On the top floor of the ANA Grand Harbour Hotel overlooking Circular Quay, Japanese fine-dining restaurant Unkai serves kaiseki ryori, featuring some of the best seafood Sydney has to offer. As the ferries below chug back and forth, the chefs quietly prepare sashimi while guests soak in the harbour view.

Conceptualised during the peak of Japanese economic dominance, the hotel opened into a very different world than the one it had been built in. With the onset of the Lost Decades, it struggled on just past the new millennium, before being sold and renamed in 2003. Along with it, Unkai closed down and its once prestigious name fell into obscurity.

The food industry is notoriously one of the hardest places for businesses to survive, even when times are good. While food is a central part of cultural expression, it faces the risk of lifelong debts, constant anxiety and professional burnout — all just to stay afloat. Furthermore, exploitation runs rampant. High-profile cases such as the wage theft scandal involving former MasterChef judge George Calombaris highlight the abusive conditions that undergird our entire political-economic landscape.

Nowadays — twenty-some years after the close of Unkai — Japanese food is a major player in the dining scene of every Australian city, covering a wide range of styles. No longer exclusively the domain of Japanese chefs with deep roots in traditional culinary practices, the new mix of casual dining and simple sweet shops reflect the ever-changing construct of Japan within the imagination of the West. Just as Japanese food is being consumed by people all over the world, so, too, is it increasingly being prepared by non-Japanese hands. Within Sydney, “traditional” Japanese restaurants like Unkai have given way to the likes of Uncle Tetsu’s, Tokyo Taco and Dopa by Devon, eateries that have adapted to the idiosyncrasies of the city’s foodie culture. As these newer restaurants stray further from the cuisine’s origins, questions have arisen about the nature of its authenticity. Do these newer restaurants constitute real Japanese cuisine?

From the late noughties onwards, something clearly changed in the character of Japanese cuisine. Once quarantined to the exclusive world of fine dining, it has now exploded — saturating every pore of the CBD. The most vivid manifestation of this phenomenon is the rise of the ramen shop. A darling of both Japanese corporations and “plucky” Australian up-starters, this is the trend that everyone seems to be getting in on. No-nonsense chains operate alongside “Michelin starred” $50 ramen restaurants, a far cry from its origins as a cheap and simple dish for the masses. Indeed, ramen’s evolution within Sydney echoes the trajectory of its development in Japan, and beyond. What was once a working-class meal is becoming more and more expensive.

Part I: Ramen review

Japan and ramen

Japan’s status as an object of Western fascination has a long history. Dating all the way back to the 1800s, our story begins with the first arrival of Perry’s black ships, marking the end of the Sakoku Period. The Japonisme trend saw a frenzied export of Japanese design aesthetics overseas. European artists received these ideas with great enthusiasm, influencing movements like Art Nouveau, which incorporated these new-found design sensibilities, as exemplified by The Peacock Room. Here the large murals of peacocks take inspiration from Japanese lacquerware design, using gold leaf that stands in stark contrast to the dark black-blue background, while the patterning and style are very evocative of ukiyo-e artworks. The centrepiece portrait, The Princess from the Land of Porcelain (1865), itself is an example of Anglo-Japanese art, with the figure wearing a kimono and holding an uchiwa fan in front of a folding screen. The craze carried into Art Deco, with black and gold motifs as well as gingko-leaf inspired patterns. The geometric, rectangular designs prevalent in many Art Deco pieces can also trace influences from Japanese interior furniture.

At the same time as Japanese cultural products were being exported, Western technology and ideologies were imported, rapidly modernising both the military and society. With the dawn of the Meiji Restoration, Japan transformed itself into a dominant power in Asia, quickly establishing its own colonies. Whilst still exhibiting supremacist and patronising views towards its Asian subjects, the country opened its ports to an influx of migrants. In the revealing book The Untold History of Ramen, George Solt chronicles the process by which a significant Chinese labour population came to form near the port of Yokohama, introducing one of the precursors to ramen to Japan.

Lā mien, popularly known in Japan under various names such as Shina-soba, Nankin-soba or Ūshin-udon, was considered a small, simple dish served at the end of a meal rather than a whole meal by itself. Initially, Chinese migrants were the main consumers of Nankin-Soba, however it soon spread and quickly became popular with the Japanese working class, particularly among factory workers due to its hasty turnaround and low price. As most of the components could be batch-prepared beforehand, only needing a few minutes for the noodles to be boiled, ramen could be quickly served and eaten. Furthermore, the fatty oils and meats provided a potent source of energy that sustained workers during the long and gruelling shifts at the factory. Thus, Shina-soba became a symbol of industrialising and modernising Japan.

However, this rapid modernisation — fuelled and sustained by its emulation of European colonial campaigns — threatened Western hegemonic interests in the region. This led to Japan being beset with economic sanctions aggressively designed to cripple its economy. Confronting economic collapse and European subjugation — a fate similar to China’s after the Opium Wars — the Japanese state pushed further and further into an imperial-military dictatorship. The expansion of its colonial interests secured new resources that kept its economy afloat, culminating in the annexing of Manchuria and Japan’s entry into the Second World War.

In his comprehensive book on the history of ramen, Slurp!, Barak Kushner details how government intervention shaped the evolution of the dish. To aid in the war effort, Japanese authorities outlawed food vending, as well as introducing a food rationing system. Nationalist propaganda, from both grassroots middle-class movements and the state, turned food into a symbolic display of patriotism, captured in the phrase “Kokuminshoku,” meaning something akin to “the people’s national food.” Rice thus became the centrepiece of the Japanese diet. This focus partly served as a way of easing the population into accepting food restrictions. Once an unattainable luxury for common people, rice — particularly white rice — was added into the ration mix by the state as a sort of compromise. The proliferation of rice and the xenophobic attacks against Chinese culture, now a colonial subject, led to the disappearance of ramen from Japan during the War period.

The “economic miracle” that followed Japan’s defeat in WWII echoed its meteoric rise to power during the Meiji Restoration. As rice imports from its colonies ceased, Japan’s food shortage acutely worsened after its surrender. In response to these conditions, the occupying Allied forces imported American wheat as aid. As documented in The Untold history of Ramen, diverted government supplies and bartered American rations were the cornerstone of the black markets that flourished immediately after the war, selling the flour at a steep markup even though wheat was not a staple in Japanese diets at the time. Ramen stalls returned to the streets of Japan, closely following the flour trail left by the black markets. It was seen as a socially acceptable use of the American occupier’s aid rations, over other foods like bread — a symbolically Western product. With the return of Canada and Australia’s productive capacity, however, global wheat prices dramatically fell. Japan and other Asian countries consequently became an absorber of this mass surplus in wheat, and ramen quickly returned to its pre-war status as the food of the working class, fuelling the historic task of (re)building the nation.

