As Jumana Bayeh recently wrote in Overland, late February saw the unveiling of Universities Australia’s biggest summer secret: a new definition of antisemitism, ostensibly endorsed, without broader discussion and debate by all thirty-nine member universities. Bayeh’s literary approach — a forensic unpacking of the chaotic, unfocussed expression deployed by the drafters — foregrounds the subtexts underlying and animating the new definition. For example its equivocating style could allow for emancipatory calls such as “From the River to the Sea, Palestine will be Free” or students chanting “Free Palestine!” at campus rallies to be construed as antisemitism by those who will read this as a call to annihilate Israel.

What is occluded by this new definition — Bayeh argues —is a larger tapestry of state violence along with the publicly stated intentions of Israeli PM Netanyahu (against whom the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for war crimes) for a singular Israeli sovereignty over contested lands. How then does the definition, leaving broader regimes of violence outside of the frame, affect the possibility of defending Palestinian freedom and self-determination in the face of settler colonial state violence? And what does it mean that such a definition is drawn up from the context of one settler colonial society to defend the existence of another?

My interest in how the UA definition was arrived at comes from years of research on the role of law in settler colonial contexts. In particular, I have examined how a state with an illegitimate legal foundation like Australia attempts to hold questions of Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination at bay even when this foundation drives many of the seemingly intractable justice issues facing us.

As a teenager growing in working class Sydney, my decision to study law — and more specifically human rights law (as if I knew what that was!) — came from my lived experiences of racism, having been a child of migrants growing up “wog” in the “multicultural” ’80s. My anti-racism grew into anti-colonialism as I went from undergraduate law and literature degrees and then onto a PhD in cultural studies. Through this work I came to understand that being migrant settlers made us subject to racism but also agents of it since we were living, studying, building lives on stolen Aboriginal Lands. Once I understood that our relationship to racism was a structural power relation more than a set of personal opinions about others, I knew that living and working on stolen lands came with great responsibility.

My belonging in Australia, like the belonging of all non-Indigenous peoples, makes us a part of the workings of the colonial debtscape. All of us sustained by Aboriginal Land without being Indigenous to it are responsible for our part of the deep sovereign debt owed to Indigenous peoples on their lands. Instead of these debts of colonialism being acknowledged, they continue to be disavowed, buried and amplified by legal structures that form the carceral state.

Far from restoring justice, the colonial regime enacts its punishment logic to reaffirm its illegitimate presence. As Tony Birch has argued, before sovereignty can become even a viable concept for discussion amongst the wider non-Indigenous community, it needs to redeem and take responsibility for its colonial debts. It is against this backdrop that I offer some reflections on a few aspects of the recent UA definition of antisemitism — a definition that was drawn up on unceded lands that are impacted daily by deep structural and colonising racism.

Slucki and Gelber recently argued that it is no small feat that thirty-nine universities across Australia reached consensus on a working definition of antisemitism. Unlike Bayeh’s analysis, their article seeks to reassure those of us concerned that the definition will negatively impact academic freedom, arguing that instead it will generate conditions for staff and students to engage in debate over the war in Gaza in ways that do not harm others.

While the authors are correct that harm should not be done in academic debate about Gaza, where does their framing of this issue place the material and lived harm perpetrated in and against Gaza? This is a genuine question. Is it possible that in such a framing those debating /protesting are imagined as one distinct group while “others” are those who are considered capable of being harmed?

At any rate, there are at least two discussions of harm that are immediately relevant: that of material harm and violence in the war in Gaza and the harms that are possible in discursive responses to that war. An acknowledgement of the layered nature of structural harms present and possible within the context of the Gaza war is strikingly absent in the UA definition. This omission is far from reassuring for those who understand the structural harms of war as the central concern around which everything else should pivot.

The new UA definition of antisemitism moves us closer to the possibility that scholarly work calling for the elimination of settler colonial states could be deemed antisemitic. This should be of concern to scholars working on the theory and praxis of anti-racism, anti-colonialism and decolonisation. The definition stipulates that

criticism of the policies and practices of the Israeli government or state is not in and of itself antisemitic. However, criticism of Israel can be antisemitic when it is grounded in harmful tropes, stereotypes or assumptions and when it calls for the elimination of the State of Israel or all Jews or when it holds Jewish individuals or communities responsible for Israel’s actions.

