What role should unions and the left play when it comes to fighting unemployment and underemployment? With both the Albanese Labor government and Reserve Bank of Australia publicly advocating higher unemployment to bring down inflation, it’s a question that gets surprisingly little attention.

Consider the current unemployment situation. According to government data, today there are 3.4 million people either unemployed, underemployed, or part of the “hidden unemployed” — up from 3.03 million when the Labor government took office in May 2022. Recent sluggish economic growth, the lowest since the recession of the early 1990s, suggests this situation is going to get worse before it gets better. While Labor Treasurer Jim Chalmers has tried to direct blame elsewhere — the RBA, a “global downturn”, the previous Morrison government — there is little doubt that the growing number of jobseekers is a deliberate policy choice.

As economist John Quiggin points out, soon after scraping into power at the June 2022 election the Albanese government frantically adopted Coalition policy in areas where Labor was perceived to have an electoral disadvantage — namely, economics, defence, and foreign policy (I would also add social services to that list). The result was that Labor’s pledge, made in Opposition, to never return to the business-as-usual mass unemployment economic agenda of the pre-Covid era was quietly shelved. A promised white paper on full employment never arrived.

Successive austerity Budgets were handed down, each outlining Labor’s plan to combat inflation by increasing unemployment to at least 4.5 per cent, a rate notably within half a percentage point of the prevailing pre-Covid level. The government’s failure to reach this “target” — the unemployment rate is currently sitting at 4.2 per cent, up from 3.5 per cent in 2022 — helps explain the government’s continued acceptance of the RBA’s punishing interest rate hikes which, according to Governor Michele Bullock, align with Labor’s objective of pushing unemployment up to 4.5 per cent. “The RBA wants to make 140,000 more people unemployed”, wrote Australian Institute economist Matt Grudnoff in 2023, “because they believe that unless this happens inflation and wage increases will not slow”.

At the same time, Labor has failed to offer much-needed support to the victims of its policy agenda. Calls to significantly increase the Jobseeker benefit — a payment $220 per week below the poverty line — have been consistently refused. Australia’s privatised system of employment services, which oversees compulsory activities like Work for the Dole, remains broadly intact. Every day, this notoriously punitive and under-funded system punishes unemployed workers for failing to obtain jobs that don’t exist: in the three months to June, it applied 433,934 payment suspensions across a cohort of around 650,000 unemployed workers.

Not for the first time, unemployed workers have become cannon fodder in the battle against inflation. To quote Jim Chalmers’ 2020 critique of the Morrison government: “On what planet does helping the growing ranks of the unemployed, in an economy starved of spending power, constitute holding the country back?”

These days Chalmers sings a very different tune. Last week, Chalmers announced Labor’s higher-than-expected $15.8 billion surplus for 2023-24 – up from the initial $9.3 billion estimate released in May – by telling reporters that “responsible economic management is a defining feature of the Albanese Labor government”. Business groups, having expressed a fear that the labour movement’s push for genuine full employment would “blow up the economy”, could barely contain their relief. Responding to Labor’s May 2024 surplus budget, the Business Council of Australia congratulated the Albanese government on the “positive steps” it was taking to make “Australia more globally competitive”.

Labor’s about-face on unemployment has increased the pressure on the union movement to act. On the face of it, the unions appear to take this responsibility seriously. Like Labor, for most of the pandemic the ACTU claimed it stood for abolishing unemployment. In 2022, ACTU submissions called on government to “make true full employment an explicit macroeconomic goal in the form of zero involuntary unemployment, ” noting the “moral indefensibility of leaving hundreds of thousands of workers involuntarily unemployed as a deliberate design feature of macroeconomic policy.”

More recently, last June the ACTU Congress passed a rare stand-alone motion declaring full employment as

the foundation of improving workers’ living standards, re-establishing the link between rising productivity and real wages, and reversing the decades long decline in the labour share of national income.

Pointing to “decades of neoliberal policies have led to an economy where workers have not shared in rising national prosperity”, the ACTU called on the government to increase Jobseeker to the “poverty line” and make full employment “the top macroeconomic and policy priority by government.