The invention and mass-scale production of instant ramen allowed by the abundance of wheat flour further catapulted ramen to its status as a staple of Japanese cuisine. Instant ramen, starting with what would later become Baby-Star Ramen, entered the Japanese market in the mid-late 1950s. Chikin Ramen by Nissin Foods was an instant hit, quickly spreading throughout Japanese society and becoming a symbol of mass-consumerism.

Starting in the 1980s, at the peak of Japan’s economic dominance, the “gourmet boom” saw a renewed interest in food as a response to Warhol-esque mass-culture. Mirroring today’s obsession with authenticity, the Gourmet Boom “rejected” instant ramen for the boutique, fetishising intricate knowledge of food as a form of cultural capital. According to both Solt and Kushner, the Japanese government capitalised on this trend and integrated the Gourmet Boom as a core part of its strategy to revitalise the rural economy. By travelling across the country to try out all the different regional specialties, young, trendy, middle-class consumers propped up local economies through tourism.

From the warm miso ramen topped with butter and corn perfect for the cold winters of Sapporo, to the pitch-black soy sauce soups of Toyama, ramen was the means through which a region could highlight their unique qualities. Concurrently, the popular fantasy of opening a ramen shop took hold as a reaction to the monotonous and alienating routine of being an office worker. Through a combination of these trends, the ramen shop came to symbolise stubbornness, freedom, and dedication to craft. Paradoxically however, the Gourmet Boom was also the catalyst for a new wave of soon-to-be ubiquitous ramen chains: Korakuen, Ippudo and Ichiran all started their franchising journeys during this period. Encapsulated in the statement that Ippudo aims to be “the Starbucks of ramen,” the rise of the ramen chain represents the pivotal subsumption of ramen restaurants into mass-consumerism.

With an eye to expanding abroad, Nissin released a cupped version of instant ramen which could be eaten with nothing but a fork. With this innovation, instant noodles found their way into American culture, quickly becoming the champion of the frugal college student. Ramen shops would soon follow. However, just as in Japan, prospective restaurants would now need to market themselves as offering a premium product — something worth the extra cost and time.

The story of ramen in Australia

Japanese restaurants used to be a rarity in Australia. Only a handful existed in the 1980s, catering almost exclusively luxury fine dining. Though a result of the White Australia policy, Japan’s aggressive imperial expansion South into Asia was cited as a key reason for the restriction of Asian immigration. The end of the policy in 1973 saw the non-white population increase greatly. With Japan’s reputation successfully “rehabilitated”, Japanese corporations and people slowly began to migrate to Australia — peaking in the 1980s during the heights of Japan’s economic success. The Lost Decades precipitated a trend towards younger migrants, a demographic shift which manifested most visibly in a new influx of Japanese restaurants. As NSW has always been the most common destination for Japanese immigrants, Sydney became the entry point for Japanese cuisine in Australia.

For a long time, Ichiban Boshi — opened in 1998, just a few years before Unkai would close — was one of the only ramen restaurants in Sydney. Located within a two-storey rowhouse-style building, the original flagship store in Bondi was fairly unassuming. No particular emphasis was placed on its Japanese heritage, save for the noren curtain placed in front of the door. As a child, I remember eating here with my family, as they were by far the best in Sydney. The ceiling fan on the second-floor span wildly in the summer heat, distracting me until my chashu ramen arrived. Offering a wide range of ramens, from Tokyo-style soy to Sapporo miso and salt soups, Ichiban demonstrates how varied ramen can be. Their lighter broth allows for the toppings to be emphasised, with the chashu (braised pork) being the standout. The gyoza, with a dab of gochujang swimming in a pool of vinegar and soy sauce, gives a refreshing, tangy change of pace. Ichiban stands out as one of the few ramen restaurants in Sydney that primarily uses chicken stock as the base for their soups. While Ichiban Boshi was seminal in establishing ramen within the city’s foodscape, it has been usurped – it is tonkotsu ramen that has conquered Sydney. With its rich and meaty flavour (its broth made from pork bone), this variety has found more popularity among Western palates compared to the country of its birth, where tastes tend towards lighter and refined flavours. It is no surprise then, that most of the newer ramen shops have specialised in tonkotsu ramen.

Tonkotsu takeover

Throughout the noughties and early 2010s, various ramen joints popped up and just as quickly closed.

Following the success of Ichiban, four brands came to represent key characteristics necessary for survival. Gumshara (opened in 2009) was one of the first ramen restaurants specialising in tonkotsu ramen to establish itself as a long-time player in Sydney. Having one of the thickest and strongest soups, it was completely polar to the subtle broth of Ichiban Boshi.

Already a large name within Japan for locals and tourists alike, Ippudo opened its first Australian store in 2011 and quickly expanded to twelve stores in 2024, with seven of them in Sydney alone. Ippudo’s menu centres around their two specialty ramens. Originating in Kyushu, the Shiromaru Classic is Ippudo’s version of their original Hakata-style ramen. The rich, meaty flavour of tonkotsu reflects Kyushu’s history as home to one of the few freeports during the Sakoku period. Barak Kushner has explained how cultural cross-pollination between locals and foreign merchants resulted in the people of Kysuhu becoming more comfortable with eating meat compared to the rest of Japan, where meat consumption was much rarer at the time. Hakata ramen differentiates itself from other tonkotsu ramens by its crisp noodles that complement the heavy soup, as well as the kikurage (black fungus) topping. The Akamaru Modern alters the classic flavour by adding some spicy miso, creating a new dimension on top of the meatiness. By aggressively expanding globally as well as within Australia, the franchise has further solidified ramen as an institution not just within Japanese cuisine, but also in our dining scene. Ippudo’s first store in Sydney Westfield delivered a gourmet dining experience — the décor and atmosphere deliberately evocative of Japanese cuisine’s fine dining history. Their second store in Central Park pared things down with a more casual atmosphere, reflecting the large student population wandering around TAFE, UTS and the University of Sydney.

Chaco Ramen’s (2014) casual dining experience contrasts with the refined focus of Ippudo. Innovating the “Ramen bar”, Chaco incorporates elements of the izakaya, bringing a social element to ramen and catering to the young trendy crowd around Darlinghurst. According to Iori Hamada in her insightful book The Japanese Restaurant, the izakaya was introduced to Australia in the early 2000s, attempting to introduce casual Japanese dining to Australia by presenting it as a Japanese twist on Spanish tapas and local pub culture. Their Fat Soy is another Hakata-style ramen, ever so slightly heavier than Ippudo. Other ramens on their menu, such as the Yuzu Scallop, bring a modern slant. What makes Chaco stand out is their extensive drinks menu. From house-made liqueurs to Japanese beers, sake and shochu, Chaco invites you to enjoy your stay in their cozy store. The small dining area is enclosed within grey concrete-like walls, decorated with wooden plaques inscribed with typical menu items of an izakaya (in Japanese of course). Colourful rope flags accompany the dim lights hanging from the ceiling. Every inch of space is utilised, with drinks, cups and menus, crammed and stacked onto any flat surface available, giving off a palpably homy atmosphere. Chaco pioneers a new dining style, one specifically tailored to Sydney’s culture and climate.

