On 29 October 2024, the Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus announced that the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights will conduct an inquiry into antisemitism on Australian university campuses. The referral to the Joint Committee on Human Rights follows a months-long process of determination by the Australian Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs that included the solicitation of public submissions and public hearings. It also follows the appointment of Special Envoy to Combat Antisemitism and the launch of an antiracism study into Australian universities by the Australian Human Rights Commission. Together, these measures are key pillars of a moral panic created by Zionist groups, and taken up by mainstream media and politicians, which responds to the upsurge of activities relating to Palestine on campuses in the past year. Palestine-related protests, public events, and teaching are deliberately cast as antisemitic to censor criticism of Israel and Zionism.

Activism led by students has focused on demanding universities divest from their relationships with weapons manufacturers arming a state engaged in genocide, disclose all ties to Israel, and commit to boycotting an apartheid regime. Eleven protest encampments were enacted at university campuses across the country, part of a global movement for Palestinian liberation grounded in anti-racist and anti-colonial principles. As the slogan goes: none of us are free until all of us are free. The actions of students have been mirrored by university workers who passed near unanimous motions through National Tertiary Education Branches across the country, including at the University of Sydney, the University of New South Wales, the University of Melbourne, and the University of Technology Sydney, which call for administrations to divest and join an academic boycott of Israel. In a move that reflects the rank and file sentiment across the country, a meeting of the NTEU National Council in October passed a motion in support of the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI) calling for a comprehensive academic boycott of Israel.

The inquiry emerges from intensification of political pressure that Zionist groups have directed toward the higher education sector since October 7. As our colleague Noam Peleg has outlined, such lobbying precedes the attacks of that day and has long focused on pushing universities to adopt the controversial International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism.

What makes the IHRA document controversial is the eleven examples that serve to illustrate it — seven of which conflate criticism of Israel with antisemitism. One illustration includes the phrase “denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, e.g., by claiming that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavor.” This implies the censorship of entire bodies of scholarly work in settler colonial studies, genocide studies, political philosophy, race studies and other disciplines that seek to unpack the colonial racial underpinnings of the Israeli regime and the Zionist project. The definition could also be used to suppress and negate discussion of the case brought by South Africa at the International Court of Justice that accuses Israel of violating the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide or the advisory opinion handed down by the same court on the illegality of Israeli occupation and on Israel’s discriminatory laws and measures legislation in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, which contravene international prohibitions on racial segregation and apartheid.

Australian universities, for the most part, recognised the threat of the IHRA definition to academic freedom and the campaign to have the IHRA definition implemented was largely unsuccessful, with most institutions taking the position that existing anti-racism policies covered antisemitism. In response, Zionist groups have sought to achieve policy change in universities by mobilising conceptions of antiracism, cultural safety, and psychosocial safety.

*

In advancing the IHRA definition of antisemitism, Zionists tapped into the language of antiracism, presenting the framework as an antiracist instrument that seeks to protect Jewish academics and students on campuses from antisemitism. But beneath the appeal to social justice lies a dangerous ideological move to characterise criticism of Israel (a state) and Zionism (a political ideology) as antisemitism (a form of racism against Jews). The conflation of Zionism with Judaism and, by extension, of antizionism with antisemitism aims to justify political repression in the service of protecting a colonial racial state. As Muhannad Ayyash has argued, the IHRA definition performs work to empower the censorship and repression of critical research, speech, and activism on Palestine by presenting Palestinian knowledge and epistemology as inherently antisemitic. It is a racial tool that enacts anti-Palestinian racism. Or, to borrow a formulation from Justin Podur, it is an example of a form of “racism that cloaks itself in anti-racism.”