Leaving aside for now the question of who will decide on what constitutes harmful tropes, stereotypes and assumptions in university contexts, it will be important to monitor how the definition relates to existing scholarly literature across fields of knowledge that questions the existence not of peoples’ right to exist, but of the extractive and usurpatory settler colonial states themselves.

For example, Patrick Wolfe’s work — critical to the formation of the field of settler colonial studies — sets out how settler colonial states like Australia and Israel are inherently eliminatory and states that destroy to replace since territoriality is settler colonialisms specific irreducible element. Like this foundational conceptual work in the field of settler colonial studies, the UA definition has also moved to deploy the concept of elimination but does so by stripping it of its function in the Israeli colonising project. How will decolonising approaches to various disciplines fare in this academic climate given that decolonisation requires an undoing of colonial logics and state formations and cannot simply be a metaphor or stand in for change?

In fact, decolonisation demands self-determination for all Indigenous peoples, including Palestinian peoples upon their traditional lands. The UA definition asserts that “all peoples, including Jews, have the right to self-determination” but also remains silent on the specific question of self-determination for Indigenous peoples within this colony where military power and colonial violence are the foundations of the colonising project called Australia — an ongoing project whose incalculable colonial debt remains unpaid.

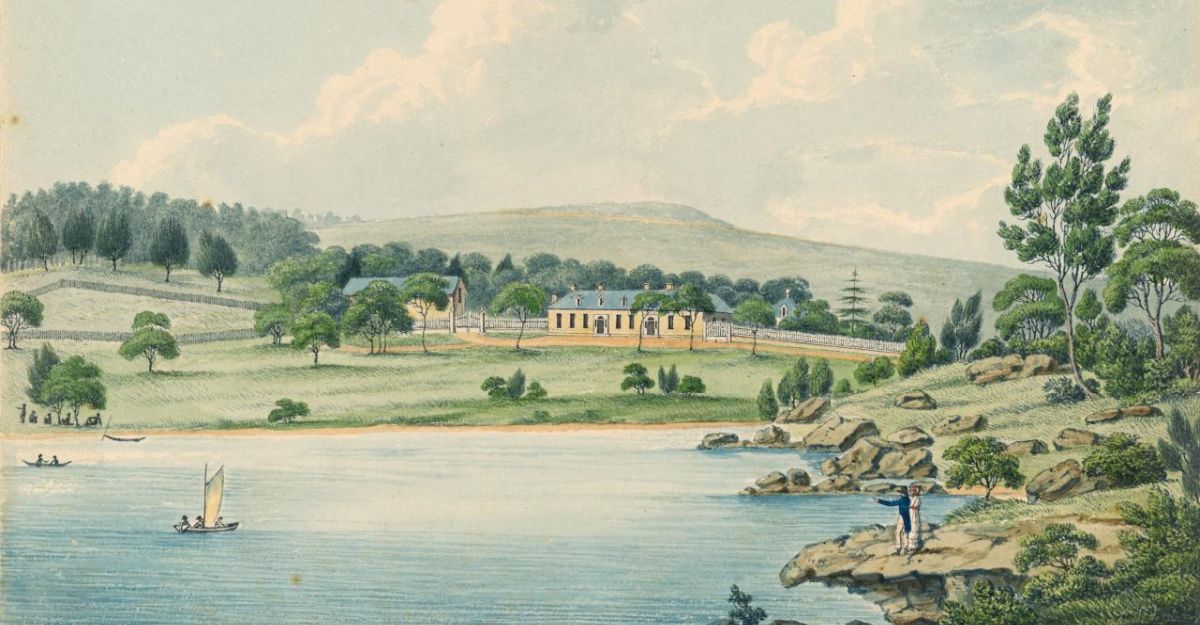

Image: Joseph Lycett, The residence of Edward Riley Esqr Wooloomooloo near Sydney, New South Wales (detail)