Finally, Yasaka Ramen is exemplary of how ramen restaurants not only heavily use social media for marketing, but also emphasise their ties to Japan and lean into Hamada’s concept of the “New Exotic”. Their posts on Instagram and Facebook constantly allude to their Japanese roots, highlighting how Yasaka import “specialist equipment”, even charcoal, from Japan, or that the design of their ground floor counter is “very much inspired by the Japanese noodle houses.” One post describes takoyaki as “traditional food,” even though its origins are not even a century old. Whether it’s the neon-lit interior décor, the noodle rolling machine at the front, or their motto, “No Ramen, No Life” (a phrase template originating in Japan), there is a concerted effort to catch people’s attention with theatrics. Heavy profiling of co-owner and head chef, Takeshi Sekigawa (who previously worked at Gumshara), underlines this new effort to highlight its Japanese heritage, especially compared to older ramen restaurants (like Ichiban). It also hides the fact that the ramen at Yasaka is not particularly good. It has an almost muddy consistency, the soup clinging to the noodles. The broth attacks you with full force, having extracted every last bit of flavour from the bone and marrow.

These four restaurants — Gumshara, Ippudo, Chaco and Yasaka — encompass key traits that contribute to the success of the next two restaurants to be discussed. To stand out in this newly saturated market, Rara Ramen and Ramen Auru take these isolated traits and mix them together to entirely new effect. These two restaurants mark the shift towards an overriding emphasis on authenticity. Together, they exemplify the “Ramen Authentic”.

Rara Ramen

Established in 2018, Rara Ramen in Redfern is one of the newest ramen joints on the block. After a fateful holiday to Japan in 2011 where they fell “in love with ramen”, owners Katie Shortland and Scott Gault returned with the novel idea of opening a ramen restaurant in Sydney.

Rara is situated inside a converted historic two-storey brick building. The bottom floor of the street front has been hollowed out and replaced with a contemporary large glass window, and the entrance has moved to the side of the building, facing the neighbouring Iglu student housing complex. Inside, the décor takes a much more modernist style, alluding to the urban streets of Tokyo. The harsh corners of the concrete counters and walls as well as the black metallic stools give off a cold atmosphere. Architects like Takao Ando and buildings like the Nakagin tower come to mind. Faces are lit by neon signs dotted throughout the store, with dim down lights providing a dome of light for the mandatory Instagram photo. The bar sits front and centre, where a row of Japanese drinks are proudly displayed, lit by a strip of LED lights beneath the exposed faux-truss brackets. Unfinished wood grain is another prominent background motif. While contrasting the cold brutality of concrete, the “natural” character of the wood is undercut by the industrial crudeness displayed in the grain finish. Outside seating is offered on misbalanced wooden stools and “makeshift2 wooden tables, almost reminiscent of the minimalist design senses of Muji.

The minimalism continues in the menu, bowls and food. The base ramen, RaRa Tonkotsu, is uncannily similar to Chaco Ramen’s Fat Soy in flavour (though not necessarily in quality). Options to add chilli or black garlic don’t amount to much, especially for an extra $2. The sides aren’t amazing either, their gyoza completely forgettable. Much like Chaco, the extensive drinks menu highlights the focus on the ramen bar experience. A range of Japanese beers, both on tap and bottled, accompany a few craft beers and wines from cask. Brand name Japanese liquors — Suntory Toki and Roku, Choya plum wine, -196 chuhai and a few sake options take up space on the bar counter. Even the non-alcoholic drinks are largely Japanese, with drinks like Calpis, Pocari Sweat and Ramune.

Like Ippudo, Rara has aggressively expanded its franchise. Opening in 2020, their second store in Randwick marked Rara’s focus on Sydney’s suburbs. The affinity between Shortland and Gault’s background as members of the professional-managerial class and Randwick’s own largely professional residents points to the likely rationale of an otherwise seemingly odd location choice. By situating themselves in the re-developed Newmarket complex, the owners aim to capitalise on Randwick’s key position as the “gateway to the East[ern suburbs]”. Their short-lived experiment in Newtown, Lonely Mouth, specialised in vegan ramen and dropped the cyberpunk aesthetic for a more naturalistic atmosphere using bamboo curtains and washi paper-like lamps. Following this, Rara chan in Eveleigh (now closed) doubled down on the concrete-jungle vibe. Aspiring to be resemble much closely a traditional ramen store, it fits seamlessly into the vapid business park, where office workers can quickly eat their ramen during their lunch break. Rara’s latest Gold Coast joint faired no better, closing as quickly and quietly as it opened.

Every decision Rara has made about their stores is a deliberate choice to create the air of authenticity, highlighting the restaurant’s Japanese-ness. Architecturally, all their locations desperately borrow from aesthetic elements associated with Japan — whether it’s the minimalist and industrial concrete counters, or the unfurnished woodgrain detailing, or the neon-style lights. Of course, the ramen is also infused with “authenticity”. As guardians of a “top-secret recipe passed down from a mysterious compendium of ramen masters in Japan”, Rara flirts with oriental mysticism. Similarly, their centrepiece neon sign at the Randwick store reads “Big Noodle Energy”. Just as a “spice” can be imbued with orientalist tropes, “noodle” hints at some form of exoticisation.

This underpins the sense of unease I feel at many of the ramen restaurants in Sydney. It’s a sensation further contextualised by Ghassan Hage’s concept of cosmo-multiculturalism, where he postulates that, in Australia, multiculturalism is centred on a “white nation fantasy.” As Iori Hamada further outlines:

Multiculturalism as ‘cultural diversity’ uses non-white ethnicities as a way of valorising a white centre, while at the same time superficially valuing ‘cultural diversity’ where non-white ethnic subjects are involved. … Australia’s form of multiculturalism centres on reinforcing whiteness, not other ethnicities, whereby white Australians can experience ‘cultural diversity’ as part of their own ‘cultural enrichment’.

Thus, the bubble of authenticity is burst. And all the little elements start to jump out as wrong. While brutalist buildings may be abundant in Japan, interiors are typically much more warm and lived-in. The clash between the patronage style of the quick-stop ramen shop and the lounging izakaya becomes especially jarring. Conspicuously clean neon-like LED signs emanate a thin, cold light. They attempt to evoke the grimy back alleys of Tokyo, yet this superficiality emphasises the failure to replicate the stuffy warmth of cramped dive bars. Only serving the “cool” and pricey Japanese liquors again highlights the departure from the izakaya’s role within Japanese society as a space for communal bonding over cheap drinks and shared plates.

