During a recent mandatory training session titled “Respecting the Difference: Be the Difference,” I sat in a quiet room while the facilitator, with a calm and soothing voice reviewed the history, struggles and consequences of settler colonialism on Australia’s Indigenous population.

I had considered delaying attending the session until next year — when I might have more emotional distance from the content — but decided to sit with the discomfort. As an Australian-born woman of Palestinian heritage, I felt the parallels between the experiences of Indigenous people in Australia and my people in Palestine were impossible to ignore. Watching Palestinians endure escalating violence this past year —on top of more than seven decades of occupation and apartheid — has made the reality of colonial oppression feel deeply personal and painfully relevant.

As I listened, I found myself reflecting on the persistent injustices faced by Indigenous people in Australia, especially children, and the enduring legacy of these policies. The conversations felt distant for some attendees, underscoring how little public knowledge exists about the lasting impacts of colonisation. This ignorance, I realised, enabled harmful policies to continue, both in Australia and in Palestine. It also echoed the global silence surrounding Palestinian children detained under Israel’s military occupation, an issue largely hidden from mainstream discourse.

The colonial legacies in Australia and Israel share stark similarities, especially in how children are disproportionately targeted by systems of incarceration. In Australia, Indigenous children represent 50 per cent of incarcerated youth, despite comprising only 6 per cent of the population. Instead of addressing the root causes of this overrepresentation, the Northern Territory government recently lowered the age of criminal responsibility to ten years old. In defence of this policy, Country Liberal Party Chief Minister Lia Finocchiaro stated that

by lowering the age of criminal responsibility, we can intervene earlier in a young person’s life and provide them the support they need to turn a new page, including through our promised two new youth boot camps in Darwin and Alice Springs.

While Finocchiaro frames this policy as an opportunity for early intervention, the underlying logic bears troubling similarities to the policies of the Stolen Generations. Then, too, state intervention was justified under the guise of “helping” Indigenous children by removing them from their families and providing them with education and training to assimilate into white society. The promise of “support” through youth boot camps today echoes the assimilationist rhetoric of the past, where forced removal was framed as a necessary step to ensure a better future. Just as the architects of the Stolen Generations sought to “improve” Aboriginal children by severing their cultural ties, these new policies risk reinforcing cycles of disadvantage by criminalising children instead of addressing the root causes of their struggles.

In ways that are often starkly similar, Palestinian children have been a central target in Israel’s ongoing occupation. Today, increasing numbers of Palestinian children are held in military detention facilities, with 500 to 700 children prosecuted annually. Over the past twenty years, an estimated ten thousand children have been arrested under Israel’s military laws. As of November 20, 2023, 880 children had been detained that year alone, the majority for minor or unknown offences.

Palestinian children are subjected to military courts with close to 100 per cent conviction rates — the only children in the world prosecuted systematically in this way. Reports by Save the Children reveal the brutal conditions these children face: 86 per cent are beaten while in detention, 69 per cent are strip-searched, and 42 per cent are injured during their arrests. This military legal framework applies only to Palestinians, while Israeli settlers in the same territories enjoy the protections of civil law, reflecting the structural inequality that underpins the occupation.

The parallels between these two contexts are unmistakable: both Australia and Israel use detention systems to disrupt and control future generations. In Palestine, children are detained as a means of maintaining the occupation and suppressing resistance. In Australia, youth incarceration extends the legacy of forced removals and perpetuates intergenerational trauma among Indigenous communities. These policies fragment families, weaken social bonds, and inflict long-term psychological harm — mirroring the damage inflicted on children removed from their families during the Stolen Generations. Children are targeted precisely because they represent the continuity and survival of their communities. This intentional disruption is not simply a matter of misguided policy but part of a broader effort to undermine Indigenous and Palestinian resilience.

The persistence of these policies is, at least in part, fuelled by the lack of public awareness and understanding. This silence reinforces the notion that these issues belong to the past, rather than being ongoing realities. Breaking these cycles requires more than incremental reforms. For real change to occur, public awareness must move beyond isolated moments of mandated training sessions or governmental reports. Ignorance is not neutrality: it is complicity in ongoing oppression.

For Australia, raising the age of criminal responsibility and investing in culturally appropriate interventions would be necessary first steps toward dismantling the legacy of the Stolen Generations. However, the real challenge lies in addressing structural racism and historical injustices that continue to fuel these policies. In the case of Palestine, true progress demands ending the military detention of children, but more importantly, the occupation itself must end, as it not only sustains the cycle of violence and detention but also impedes any meaningful path toward justice and peace for future generations. Dismantling these colonial systems is essential to nurture children, restore communities, and break the cycles of trauma that have persisted for decades in the two contexts.

Both the Australian public and the global community must confront the realities of these injustices and challenge the systems that criminalise and control children. The struggles of these young people are not isolated issues but part of a broader narrative of resistance against colonial domination. Recognising the parallels offers valuable insights into the mechanisms of control and underscores the urgent need to “be the difference” by challenging these systems of oppression. Only by acknowledging these harms and addressing the root causes of these systemic inequalities can we build a future where children are nurtured and supported, not bombed or incarcerated.

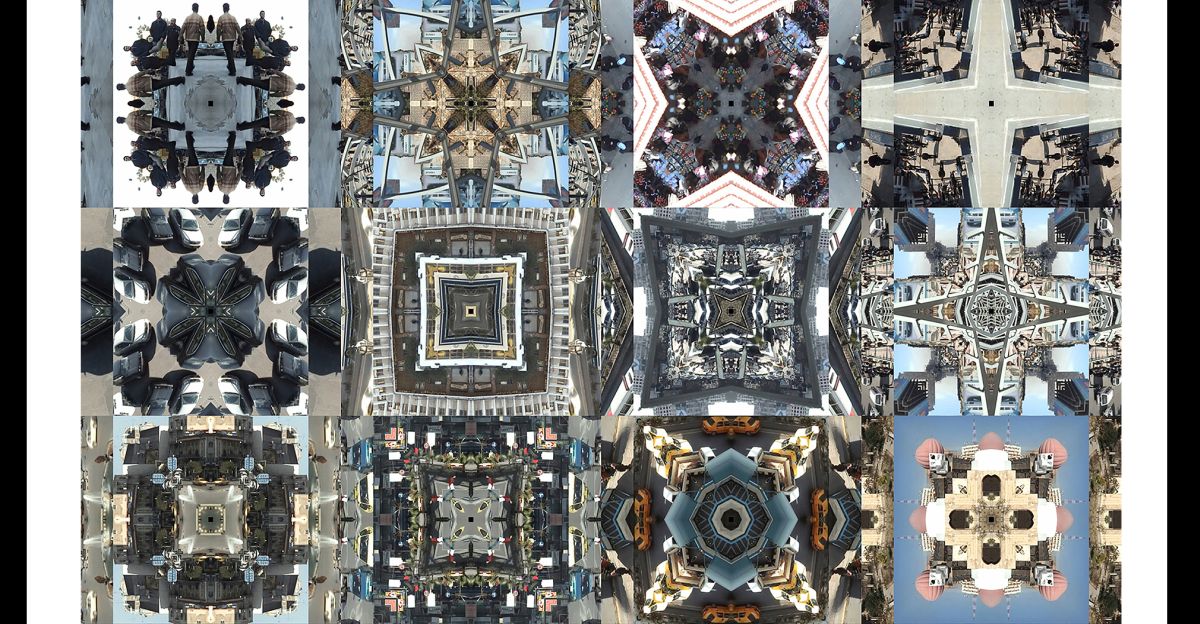

Image: Wasfi Akab