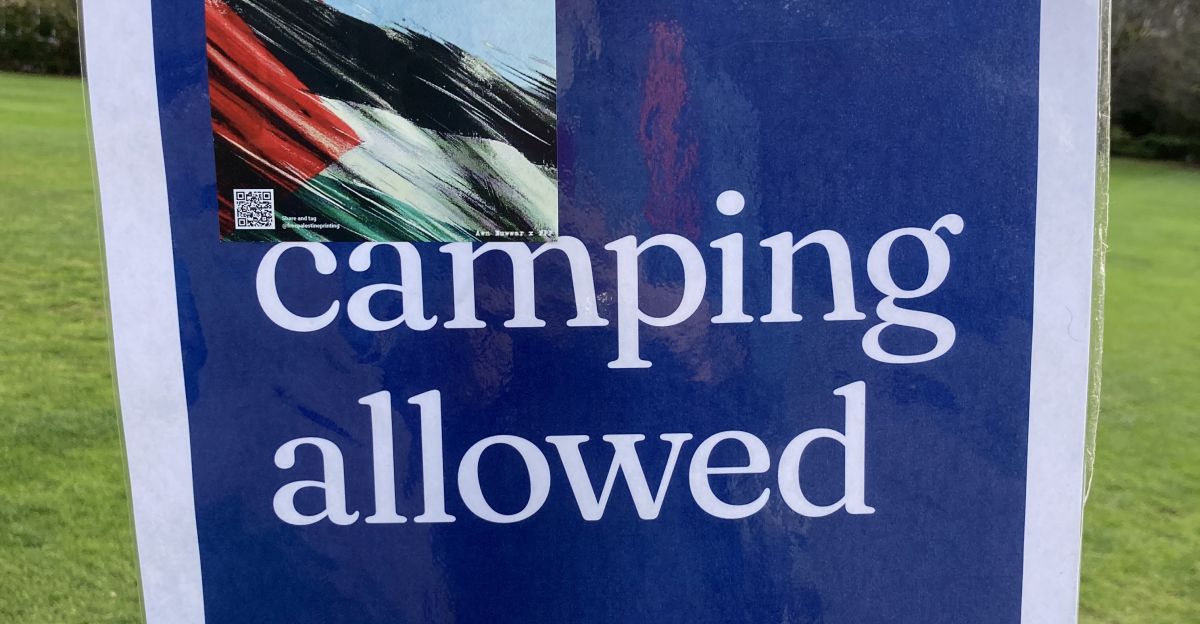

The appeal to antiracism is cynically used to cast all forms of critique and protest directed at the state of Israel as antisemitic. As the public submissions to the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs show, attributing settler colonialism, apartheid, and genocide to Israel is rendered inherently antisemitic. So, too, are displays of Palestinian cultural and political symbols such as the Palestinian flag, keffiyeh, and even the watermelon and red triangle symbols. The extension of this logic is that such things are framed as threats to the safety of Jewish people. But here we must reiterate the point that the suppression of signifiers of Palestinian cultural and political life is itself an example of anti-Palestinian racism. In a perverse evacuation of the principles of the antiracism, those who oppose colonisation, racism, apartheid, and genocide are cast as racists and as producers of antisemitism, which is seen in the West as an exceptionalist form of racism requiring exceptional protections. The danger of conflating legitimate critique of Israel with antisemitism is that it might obscure actual instances of antisemitism, the eradication of which remains the ambition of anyone committed to antiracist principles.

After October 7, appeals to cultural safety as justification for censorship on Palestine intensified, twisting the meaning of the term away from its original usage. Cultural safety, as Astrid Lorange and Andrew Brooks wrote in a recent issue of Overland, was a concept developed by Māori nurses and midwifery students to draw attention to the way things like colonisation can negatively impact health outcomes of Indigenous people and other minorities. For them, cultural safety was a call for healthcare workers to understand their own relationship to structures of power in order to denaturalise the presumption of universality and objectivity in public health systems. This shifted the question from what care is offered to how that care is provided. Beyond public health, cultural safety has become an important way to mitigate against the reproduction of colonial violence in order to create safe spaces for the continuation and flourishing of Indigenous culture and relations.

The Zionist mobilisation of cultural safety inverts the term’s original intent by emphasising individual feelings in ways that obscure the material and collective realities of invasion and occupation. As Randa Abdel-Fatah has succinctly put it: “The feelings and fragility of Zionists are used as a rhetorical shield to deflect from the reality of Palestinian genocide.” In the name of these feelings, politicians and university administrators are being asked to clamp down on all forms of opposition to Israel and Zionism.

The opening of the Commission of Inquiry into Antisemitism at Australian Universities Bill 2024 (No. 2) by the Australian Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs signalled a strategic shift from the rhetoric of cultural safety to that of psychosocial safety. The latter category, which emerged from psychological and sociological discourses to describe the way social environments can produce psychological trauma, has come to be enshrined in Workplace Health and Safety Acts across the country.