Key elements of Japanese cuisine are locality and domesticity. Regional specialties create a sense of uniqueness, and therefore scarcity, creating the impetus to travel to the actual place. Orion beer, a brand so heavily associated with Okinawa, is oddly placed in a generalised ramen store. Equally, and ironically, Western liquors like Jim Beam that are a staple at many izakayas in Japan are conspicuously absent here, emphasising the concerted effort in decorating Rara with a pastiche of unreal Japanese aesthetics. It seems that Rara painstakingly imported the “Suntory Whisky” Jokki mug, with its iconic yellow label. Yet, they opted to use Toki rather than the cheaper Kaku whisky, which the yellow label is supposed to match.

At every stage of the design process, the owners of Rara have gone out of their way to evoke Japan. Yet each choice adds to a larger sum that speaks of its artificiality. It highlights the owners’ cosmopolitan background, clothing themselves in a culture that isn’t their own.

Ramen Auru

On a cold Wednesday evening in May, I made my way to Crows Nest after a long day of work. Packed into the backseat of the 320, I scrolled through Ramen Auru’s buzzing Instagram page. All the posts talked about how Japanese it felt, about the ticket vending machine — it even had tatami seating!

I arrived and met my friend outside what seemed to be a non-descript building: a grey two-storey townhouse, with a small door entrance on the left side. As I turned into the doorway, was greeted by a line — maybe twenty people deep — hugged to the left side of a narrow stairway. A wooden door to the right of me slid open and a group spilled out of another restaurant on the ground floor. As the line ahead of me crawled forward at a snail’s pace, I took in the details of the entrance hall’s decor — only lit by the thin red light emanating from the overhanging paper lanterns and the cube-shaped way marker outlining the floorplan (Yakitori Yurippi on Level 1, Ichiro’s Bar on Level 3, and Ramen Auru on Level 2).

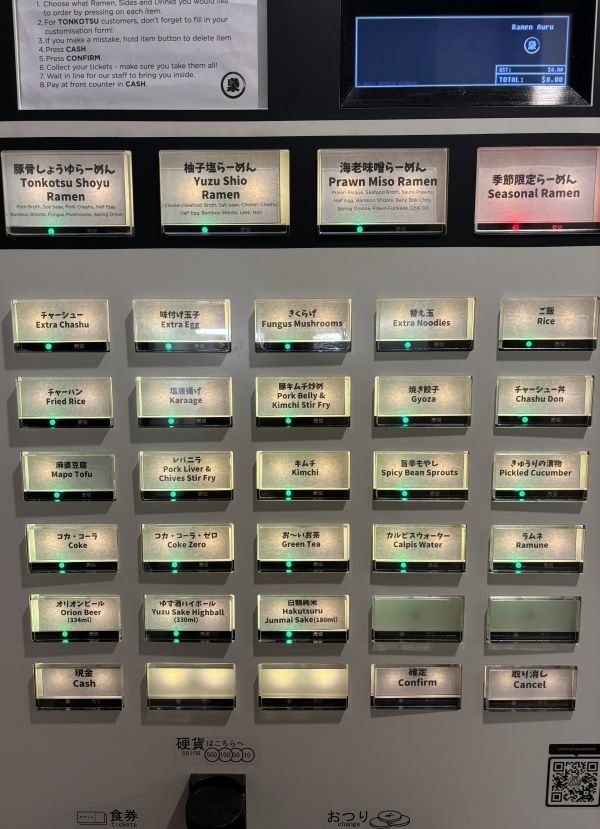

Thirty minutes passed, and finally we reached the front of the queue, where the large ticket vending machine loomed in front of us. The attendant politely asked us to order our food. As I had already seen all the hype around this newly opened shop, I knew how to navigate the messy machine — not everyone did! Once we got our tickets, we were directed towards the counter at the front to pay. The cashier took our tickets and pointed to our table, slightly disappointed that we didn’t get to sit on the tatami or even the counter.

Once inside, the atmosphere was surprisingly very much of a typical ramen shop in Japan. The blank walls were covered in stucco, resembling Japanese shikkui, only broken up by dark-brown wooden columns. The chatter of patrons was drowned out by the cacophony of clattering pans from the open kitchen as well as an eclectic mix of Japanese pop from various eras and Okinawan folk music. Seated by the window, we looked out to see another three Japanese restaurants on the other side of the street as we waited for our food to arrive.

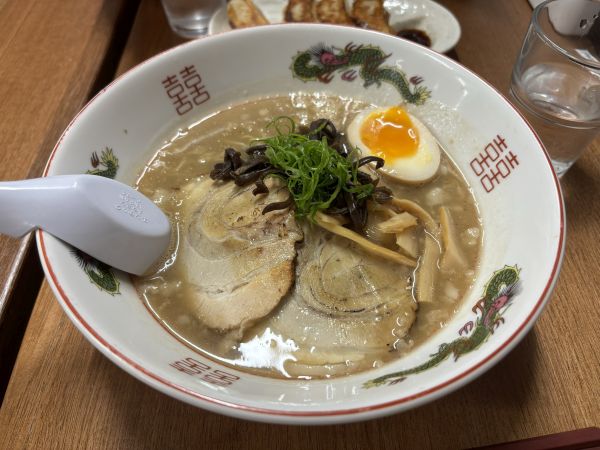

The gyoza arrived first. The golden-brown undersides still had some of the burnt straggly bits hanging on. The flavours weren’t particularly complex, with nothing standing out. Common dishes like mapō tofu, fried rice, and chashu-don rounded out the sides. The ramen followed soon after. Currently, there are only three options: Tonkotsu, Yuzu Shio (salt), and Prawn Miso. I chose the tonkotsu. On the order customisation sheet, I circled the “hard” option for my noodles. Topped with all the regulars, the only difference was the very light sear (aburi) on the chashu. The soup was thick, bolstered by the heavy, muddy taste — a better version of Yasaka’s recipe. At any rate, it wasn’t my favourite. The chashu was thin and dry, almost tasteless, save for a hint of char. The only part of the dish that stood out was the menma (pickled bamboo). Self-serve water and barley tea served as something of a respite to the oppressive flavour of the soup. Coke was the exception to an otherwise entirely Japanese drinks menu, including green tea, ramune, Orion draft beer, and sake. I promptly finished my ramen before depositing my tray to the return bin and readied myself for the cold journey home.

*

Right from the very first step into their building, Ramen Auru felt as if it were a purposefully constructed space, maximally designed to transport you to a foreign land — the way-marker cubes in front of the narrow and steep staircase felt uncannily Japanese. The ticket machine hovers over you as you turn right up the stairs. Although the venue is currently cash only, it doesn’t go in the machine. A fake coin slot and change chute further confuse guests, who are then directed to pay at a separate counter — quite emblematic of the whole experience.