There has, somewhat predictably, been a substantial gap between words and action. Just as Labor rushed to adopt the Coalition’s economic policy in 2022, the unions have been quick to fall in line behind the Albanese government. Take, for example, the ACTU’s decision to unreservedly praise Labor’s May 2024 austerity Budget as “good … for working people.” A similar acquiescence occurred in September 2023 after Labor handed down a monster $22 billion surplus Budget, despite rising under/unemployment and cost-of-living pressures.

The unions’ lack of ambition is perhaps best exemplified by the ACTU-led Renew Australia for All (RAFA) coalition. Launched at Parliament House last month, RAFA is calling on Labor to make an initial $5 billion investment to install solar panels across Australia, thereby creating affordable energy and 18,000 new jobs. This is undeniably an important campaign and deserves public support. However, considering the ACTU’s staunch full employment policy statements, RAFA’s disengagement with Labor’s mass unemployment agenda is striking.

RAFA’s objectives appear very much in line with Labor’s insipid A Future Made in Australia platform and, by extension, Albanese’s 2025 re-election effort. As ACTU Senior Adviser on Climate and Energy Daniel Sherrell told RAFA’s online launch event, the favourable response from key Labor figures means the campaign will be “pushing on an open door.” The unions refusal to use the RAFA coalition to promote its full employment policy represents a missed opportunity.

It has been a similar story with the broader left. The Greens, for instance, have steered clear of campaigning on this issue in recent years. This timidity is particularly jarring considering that, soon after his election as leader in 2020, Adam Bandt told the National Press Club that “under my leadership, the Greens will be a party that champions full employment … which means we will fight for 2% unemployment — like it was on average between WWII and the 1970s.” As with the labour movement, however, these words have not translated into actions.

While Greens Economic Justice spokesperson Nick McKim recently took aim at the Labor government’s refusal to use its legislative power to push down interest rates — an important demand — McKim’s failure to connect this issue with Labor’s acceptance of mass unemployment was typical of the Greens retreat from the full employment policy debate. With both major parties floundering on the growing unemployment crisis — and the public favouring stronger government action on jobs — this represents yet another missed opportunity.

The socialist left, most notably the Trotskyist organisations that dominate contemporary Australian socialism, have shown even less interest. Socialist Alternative (SA), the largest of these organisations, appear largely oblivious to the growing unemployment problem. Its newspaper, Red Flag, virtually ignored the full employment debate, even at its peak during the 2020-22 period. While SA’s electoral arm in Victoria, Victorian Socialists, are formally committed to creating public jobs for everyone who wants one, this demand lacks visibility. The Socialist Alliance has adopted a similar approach.

At a time when left-wing movements in the UK, the European Union and the US are campaigning for governments to provide a “green job” to everyone who wants one, the Australian left is getting badly left behind. There is, however, some cause for optimism. In 2020, the emergence of a youth movement in Australia focused on fighting unemployment demonstrated, albeit briefly, what a back-to-basics approach to activism can achieve.

That year, amidst the lockdowns, two youth-based organisations formed with the explicit goal of eliminating involuntary unemployment: Young Labor for Full Employment and the Tomorrow Movement. While Young Labor for Full Employment focused on reforming Labor from the inside — significantly strengthening its full-employment policy in the process — the Tomorrow Movement sought to use extra-parliamentary activism to achieve its goal of a “climate job guarantee.” Under this “transformative plan,” everyone would be offered a “good union job” to do the work to “rapidly decarbonise every industry and rebuild resilience in our communities to ensure everyone is looked after.”

Unlike the unions and the established left, the Tomorrow Movement was not content with passing impressive-sounding resolutions. “With a Climate Jobs Guarantee”, wrote activist Josephine Foster in a 2021 Overland article, “we could address climate change and unemployment, with the benefits being felt immediately. The only thing left to do is fight for it.” By July 2022, a tireless organising effort led to around a hundred activists descending on Parliament House in Canberra demanding the newly elected Labor government introduce a Climate Jobs Guarantee. After a spirited rally that briefly occupied the foyer, activists were forcibly grabbed by police and thrown out. The following year, over 100 activists occupied Albanese’s electoral office calling for action. A new kind of unemployment politics was taking root.

The unions were not interested in the extra-parliamentary activism of the Tomorrow Movement. While the United Workers Union’s “Climate Action Groups” offered some initial encouragement, the union movement backed the Albanese government’s “small target” economic strategy. The skepticism of the union hierarchy toward a Job Guarantee-style policy was best expressed by Labor left figure and CFMEU leader Michael Hiscox, who in 2020 argued that it represented an attack on unions and their bargaining power, comparing it to the punitive Work for the Dole scheme “albeit with higher payments.”