Safe Work Australia, the Australian Government Agency tasked with positively improving working conditions and workplace cultures, articulates a psychosocial hazard broadly as “anything that could cause psychological harm.” The term was originally used to challenge some of the narrow individualistic and intra-psychic frameworks that dominated psychological discourses by encouraging attention to the way structural violence can produce ongoing psychic harm and injury. The union movement took up the concept in a bid to protect workers from exposure to sustained and recurring forms of workplace stress that, over time, could produce harms such as anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, sleep disorders, and so on. While the category has a necessary elasticity to it, commonly identified psychosocial harms include such things as: excessive and unsustainable workloads, low job control, lack of role clarity, the absence of appropriate training and support structures, poor organisational justice, inadequate recognition mechanisms, degraded physical working environments, bullying and harassment, experience of traumatic events, or the exposure to violence and aggression.

The attempt to render critiques of Israel and pro-Palestinian activities as causes of psychosocial harm once again turns a framework intended to protect those vulnerable to systemic and structural ills against itself, opening the door for such activities to be repressed under the Workplace Health and Safety legislation. Where the mobilisation of cultural safety sought to claim the moral position of victim, the turn to psychosocial harms seeks to tacitly enshrine Zionism as a protected identity in legislation. When claims of antisemitism fail to register with universities (for example, universities in this country mostly did not accept that labelling Israel an apartheid colonial state is antisemitic as the IHRA definition seeks to advance), then the language of safety and psychosocial harm — and its focus on feelings rather than actual safety — is leveraged to do the work of censorship, silencing, and political repression.

Psychosocial harms to be censored in the name of Zionist feelings include criticisms of Israel, protests against Israel, solidarity with Palestine, speaking of Palestinian liberation, teaching about Palestine (especially in relation to Israeli colonialism, apartheid, and genocide), the visibility of Palestinian cultural and political symbols, and public events on Palestine. To be clear, none of these examples should be understood as psychosocial hazards. Rather, they are things that make Zionist supporters of Israel uncomfortable. Accepting these as legitimate causes of psychic harm sends the message that the discomfort of Zionists trumps the material realities of a genocide, as well as the scholarly and political movements that allow us to make sense of, and oppose, that unfolding reality.

The claim that legitimate critique and political contestation contravenes psychosocial protections opens the door to contesting the way these things are currently protected under university policies and Enterprise Bargaining Agreements. In response to the public scrutiny generated by recent parliamentary inquiries, universities have begun to declare their commitment to psychosocial safety every time they mention academic freedom — balancing the two principles against each other. Take, for example, the statement made by Sydney University Vice Chancellor, Mark Scott at the recent Senate Hearings:

we were trying to balance our obligations to ensure the health and safety – including the psychosocial safety – of the entire diverse university community, with our commitments to academic freedom and free speech.

But the balance has already tipped against academic and political freedoms, with a serious escalation in the repression of Palestine-related activities by university administrators since the initial inquiry. Universities, capitulating to Zionist and political pressure, are threatening to dismantle core principles of academic freedom and the right to protest. Rather than protecting staff and students against McCarthyist attacks, universities are using administrative measures, and introducing new ones, to limit Palestine related activities on campus in the name of psychosocial safety. In doing so, universities are creating an environment of intimidation designed to create a chilling effect among students and staff.

*

Over the past months, we have seen a sharp rise in misconduct charges being brought against students and staff critical of Israel and Zionism. Universities have been abusing the fact that misconduct investigations are confidential and are weaponising this confidentiality against students and staff who cannot reveal these investigations publicly. Often, as we know from other struggles, the ability to leverage public pressure against universities is one of the most effective lines of defence against political targeting, especially given that misconduct committees lack any recourse to external mediation and so are shrouded in opacity or open to orchestration to achieve desired outcomes. Given that these investigations are confidential, we don’t have a precise estimation of the phenomenon. That said, we do know of dozens of current cases and the real numbers are likely to be higher.

Academics have also been called to meetings with their Deans, Heads of Schools, and line managers over their involvement with Palestine activism. Other limitations placed on academic freedom include altering law exam questions on International Court of Justice rulings and advisory opinions on Palestine in the name of psychosocial safety, scrutinising or censoring reading groups, cancelling academic events featuring Palestinians or that are critical of Israel, subjecting events on Palestine to extensive risk assessment procedures, and instructing students not to speak about Palestine in classrooms.