The effort the staff went to keep up the charade was very apparent to bystanders. The attendant clung by us to ensure a smooth ‘experience’. Time and time again, staff had to step in as people were confused by the convoluted ordering process. While the ramen options are helpfully differentiated with big buttons at the top, the rest of the menu gets lost in the standardised plain text on white background (in both English and Japanese). Having the payment option in the same matrix only adds to the mess. The supposed reason for the ticket machine was for “efficiency and to eliminate confusion between the customer and the kitchen”. However, most other restaurants that use tablets, QR codes, or even staff physically taking orders don’t seem to have any problems. Instead, Auru adds extra steps, with two staff members required to deliver your order to the kitchen. Since the machine had to be custom built — “the only one of its kind” — it isn’t necessarily cheaper than purchasing a dozen or so tablets either.

As explained by Jorge Almazán in Emergent Tokyo, ticket vending machines are largely used at small eateries to reduce the number of staff on payroll. The small scale reduces the upfront and operational costs, lowering the economic barrier to entry. Like the bars in a yokocho, this allows for just one person to manage the whole place and have complete creative control. This harkens back to the escapist fantasies of salaried workers — their desire for the freedom to express themselves as they wish. Furthermore, the streamlining of the dining experience also helps keep ramen shops that rely on a distinctly high turnover of guests afloat. Ramen Auru’s 50+ occupancy venue seems contradictory to the original intent embedded in this design. The slower eating style and the large staff make apparent just how out of place the ticket machine is.

The tatami section caused yet more problems. If you were seated at a tatami table, the staff would call out your order number when ready and you would need to go collect your food from the edge of the tatami section yourself — as shoe-wearing staff could not enter. From the outset, a full seated tatami section seems rather contradictory to the fast-paced ramen style, which, for a store that prides itself on emulating Japan as much as possible, is an odd detail to miss. The return bin was rarely used by guests, further requiring a staff member to vigilantly patrol the tatami area to make sure the tables were cleared and cleaned before patrons put their shoes on.

Auru — a Japanese pronunciation of the word “owl” — has another piece of ramen lore in mind. With last order at 11pm, it attempts to bring the routine of ramen as a shime (closing dish) for a long night out drinking to Australia. However, this detail is buried even in their puff-piece in Broadsheet. The restaurant’s Instagram heavily focuses on Australia/Sydney’s “first ramen ticket vending machine” and the tatami seating. While the showpiece of the vending machine draws the crowd in, the subtle décor papers over the superficiality of manufactured authenticity. Supposedly, Ramen Auru is not just “about TikTok-baiting gimmicks”, but about constructing an experience.

So, how were Auru able to afford such extravagant displays of Japan? This requires a deeper dive into Hatena Group, the owners of Ramen Auru. Co-founders Tin Jung Shea and Mitomo Somehara, started their journey in 2015, opening Yakitori Yurippi in Crows Nest. As with the the origins of Yasaka Ramen, Chris Wu — previously a regular customer at Yurippi — joined the duo to set up the Hatena group. Quickly expanding to five restaurants dotted throughout Sydney, Hatena group has established themselves as a major player within the Japanese dining scene. Besides the rather random name (Hatena means “question mark”), the clean website is heavily laden with corporate buzzwords and fluff, queasily reminiscent of Silicon Valley tech-bros.

What Hatena have actually done is successfully commodify culture at scale. What differentiates a restaurant like Auru from, say Rara, seems to be their connection to the Japanese community. The heavy involvement of Japanese people in Auru results in an overall more cohesive and “believable” emulation of Japan. Auru seems to heavily recruit Japanese staff, most likely vacationers on Working Holiday Visas, hinting at their connection to the Australian-Japanese community at large. Japanese-language jobs boards have a gatekeeping effect, funnelling Japanese backpackers towards establishments managed by Japanese people. Hatena’s scale also results in interchangeability within their ecosystem, allowing staff from one restaurant to move to another easily if needed.

Scale also allows for a pooled income, creating a drastically larger inflow of revenue to draw on, enabling more ambitious projects. The diverse range of dining styles caters to a wide variety of guests — from a laidback social atmosphere at izakaya-like Nakano to the more upscale experience of Indigo’s sake tasting bar. Their most ambitious project yet, the Crows Nest complex, stacks three of their restaurants for a complete dining experience.

Starting with a few bites at Yakitori Yurippi, you can then go to Ichiro’s Bar for some drinks and sport, then finish the night off with a bowl of ramen at Auru. The small footprint of the building, narrow stairways, non-descript signage, are a constructed copy of the Yokocho alleyways and Zakkyo buildings of Japan. Architecture firm, Studio Hiyaku, named after “the Japanese concept of “Hiyaku” or “Leap”” — which appears to me to just be a random Japanese word chosen for its aesthetic appeal — were commissioned to work on the interior designs of the Crows Nest complex. The lack of apparent connection to Japan or Japanese culture perhaps explains the logic behind having a large tatami section inside a ramen shop. It would have made more sense to have tatami seating within Yakitori Yurrippi, or even Ichiro’s Bar — restaurants suited for a slower eating style — which they were also commissioned to design.

Packing three eateries into the space of what was previously just one, the owners may have succeeded in crowding out their competition. What would have otherwise been a journey through different venues, has become one, charging patrons three times for three “separate” events. The yokocho experience is thoroughly commodified for the Australian patron, but eating at any of these venue means to experience a degree of objectification. At Nomidokoro Indigo, another Hatena property, a Japanese Washlet (an electronic bidet-toilet, ubiquitous in Japan) has been imported and subsequently incorporated into bartender-customer chatter. Patrons, enamoured by such “small details”, leave very much satisfied. They have just had an “authentic” Japanese experience, right in their backyard! As one of the patrons at Ramen Auru exclaimed as they walked out while I was waiting in line — “I feel like we’ve just been in Japan!”

Part II: Why so authentic?

Gatekeeping authenticity

Authenticity is now a key criterion in judging the value of a restaurant. Particularly with ethnic cuisines, a restaurant’s proximity to its roots is strategically emphasised. However, we must ask the question — why has authenticity become so important to consumers and businesses alike?

Iori Hamada underlines the fact that Japan is seen as a “Westernised” Asia, “in, but above Asia,” a “non-Western and un-Asian entity,” conferring on it a unique status as a gateway between the familiar and the exotic. She explains this idea in an interview with the owner of an izakaya in Melbourne that introduced sake and Japanese drinking culture to Australians by relating it to Australian pub culture as well as share plates. These acclimation practices position Japanese cuisine as the New Exotic, a predictably unique experience rather than completely foreign. A foreign experience, without being alien. In this sense, Japanese cuisine can act as a bridge to other, more “intimidating” cultures, owing to how it overlaps with familiar Western dining habits.

Herein lies another foundational myth of cosmo-multiculturalism, that “ethnic foods [are] tastier [and] more authentic”. While seeming to elevate often marginalised communities, this ideation perpetuates ongoing class dynamics. Following Hage, cosmo-multicultural consumption pits the white consumers against the ethnic worker, who is forced to sell their culture for a living. Rather than a cultural exchange amongst equals, the consumer–consumed dynamic underpins the imbalance in socio-economic power. In an environment where the food industry is constantly undervalued and exploited, it echoes Stuart Hall’s famous insight about how race can be a modality through which class dynamics are experienced.