These sentiments are not only at odds with the dominant literature on the Job Guarantee — Professor Bill Mitchell, who helped develop the idea in the 1990s, directly refutes this argument – they also betray a lack of genuine concern for unemployed workers. Indeed, when the public sector union launched its campaign opposing the privatised employment services system administering the actual Work for the Dole scheme — today, still Labor policy — neither Hiscox, his union, nor the Labor left were anywhere to be seen.

Lacking support from the established left, the early promise of this anti-unemployment movement has not yet been realised. While Young Labor for Full Employment disbanded in late 2021, over the past 12 months the militancy of the Tomorrow Movement’s Climate Jobs Guarantee campaign has receded and, at least on the face of it, has been replaced with the gentle reformism of the RAFA coalition of which it is a member.

The absence of a visible campaign against mass unemployment has had a profound impact on Australian politics. The idea that workers should — or even could — directly fight unemployment has been pushed to the fringes. Union and left-wing engagement with unemployment has, for the most part, become an increasingly top-down largely technocratic affair devoid of grassroots participation. As a result, unemployment policy is increasingly understood as something that happens to workers, rather than something that they can have a hand in creating. This, of course, is very good news for the austerity hawks who control the levers of the economy.

It does not have to be this way. While largely forgotten today, Australia has a rich history of workers fighting for full employment. In the decades following World War II, left-wing unions campaigned vigorously — and successfully — against unemployment whenever it crept above the unacceptably high rate of 2 per cent. These struggles helped Australia achieve an unprecedented period of full employment throughout the post-war period, much to the chagrin of employers.

The unions’ response to the Menzies Coalition government’s 1961 “credit squeeze” is a shining example of what extra-parliamentary struggle can achieve. In April 1961, as the unemployment rate approached 3 per cent, the powerful metal workers’ unions kicked into action. A Sydney convention of 150 shop stewards announced a major mobilisation in defence of full employment. “The right to a job”, the convention resolved, “is the inalienable right of all workers and therefore the immediate demands of this Convention are for the right to work … and a lift in the people’s standards.” It directed workers to take “political lines of action”, such as petitions and rallies outside parliament, in addition to job actions aimed at resisting retrenchments. A particular focus was placed on defeating the Menzies government at the upcoming 1961 federal election.

