentagon screened The Battle of Algiers for officers and civilian experts, as part of an education session on the challenges facing US forces in Iraq, to show how it was possible to win a war militarily but lose the battle for hearts and minds.

Image: Still from The Battle of Algiers.