A new dynamic has recently emerged with the rise of an Asian middle-class who now have the means to capitalise on an untapped market: leveraging the perception that ethnic individuals have a unique access to culture, these visibly Asian influencers are creating popular “foodie” Instagram pages to act as “cultural tour guides”. These are further evidence of the shallow promises of such multicultural idealism — within a market dictated by the tastes of cosmopolitan consumers, each shop needs to push the boundary for the “most authentic” experience, distilling “culture” into its most easily consumable form. In this way, cosmo-multiculturalism enables, if not accelerates, the opportunistic hollowing out of culture for profit.

“Authenticity” may be pursued with many motives in mind, but the central reason it is so coveted is because it forms the basis for monopoly rent. As David Harvey explains in his recent book Rebel Cities, through exclusive control over an item that is “in some crucial respects unique … social actors can realise an enhanced income stream over an extended time.” In short, authenticity is a means by which scarcity is generated and subsequently controlled. However, tension arises from the competing forces of marketability and uniqueness.

Bringing products to mass-market successes allows for greater revenue. Yet, this scaling also leads to a homogenising effect, flattening its unique qualities, becoming less scarce. As a result, social institutions must be formed to reproduce the conditions that allow for scarcity and the ensuing monopoly rents to be sustained. For example, the Appellation d’Origine Contrǒlée (AOC) exists as a means to distinguish French cultural products. Strict rules and definitions are created and given a name, elevating Champagne and Comté from other fine wines and cheeses. The “unique” virtues of French terroir (land, climate and tradition) geographically lock the production of “premium” wines to a certain, limited plot of land. The AOC’s position as an expert authority gives it the unique ability to simultaneously produce scarcity — creating infinitesimal differences between wines — as well as make its exports more easily identifiable, trading on prestige name value.

Inspired by this innovation, the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) attempted to create a Japanese food licensing system in the mid 2000s. Derided as the “Sushi Police”, undercover inspectors would secretly inspect sushi restaurants abroad, then post on the official MAFF website a list of “approved” authentic Japanese restaurants. After a wave of backlash, the program was initially walked back to an opt-in certification system, before eventually evolving into a campaign of seminars, fairs and competitions aimed at disseminating the authentic method for preparing Japanese food. This turn also had the added aim of bolstering Japanese agri-food exports, placing emphasis on the use of Japanese products, such as rice and sake, as a necessity for quality Japanese cooking.

Reminiscent of “kokuminshoku” from the 1930s, the renewed focus on Japanese cuisine’s authenticity represents a notable outcropping of culinary nationalism. Indeed, the instigating factor for the Sushi Police was due to the fear of Korean, Chinese, or Filipino restaurateurs “pretending” to serve Japanese food. While there is an argument to be made that ethnic cuisines are best understood by members of that culture, the xenophobic undercurrents cannot be waved away. Whether it is the condescending derision within the word ジャパレス (read: japaresu, a portmanteau of Japanese restaurant), used to describe many Japanese restaurants abroad, or the disparaging remarks made about non-Japanese run restaurants, all of this reflects the history of Japan’s conflictual relation to other Asian countries.

Within Japan, ramen’s history has constantly been rewritten, erasing the significant contribution made by Chinese people. While many authors exalt ramen’s connection with the post-war black markets, highlighting its working-class appeal and saviour status, many rarely acknowledge Chinese involvement. As Solt’s research reveals, arrest records highlight an overwhelming Chinese presence in ramen vendors at the time, as well as implying uneven enforcement of food-vending laws. The labour of Chinese and Korean sellers was occluded from view. In their stead, Japanese colonial “returnees” were valorised as the working-class heroes that fed Japan during the dark days of the post-War period. Similarly, Japanese Barbecue’s (JBBQ) Korean roots have also been thinned and usurped, with many perceiving JBBQ to be a more premium product. Even one of the earliest pioneers of instant ramen disguised his Taiwanese heritage, a fact that may have precluded him from mass success. Japan’s wealth rests upon the labour of its former colonial subjects, its successes extracted from its imperial edges and paraded in the core. With a vast majority of Japanese restaurants globally run by non-Japanese people, Korean and Chinese restaurateurs have played one of the largest roles in spreading Japanese cuisine across the world.

Authenticity is a slippery concept to define and can take many forms. Ning Wang outlines a three-tier structure to understand how authenticity as a phenomenon has transformed over the recent decades. At its most basic, an “objective” analysis measures an experience’s distance from an “origin” point. Taken a step further, authenticity can be “constructed” by taking the constituent elements of the “original” to amplify the original elements and paper over the inadequacies deriving from the replica. However, as experiences stray further from its origin, the appeal gradually shifts from the replication of the original towards the individual emotions and sensations evoked during an experience.

The pursuit of cosmo-multiculturalism is in part driven by a desire to affirm the individual’s existential authenticity, for an experience “in which one is true to oneself, and acts as a counterdose to the loss of “true self” in public roles and public spheres.” In other words, through cosmopolitan consumption, individuals can create the identity of oneself as a cultured sage, distinguishing themselves from the masses tethered to the humdrum reality of corporate urban life. Existential authenticity offers an escape from the antagonistic competition in everyday life, creating an “alienation-smashing feeling,” as Tom Selwyn puts it in The Tourist Image. Wang further elaborates that this is achieved through nostalgic and romantic lenses which

idealise the ways of life in which people are supposed as freer, more innocent, more spontaneous, purer, and truer to themselves than usual (such ways of life are usually supposed to exist in the past or in childhood). People are nostalgic about these ways of life because they want to re- live them in the form of tourism at least temporally, empathically, and symbolically. It is also romantic because it accents the naturalness, sentiments, and feelings in response to the increasing self-constraints by reason and rationality in modernity.

Thus, the ramen restaurant becomes the perfect nucleation site for existential authenticity. Tapping into its exotic roots, people are able to temporarily travel to a foreign experience and develop a new sense of self. The ramen-izakaya provides a site for intimate social gatherings, bonding over the collectively energising experience of cosmo-multicultural consumption. Yet, while it may temporarily satisfy the craving, it does not provide a solution to the underlying yearning.

The market logic that drives this alienation is also present within the authenticity industry. Competition amongst Japanese cultural vendors continue to one-up each other, flanderising Japanese culture along the way. As can be seen in Rara Ramen and Ramen Auru, Japanese culture has devolved and been distilled into cheap gimmicks. Décor has been satirised to the point of unrecognisability. Concrete is plastered everywhere, while people slowly eat their ramen — a dish designed to be eaten quickly — and laugh over expensive Japanese liquor. A convoluted ticket purchasing system and tatami seating plan point to a cargo-cult ramen restaurant, apparently not cognisant of why these systems are used in Japan in the first place. Orientalism has reappeared, now in an updated form. While all the focus is on an “authentic experience” — a cultural exchange — the fundamental driving force has been marketability — the exchange value of culture.