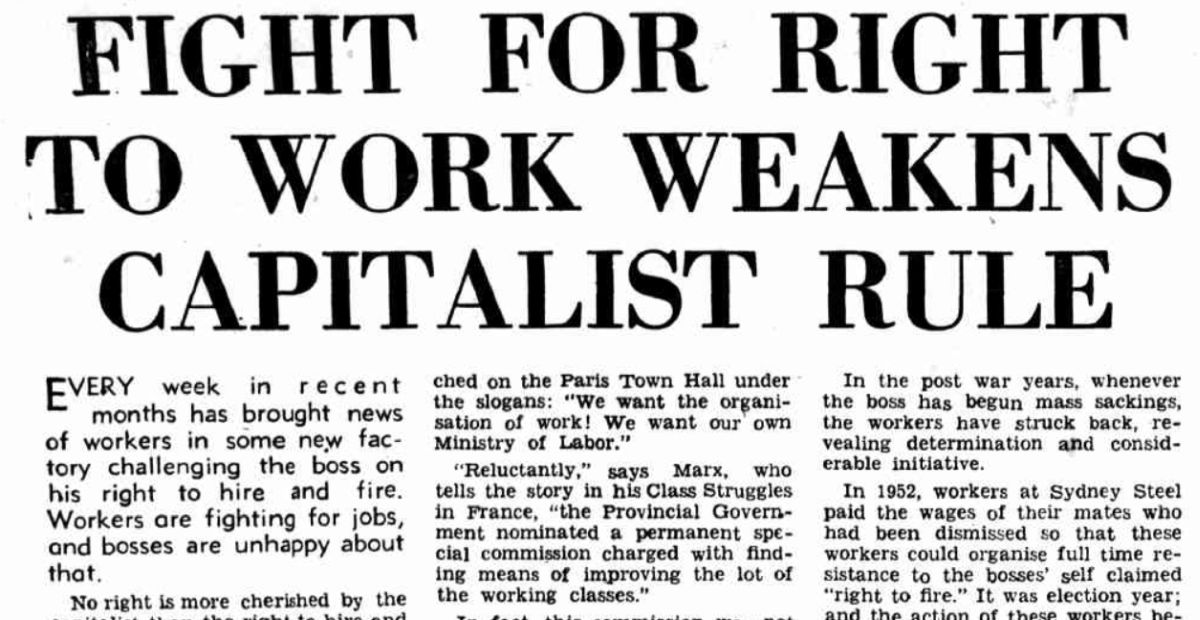

The Communist Party of Australia (CPA), which enjoyed significant influence within the metal workers’ unions, played a leading role. CPA and Sheet Metal Workers Union leader Frank Bollins urged workers to use the convention “as a base from which a mighty campaign can develop around the demands for the right to work.” The CPA national newspaper, Tribune, summarised the Party’s rationale:

In the post-war years whenever the boss began mass sackings, the workers have struck back, revealing determination and considerable initiative … This dispute is the most significant of all the myriad disputes that occur between capitalist and worker — because it goes right to the heart of the capitalist system — it challenges the very foundation of that system. Today, the monopolies lament almost daily in their newspaper that they are seriously hindered by the widespread determination to defend full employment.

Even the CPA’s enemies acknowledged the success of its right to work movement. Jack Lang, former NSW Premier and noted anti-communist, warned the Menzies government in May 1961 that its “calamitous economic policy…is creating the very conditions under which communism breeds and spreads its cancerous tentacles into the body politic”. “Unemployment”, he continued, ““is the condition promoting communism and making Communists out of citizens who have never previously had occasion to question the base of our social system and its government.”[1]

Lang was right. In the months that followed, an unprecedented wave of “right to work” protest actions swept the country, including a series of large deputations to Canberra, leading to a genuine groundswell of radical opposition to the Menzies government.

The strength of the post-war right to work movement was on full display at the 1961 ACTU Congress in September. Buoyed by the upsurge in the struggle against unemployment, Congress delegates called on the ACTU to coordinate a massive campaign in defence of full employment. In what is still the ACTU’s most militant campaign against rising unemployment, Congress declared its “determination to fight for the restoration of full employment for all Australian wage and salary earners” and requested “all State Trades and Labor Councils and Unions [to] assist in the fight for full employment”. Noting the upcoming federal election in December, Congress called on “the whole trade union movement to wage an enthusiastic campaign for the defeat of this [Menzies] Government and the election of a Labor government pledged to implement the foregoing [full employment] policy.”[2]

Thanks to this militancy, combined with the Arthur Calwell-led Labor Opposition’s laser-like focus on the Menzies government’s disastrous “credit squeeze”, Labor came from nowhere to within a few hundred votes of forming government. Menzies was left with little choice but to restore full employment and increase the unemployment benefit. For the rest of the decade, the unemployment rate averaged 1.5 per cent.

The post-war vigilance of the labour movement on unemployment shows that an alternative is possible. Most importantly, it should give encouragement to the new generation of unemployment activists to stay the course. Indeed, a key lesson lesson of the post-war “right to work” campaigns is that this sort of movement-building takes time. The CPA spent much of the 1930s, most notably during the Great Depression, building the foundations for the unemployment struggles to come.

Today, the worsening climate and unemployment crises means there is no time to waste. Rather than cowing to the Albanese government’s austerity agenda, unionists should take inspiration from the past and start rebuilding a radical working-class movement focused on achieving transformative change. The reformist agenda advocated by the RAFA coalition must be rejected in a favour of a more forthright extra-parliamentary Climate Jobs Guarante campaign capable not only of energising a new generation of activists, but also shifting the debate away from the current molasses of austerity politics and the “Jobs versus Climate” debate. Here, it is rank-and-file union members and grass-roots community activists — not Labor-aligned union officials or politicians — that must play the leading role.

[1] J. Lang 1961, “Menzies ‘ Gift to Communists”, Century, May 26 .

[2] ACTU 1961, “Decisions of the Australian Congress of Trade Unions”, September, 2001.0020, Box 147, Victorian Trades Hall Council Records, University of Melbourne Archives.