Freedom of Information requests have been used to harass and intimidate academics active on Palestine across multiple universities around the country, as well as by Zionist groups to target Australian Research Council-funded projects authored by scholars critical of Israel. Such requests are another technique of intimidation designed to apply public pressure to politically engaged scholarship. In the case of the Palestinian academic and writer Randa Abdel-Fattah, there was — and remains — concerted attempts by Zionist groups, the media, and politicians to get her fired from her position at Macquarie University and strip her of the prestigious Australian Research Council Future Fellowship grant. The filing of racial vilification complaint through the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) against the University of Sydney and two of its academic staff members — Nick Riemer and John Keane — constitutes yet another attempt to conflate critique of Israel with antisemitism, a claim that must be vociferously contested every time it is made. Riemer, a long-standing Palestine solidarity activist and a key figure in the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement at the University of Sydney, offered this response:

This complaint is a vexatious abuse of the AHRC. It has no other aim than to discredit opposition to genocide, and takes the commission away from its real work of fighting actual discrimination.

Universities are also directly targeting student activism, through measures that include: the suspension of pro-Palestine student associations and clubs (for example, Students for Palestine at UNSW have been suspended by student body Arc); restrictions and prohibitions on political postering, flyering, and chalking on campuses; attempts to prohibit the use of the world genocide in relation to Israel; and even the shutting down of a student-run bake sale to raise funds for Gaza. To try and limit protests on campus, universities such as Sydney University and UNSW introduced new campus policies that now require protest organisers to give 48 hours’ notice of their planned action as well as stringent new risk assessment procedures that ask organisers to mitigate against all possible psychosocial harms (with all the ambiguity that this term now carries with it). These policies act as a form of deterrence as students and staff who sign the risk assessment forms can be held accountable for any “inappropriate” occurrence or anything that has the potential to trigger harm (actual or manufactured, mostly the latter).

Universities have been treating Palestine activism as a threat and through a criminalised and securitised lens. Western Sydney University called-in police and riot police to dismantle a student sit-in in solidarity with Palestine resulting in the use of undue force on students and staff and in the arrest and suspension of several students. Western Sydney University placed police, campus security, private security, and metal detectors at a recent graduation ceremony in a move that turned students, their families and the community in Western Sydney – many of whom are Arabs, Muslims, and people of colour – into a threat. The Vice-Chancellor of the Australian National University, Genevieve Bell, revealed to a Senate Estimates Committee that the university spent almost $1million on security and surveillance in response to the solidarity encampment before evading questioning from Greens Senator Mehreen Faruqi as to whether the university engaged private investigators or consultants to monitor student protestors. And at UNSW, the university found it appropriate to have security with body cameras filming a peaceful staff vigil to mark a year to the genocide as part of the NTEU Day of Action on Palestine. Poetry, it seems, is also a threat.

In response to the intensification of repression on university campuses across the world, Gina Romero, Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, urged universities to act immediately to ensure and protect the right to protest peacefully on campuses in the context of international solidarity with the Palestinian people. Romero’s report examined campuses across thirty different countries, concluding that “the brutal repression of the university-based protest movement is posing a profound threat to democratic systems and institutions.” Some of the concrete recommendations included in the report include calling on universities to:

actively facilitate and protect peaceful assemblies; … refrain from and cease any surveillance and retributions against students and staff for expressing their views or participating in peaceful assemblies; … ensure transparent and independent investigation into human rights violations that occurred in the context of the camps and other peaceful assemblies, revoke sanctions related to the exercise of fundamental freedoms, and provide effective and full remedies to affected students and staff.

As we write this piece, the genocide in Gaza and Israel’s war on Lebanon continue. Northern Gaza is being carpet bombed and starved — two hallmarks of ethnic cleansing. Before this essay goes to print, countless more lives will have been claimed, more infrastructure required to sustain life and culture will be destroyed, and the humanitarian catastrophe will continue to escalate. The lives taken are those of children, brothers, sisters, parents, colleagues, comrades. In the face of genocide and apartheid, the Federal Government’s response has not been to impose sanctions on Israel, but rather to open a parliamentary inquiry into antisemitism on campuses that acquiesces to the political pressures of Zionist lobbying and empowers university administrators to repress pro-Palestinian activism under the guise of safety and inclusion.

The global movement for Palestinian liberation has shown us across the past year that we have the collective capacity to endure waves of repression. Now is the time to turn that capacity toward defiance.

Image: @freepalestinegeelong, from a demonstration at Deakin University in April this year