When the Japanese economy finally ran out of steam in the early 1990s, the government was spurred into action yet again, entering what David Banks refers to in his book, The City Authentic, as “the thirst games”. Competing to attract outside capital into its region, the Japanese government created program after program in the hope of revitalising its economy. Rara Ramen, Ramen Auru — and as I will go into — the Cool Japan Fund and Abenomics, are all playing the same game, just on different scales. It is precisely through this process that every last part of the urban environment is commodified. This is how culture becomes a gimmick.

Political economy in Japan

Back in the 1950s, the Japanese economic miracle dazzled the world. The unveiling of the world’s first High Speed Rail system in conjunction with the 1964 Tokyo Olympics symbolised the progress of Japan’s economic recovery and rehabilitation. At the same time, Japan’s rapid growth startled and unnerved Western powers. The Shinkansen — a physical manifestation of Japan’s industrial and technological rise — sowed the seeds for Japan’s changing image once again, going from “economic miracle” to “economic animal” as Japanese brands came to be more ubiquitous within Western markets. This dominance was abruptly punctured however with the shock of the 1973 OPEC Oil Crisis. Japan’s previously roaring auto manufacturing industry — symbolised by the likes of Toyota and Nissan — was hit especially hard, causing a nationwide depression and catalysing a major sectoral shift. In the wake of soaring fuel prices, the less energy intensive industries of electronics and technology emerged as a new spearhead for a resurgent economy, represented by companies such as Sony, Nintendo, or Casio. Within Western pop-culture, the concrete jungles lit by neon signs with Japanese writing featured in the Cyberpunk genre reflected the West’s anxieties about Japan’s returning economic dominance.

The subsequent three decades of economic stagnation after the bursting of the asset bubble in the 1990s, known as the Lost Decades, eroded the image of Japan as the “economic animal”. Concurrently, like many other states in the Global North, the Japanese economy was deindustrialising, pivoting towards an Intellectual Property-based economy. As industrial production moved towards mainland Asia, Japan would need to reinvent itself and its history once again. The Japanese state played a leading role in this process, Solt stresses, transforming itself into a highly coveted “incubator of fashion and cultural trends.”

The Cool Japan campaign, modelled after “Cool Britannia,” was established in 2002 and aimed to promote Japan’s “Gross National Cool” as a means to reposition and reignite the economy through exports of cultural products, ranging from anime and pop music to technology and design. Cool Japan broadly had three objectives: attract Western Capital, launder Japan’s reputation overseas — especially with its former colonies — and bolster national pride domestically. The government quickly found that gastrodiplomacy would be a strong avenue to direct this campaign. Following similar projects like Global Thai, the Cool Japan Fund (CJF) was set up to incentivise Japanese firms to expand overseas. Ippudo was an early beneficiary, receiving US$6.7 million of financing from the CJF, which helps explain why it suddenly entered and aggressively expanded in Australia. Domestically, Cool Japan gave fuel for the nationalist narratives of the Liberal-Democratic government. As Japanese culture boomed overseas, the image of “them eating our food” became the basis for national pride. Leveraging this sentiment, combined with the recognition of Washoku (Japanese cuisine) as an intangible heritage product by UNESCO, the Japanese government positioned itself as the “protector” of culture and assumed control over the production of Japanese cultural products. Nationalist sentiment cloaked the state’s desire to transform culture into a commodity, a warped shell of itself that could be packaged and exported overseas.

On the strength of Abenomics, Shinzo Abe was re-elected to parliament in 2012. Similar to Tanaka Kakuei’s rural revitalisation plan that laid the groundwork for the Gourmet Boom, the Abe administration aimed to revitalise the economy through public investment into private firms and tourism. The “Three arrows” of stimulative monetary policy, expansionary fiscal planning and targeted structural reforms were key in triggering an influx of Big Capital as well as tourists. Central bank driven currency intervention weakened the Yen, making it cheaper for tourists to visit Japan. The government invested domestically to attract tourists. Finally, structural reforms in the visa system changed the demographic of tourists entering Japan. Tourism numbers skyrocketed from the mid-2010s, going from 8.4 million annual travellers to 31.2 million in 2018 and sparking backlash from local communities concerned about overtourism, echoing objections from other popular tourist destinations, like Venice. The dialectic between nationalist propaganda musing on the virtues of Japanese culture and the pure commodification of its cultural products is all too clear: the tourism business is booming, all while locals struggle to find a seat on the bus, and narrow streets get overcrowded and polluted with garbage. Old establishments are displaced by tourist traps, further eroding the pre-existent local community.

The number of Australians visiting Japan also rose to almost half a million a year in 2019. Prior to 2012, Australian tourism to Japan was largely gatekept by the exorbitant costs of international travel, and thus mostly enjoyed by the wealthy. While still popular today, a major destination for vacationers were Japan’s powdery ski resorts, exemplifying the class characteristics of early travellers. This fact also reflects the general character of Sydney’s Japanese restaurants in this period. Most Japanese restaurants were restricted to the two ends of the spectrum —being either a small local mom-and-pop store run by Japanese immigrants, or a 100+ seat fine dining restaurant in the city. However, as travel to Japan was made more accessible and attractive to a wider range of people, such as Rara’s Shortland and Gault, the Japanese dining scene changed to reflect this. More casual and mass-oriented forms of Japanese cuisine have come to dominate the scene in recent years. The specific class composition of Japanese migrants coming to Australia as well as returning vacationers bringing back Japanese culture has greatly shaped how Japanese restaurants look and trade.

Economising the restaurant

Japanese restaurants now crowd the CBD. A quick look around Town Hall, and one will find at least four ramen shops, three JBBQ restaurants, two Japanese cheesecake shops, a handful of sushi bars, and plenty of other Japanese themed food vendors. While this may partly be explained as a holdover of the Japanese fine-dining history in the CBD, there are more critical factors that explain it.

As noted earlier, scarcity is the fundamental building block on which market exchange relies upon. In Social Justice and the City, David Harvey explains how spatial uniqueness and exclusivity confer an innate monopolistic quality. Within the CBD, monopoly rents can be extracted, as the land within the CBD is marked by proximity and accessibility that is unrivalled by any other part of the city. Thus, land value is extremely high, permitting only those uses that can afford such a high rent. To deal with the monopoly rents charged by landowners, those that wish to open a business within these areas require access to a large pool of capital.

