In October 2013, the right-wing journal Quadrant published the book Australia’s Secret War, an account by Hal Colebatch of homefront industrial disruptions by Australian trade unions during the Second World War. Described as a secret history rescued from ‘folk memory’ – and one previously suppressed by leftists – it detailed ‘treacherous’ industrial actions by unionists that denied/delayed vital war materials to the frontlines between 1939 and 1945, resulting in the deaths of service personnel. These actions, the argument went, pointed to a deliberate and coordinated attempt at sabotaging the war effort courtesy of the communist leaderships of the unions involved. Maritime unions, in particular the Waterside Workers’ Federation (WWF), were the focus of the book.

Aided by the vituperations of Alan Jones on the airwaves and Miranda Devine in the Murdoch press, the book quickly transmuted from niche to reprint with mainstream national release and distribution for the Christmas market. Quadrant editor and publisher Keith Windschuttle effusively praised the book in the December issue of Quadrant. David Flint followed in the January issue with a lengthy review in which the words ‘evil’, ‘treachery’, ‘crimes’, ‘traitors’ and ‘insidious’ were used to describe wartime waterfront industrial disputes. Flint expressed his wish that martial law had been instituted on Australian wartime waterfronts to curtail wharfie industrial actions, and regarded the alleged American use of submachine-gunfire and stun grenades on the Adelaide waterfront in 1942, during an incident allegedly involving the mishandling of an American military cargo by Australian wharfies, as reasonable.

Colebatch makes significant use of interviews and correspondence with alleged participants, or those at a remove from the action being examined. It is the sort of material which Windschuttle has persistently disclaimed in relation to the Australian Indigenous histories – and it’s notoriously suspect regarding authenticity and problems associated with misremembering and the anecdotal. Specialist scrutiny by ‘war history’ enthusiasts has raised serious questions about Colebatch’s sources, evidence, and facts.

Despite Colebatch’s claim to the contrary, industrial disputes and unrest in Australian wartime industries and worksites have been canvassed by scholars of industrial relations and labour history, as has the existence of the many strikes and industrial actions on Australian waterfronts during the war. What Colebatch and his supporters seem unable to countenance is what the scholarly literature clearly establishes: that wartime industrial actions by waterfront workers were primarily local in origin, variously based on local factors and understandings, and occurred despite attempts by the communist national leadership of the WWF to curtail them.

Colebatch fails to grasp the realities of a complex context and industry: a national trade union leadership, in wartime, based in Sydney, overseeing a large national membership organised in some 50 or so port-based branches dotted around a huge coastline. Each had their own leaderships, distinct histories, cultures, politics, practices, port characteristics, infrastructures and work demands. Furthermore, the WWF rank and file were far from being communists during that war or the Cold War. In actual fact, they tended to be ALP members or sympathisers – the interesting point being they supported communist leaderships through to the 1960s because these were seen to deliver the goods so far as industrial relations were concerned.

Colebatch and his supporters work on the premise of a patriotic, all-pull-together, seamless Australian homefront war effort between 1939 and 1945, in which industrial unrest was a perverse and isolated presence. A comfortable myth, but the reality was otherwise. For example, when Australia and Japan went to war, the Labor government thought it necessary to cajole a confused civilian population with a barrage of racist propaganda to counter complacency created by a decade of appeasement of Japanese militarism by previous conservative governments and profitable trade relations with Japan developed by Australian capitalists. When Darwin was bombed by Japan in February 1942, there was large-scale desertion by Australian service personnel, and looting and thuggery by both civilians and servicemen; subsequent critical findings of a Royal Commission were kept secret until 1945. Australian media interests united in 1944 to defy Commonwealth war censorship laws, resulting in police intervention and, on one occasion at least, a drawn police revolver.

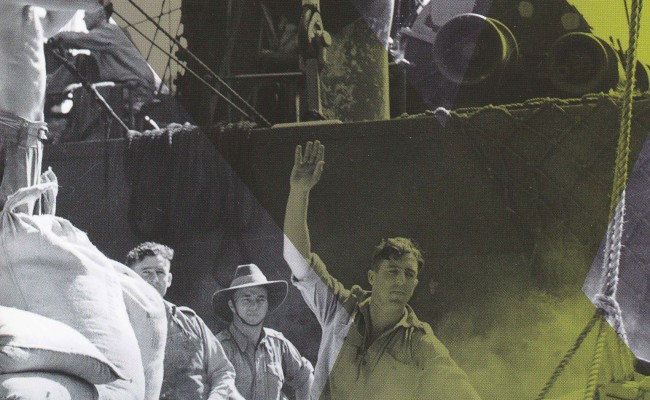

Colebatch has maritime workers in his sights as a collective, and while making mention of the Seamen’s Union of Australia (SUA), possibly the most communist of Australia’s wartime unions in terms of leadership and rank and file membership, but he focuses on the wharfies instead. This enables the wartime contribution of SUA members to be ignored. Between 1939 and 1945, Australian merchant mariners suffered high losses – at least 288 were killed by enemy action – with much of the toll in Australian waters due to enemy mines, and submarine and air attacks. Hardly a treacherous or inconsequential civilian contribution to the war effort.

Judging from reviews and online comment, Colebatch’s book is being used to suggest a curious case of responsibility and heritage: the actions of the wartime unionists were treasonous and the culprits never brought to book; their attitudes were such that they considered themselves above and beyond the common good – a sense of moral superiority that still characterises their modern counterparts (either the trade union movement generally or, specifically, maritime workers now organised in the Maritime Union of Australia).

Colebatch has form, as they say in the classics. He is the third son of the short-term (one-month) twelfth premier of West Australia, who accompanied strikebreakers onto the waterfront during the bitter Fremantle wharf crisis of 1919, an inflammatory action which contributed to the death of trade union loyalist Tom Edwards following a police battoning. In many ways Australia’s Secret War is a pioneering contribution to the new ‘anti-leftist’ history of Australia as envisaged by the Abbott government’s Education Minister Christopher Pyne, and an ideological contribution to the Abbott government’s looming war against the Australian trade union movement.