‘My government stands absolutely ready to look after the people who are due to be sent back to Nauru – we stand ready, willing and able to do that.’

If you knew nothing of Australian politics, but were aware of the asylum seeker crisis on Nauru, you might attribute that bold statement to the exciting new Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, a cosmopolitan conservative who insists his government is treating the 267 asylum seekers who may return to detention on Nauru with ‘compassion’. Of course, you would be wrong, as the statement belongs to Queensland premier Annastacia Palaszczuk, one of several state leaders calling on the federal government to ‘Let Them Stay’. Yet Turnbull – elected to the leadership on the hope of a change in style, not substance – is having none of it: granting asylum to the 267 detainees is sending the wrong signal to people smugglers, he claims, as if you could control their actions with incentives and disincentives.

That position is anathema to parts of the public, and even parts of the political class, as doctors refuse to discharge children who may face deportation to Nauru. But, as the public campaign to let them stay intensifies, an international life-line is emerging for both the asylum seekers and Malcolm Turnbull. New Zealand’s conservative Prime Minister John Key is indicating that his country’s offer to accept 150 refugees a year from Australia’s immigration system still stands and could include taking some, or all, of the 267 asylum seekers. The offer reflects the general paradox in New Zealand’s approach to refugees and asylum seekers: in a theoretical sense, it looks and feels comparatively generous, yet in a concrete sense it’s not nearly enough.

The 150 asylum seekers – or 267 if Immigration New Zealand accepts each person’s claim as legitimate – will only form part of New Zealand’s miserly ‘quota’ of 750 refugees per year, not an addition to it. While international observers often applaud the country’s generous approach to refugee and asylum seeker laws, like its wide interpretation of ‘racial persecution’ under the Refugee Convention, of the approximately 350,000 residence visas Immigration New Zealand grants each year only 750 are granted under the refugee and asylum seeker category. Key is under pressure to lift the quota, but refuses to do so, instead favouring one-off exceptions for refugees fleeing the conflict in Syria and one-off offers for detainees returning to Nauru.

A cynic might accuse Key of making an offer that he knew Turnbull would refuse, a diplomatic tactic to take the domestic high ground. But it works both ways: Key is under tremendous pressure from his left to lift New Zealand’s quota for the first time in twenty-nine years, while Turnbull is under pressure from his right to act tough (to keep the border secure). It’s a move right out of Key’s political playbook, one that Turnbull studies closely (in a private chat with President Obama Turnbull identified Key as ‘a real role model’). Whatever happens to the offer, both Key and Turnbull can claim they’re acting. The only question is for whose benefit: the right; the left; or asylum seekers?

The answer for that depends on their domestic political situations. The secret to Key’s success is that he exhausts the social forces to his left, from lifting benefits for families on state support (thus taking the energy out of the anti-poverty campaign) to one-off changes to the refugee quota. To true believers on the right, this looks like treason, but it’s done for their benefit. Governing from the left helps maintain the right’s political hegemony. The change to benefit levels (the first in thirty years) might feel progressive, but it came with strict work obligations (and followed a significant attack on workers’ rights).

Key is doing Turnbull a similar favour, putting trans-Tasman mateship to work and offering him a chance to govern from the left to exhaust the growing ‘Let Them Stay’ movement. Say Turnbull does accept the offer, the Australian movement for refugees and asylum seekers loses the public faces it has tethered itself to, yet even if Turnbull refuses he can still spin the situation to his benefit. ‘I’m making a hard-headed decision,’ he can say, ‘and I’m choosing to keep the border secure.’ For asylum seekers, this decision would be devastating, and surely the preference is for relocation to New Zealand.

As a New Zealander, I think the campaign should support Key’s offer, yet it must be wary of how such a decision could take the energy out of the campaign and help cement the current government’s detention policy. Were relocation to happen, it would look and feel like a win for the campaign, yet the policy problem would remain. And as New Zealanders, we must be equally wary of how Key’s offer does something without dealing with the problem. Under questioning in Parliament Key admitted that detaining children isn’t in and of itself inhumane, and he won’t raise the issue of detention when he meets with Turnbull, perhaps signalling that more than humanitarian sentiment and trans-Tasman mateship is at work here.

—

If you liked this article, please subscribe or donate.

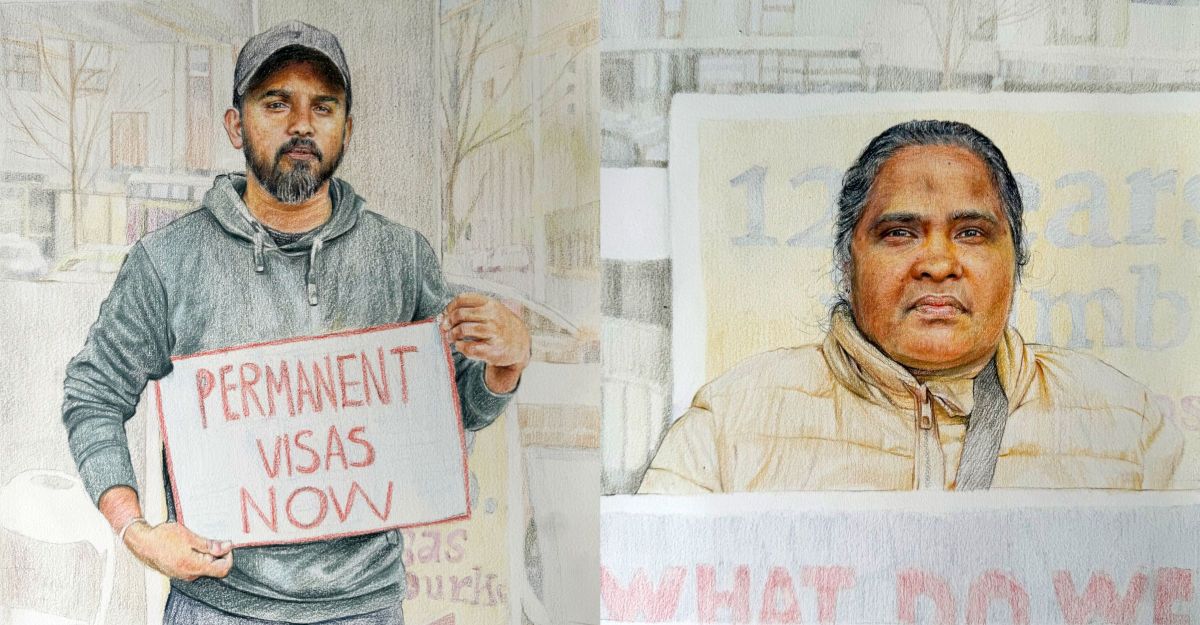

Image: Patrik Nygren/Flickr