Therefore, high revenue flow is key. And one way of achieving it is by tapping into the new exotic. Effective marketing capable of targeting the professional cosmopolitan class can draw massive lines. Ramen Auru is an example of this. Constantly posting on Instagram and attracting influencers, Ramen Auru were able to create a thirty-minute wait when I visited it, even on a cold Wednesday evening, just for a bowl of ramen. Auru’s marketing hinges on the liminal cultural space that Japanese cuisine inhabits, showing off their ticket machine and tatami seating again and again. This is further capitalised on by using premium products, up-charging for otherwise standard drinks by way of its association with the new exotic. No Japanese restaurant is immune from this, but Rara is a prime example of this phenomenon. Deliberate use of a brand-name Japanese whiskey, instead of a cheap alternative such as Jim Beam, underlines the mechanism through which restaurants justify charging higher prices. The camouflaging behind exoticism speaks to the exploitative nature of it all.

Both restaurants also exhibit another key characteristic that helps them survive — namely, their size. Businesses operating in Sydney’s booming property market can no longer survive as small independent stores. Expansion can be a solution to this, as it inevitably drives down costs through economies of scale, as well as creating a bigger pool of money on hand to use. Rara achieves this scale through a more conventional method of franchising. Their aggressive expansion to four stores allowed them to reduce the labour costs tied to food preparation. All their noodles are prepared at the spacious Randwick chain, saving on labour costs as a small team can reduce the amount of overlapping labour. Ramen Auru on the other hand, is more diversified in their restaurant strategy. The Hatena group operates one-off shops, selling products that do not overlap with each other, only unified by the Japanese theme at the core. In the face of rising expenses and soaring rents, Hatena group made the decision to amalgamate their finances and scale up the business. Streamlining back-end tasks like payroll, accounting and procurement provided the economic edge to maintain a competitive position in the market.

This dynamic is also prevalent within Sydney’s overall restaurant industry. Poetically likening themselves to Merivale’s CEO Justin Hemmes, who likewise owns a group of “independent” restaurants, Hatena aims to emulate his sprawling business strategy. Merivale’s pervasiveness in Sydney’s dining landscape highlights a hollowing of culture, following a pattern of Instagram-friendly, gimmicky environments coupled with over-priced food and beverages, such as Jam, a vinyl record bar. The “Hemmesification” is all too visible. The walls of stacked vinyls, just a prop to emulate the listening bars of Tokyo, are accompanied with Japan themed snacks and drinks. Hatena’s business model is no different, using props to evoke a sense of authenticity to justify their exorbitant prices.

However, ubiquity may produce an inauthentic experience for some. The relative failure of the Pacific Concepts group highlights the dangers of over-expanding. The “Disneyfied” products of Pacific Concepts, such as Fratelli Fresh and El Camino, highlight how, in David Harvey’s words, “the bland homogeneity that goes with pure commodification erases monopoly advantages.” Without a moderating institution or force to uphold a product’s uniqueness, the homogenising effects of scale will tend to erode monopoly rents. While Merivale and Hatena slightly diversify their products by not opening franchises, the shared language among their range highlights a potential flaw that can unravel their businesses. The conglomeration of the restaurant industry also risks a more acute punch to communities when the inevitable mass layoffs hit at once. Hatena and Rara are not unique in this regard, but only the latest symptom of businesses wringing out every last morsel of authenticity.

Shime

In 2015, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts launched the “Flirting with the Exotic” exhibit, centred around Claude Monet’s La Japonaise (1876). Patrons were encouraged to “channel their inner Camille Monet” during the “Kimono Wednesdays” event where attendees could try on a replica kimono and pose in front of the painting. Guests were further encouraged to post on social media with the “#mfaBoston!” tag. The event quickly attracted a protest movement of Pan-Asian locals, coalescing under banners such as “Stand Against Yellow Face” that aimed to push back against the orientalist tones of the exhibit. Many saw this event as contributing to the objectification of Asian culture, reducing Asian heritage to a costume. At the same time, counter-protestors — some of whom identified as Japanese — defended the exhibit as a case of “cultural appreciation, not appropriation.”

The exhibition was altered in light of the backlash — guests were no longer allowed to wear the kimono, just touch and feel the fabric. Tensions were not eased by the museum’s initial response, flatly denying the accusations of racism and orientalism without providing any substantive reasoning to back this statement. Dismissive comments from the outgoing director, and the fact that promotional materials like the “flirting with the exotic” title was not questioned by anybody during the design stage, point to the institutional racism that was undoubtedly felt by the protestors.

It may be easy to defer to Japanese opinion. Notably, the Japanese-ness of some of the counter-protesors had been highlighted, contrasting the Pan-Asian makeup of the original protestors. In just the same way, the ‘flanderisation’ of the ramen restaurant can often be enabled by Japanese people and institutions themselves. Ramen Auru’s largely Japanese employee base and management, Ippudo’s Japanese origins, the MAFF’s attempt to create the “Sushi Police”, all highlight the agency that Japanese entities have in shaping Japanese culture — for better or for worse. These situations highlight the unique position Japan occupies within discourse surrounding Asian representation. Japan sits “in, but above Asia”, and its fluctuating global image reflects its dominant history, while still undoubtedly being affected by orientalist tropes and anxieties. My own position as a Japanese-Australian person makes the dynamics of cultural appropriation and appreciation a vivid reality that I must navigate, and often grate against. While my Australian upbringing creates a degree of separation from Japanese culture, Japanese nationals also have largely not experienced the isolation of being a minority. Whether it’s the brutal history of Japanese internment camps (in America), or the suspicion of affluent migrants carrying the torch of ascendant Japanese industry during the trade wars of the 1980s, or the shadow of anti-Asian discrimination that has ramped up in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, these dynamics are not universally felt by Japanese nationals.

The La Japonaise controversy encapsulates so many of the features discussed within this essay. It is affected by the same conditions that have shaped the current form of ramen within the West. It is probably no coincidence that the “Looking East” exhibit — which La Japonaise was a part of — was conceptualised around the time of the Cool Japan Fund and Abenomics. Japanese culture has been moulded — by both the eager hands of enterprising nationals as much as locally-based business owners — into a premium product, warped to suit the tastes of ravenous consumers. Similarly, it has become all too clear that the “Kimono Wednesday” event was an attempt to commodify Japanese culture and boost attendance numbers.

The question of who can claim authority over a culture and engage with it is deeply meaningful. Can there be a genuine cultural exchange unmarred by the spectre of exchange value?

With Western palates increasingly steering the marketplace, tonkotsu ramen becomes ever thicker, blending in with the backdrop of a saturated, homogenising market. Popping into a ramen shop in Sydney today feels hollow — centred around gimmicks bordering on orientalism, with little in the way of meaningful depth. The proliferation of ramen as a dish throughout Australia has been so exciting to see. But with each new iteration, it’s becoming more and more difficult to enjoy a simple bowl of ramen. The magic of ramen, the colourful history, its breadth of regional styles and personality have been reduced to an unsavoury soup of bone extract.

Save for the art reproductions, all images are by the author.