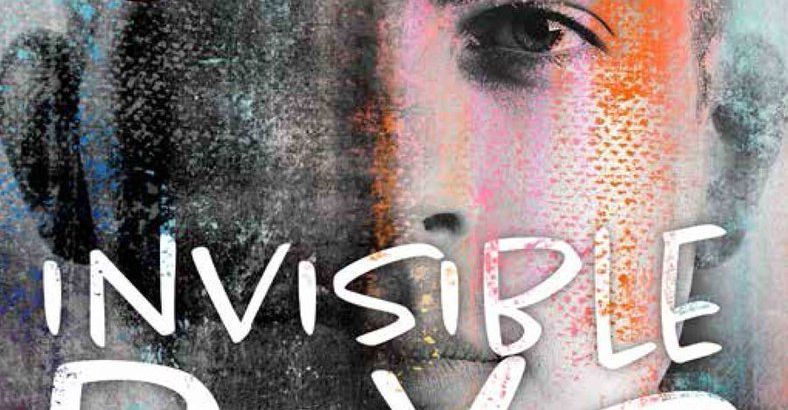

Holden Sheppard’s Invisible Boys — lately in the news for its TV adaptation on Stan — is an imperfect but extremely entertaining novel that deserves its success. I argue that it is a canonically important work of Australian gay literature, a monument of eroticised and anxious masculinity belonging to a legacy including titles such as Christos Tsiolkas’ Loaded and Barracuda, or Tim Winton’s Breath. I also argue it impeccably instantiates some important gay sexual archetypes, with one major omission.

To dispense briefly with some points regarding young adult fiction, of which I am no expert, Invisible Boys is well-written but suffers from the literary trope of emotional overdetermination. The teen protagonists experience emotions that arrive, fully formed and articulated, immediately following the events that trigger them. They leave no time to process, no self-doubt or disbelief. They handhold the readers through these emotions, reminding them, usually needlessly, that they should feel them, too. A major example of this is the villainous Catholic school principal Brother Murphy arguing to Charlie that his misbehaviour at school amounts to his “pissing on the legacy” of his dead father — an event so garishly loathsome that we hardly require Charlie’s subsequent exhortations about how upset he was that it occurred. In Invisible Boys, we are in a primary-coloured, block-shaped moral and emotional universe. But these are insipid criticisms: just as it is silly to go down the rabbit hole and complain about finding rabbits, it is silly to read a YA novel and complain that it was, in fact, YA fiction.

Invisible Boys tells a fantastic story. For its tight form and pace, I admire it. I use the term fantastic to mean that it is arch melodrama, anchored by narrative and emotional events so preposterous as to verge on soap opera camp. Nerd Zeke’s secret relationship with jock Hammer is straight out of American teen drama (from a playbook including Cruel Intentions and Glee), and we know as an audience to suspend our doubt that this might ever really occur. As for Charlie Roth, Sheppard marches him through a carousel of ceaseless cruelty at the hands of almost every character bar Zeke and Matt: callously outed by a scorned local woman, he becomes widely ostracised in the conservative Geraldton community; his mother and his stepfather openly mock him both in private and public; he is ritually humiliated, Carrie-style, at his school dance; and when he gives in to the crowd’s screams to kiss Hammer on stage, he is promptly expelled from school. The final punishment that the Marquis de Sheppard inflicts on Charlie is the suicide of his secret boyfriend, farmboy Matt Jones, following a tiff between the two that crystallises the latter’s belief that he would rather be dead than gay.

Indeed, the novel’s final act (centring around Zeke’s brother’s wedding and its aftermath) feels like an apocalypse. Charlie and Zeke accept that their lives have irreversibly changed, while Hammer remains in denial. There is a small glimmer of hope for all three, but the threat of impending disaster far greater. In many ways, these unsubtle extremes are part of Invisible Boys’ great merit: they evoked feelings in me that reminded me of being a teenager. Secret desire, righteous fury, profound loneliness, the thrill of one’s fantasies becoming real, the urge to run away from it all. For me, these were euphoric and not entirely welcome feelings. In this respect, Sheppard did a commendable job.

Invisible Boys may be a YA novel, but it is also, intentionally or otherwise, a work of softcore (and sometimes hardcore) pornography. In the novel, two major erotic fantasies are realised, which both feature sexual archetypes well canonised in gay culture from Frank O’Hara to Tom of Finland to the Village People. Firstly, there is the fantasy of the nerd getting with the jock. The term “jock” may be an American cultural import, but the concept of a sporty alpha male certainly exists in Australian culture in its own right, and Kade “Hammer” Hammersmith fits the bill (even that name is pornographic). It is well known as not solely an archetype in teen media, but also in pornography and even as a personal identifier on hookup apps for men. Secondly, there is the fantasy of the punk getting with the farmboy. “Farmboy” is a blue-collar archetype, cousin to the construction worker, the lumberjack, the cowboy, and so on. Like the “tradie”, perhaps we can claim the “farmboy” as an Australian contribution to the gay cultural canon (see also Lonesome (2022)); if so, let us thank Sheppard for documenting the archetype so beautifully and sadly in the form of Matt Jones.

One canonical gay sexual archetype is missing from Invisible Boys: the twink, the sissy, the femboy, in other words — the effeminate young man. Invisible Boys is a love letter to masculinity, of which Holden Sheppard is clearly a scholar. It is a West Australian masc homosexual fantasia of a world containing only manly men, which the masterful Nic English audiobook performance captures perfectly — from the footy dickheads at school to the senior Italian gents bottling tomatoes to an endless series of stern, disapproving fathers. Sheppard recognises that the vernacular and humour of the true-blue Aussie bloke is one of Australia’s richest cultural wellsprings (which has blessed us with the swagman, the larrikin, the jackaroo, Crocodile Dundee and even The Betoota Advocate).

However, masculinity is not merely an aesthetic principle in Invisible Boys, but a moral principle. Its absence in men is reviled by every character in the novel, straight or gay, man or woman. It is the measure of a man’s honour and success, a quality that trumps all others. It goes without saying that jock Hammer and farmboy Matt are masculine and are esteemed as such. In this respect, they conform to type. But even punk Charlie and nerd Zeke are masculine in their nature, mannerisms, and instincts. Charlie rushes to correct people when they jibe at his painted nails: “It’s a punk thing.” Zeke, who envies his alpha male older brother and hides his masturbation habit from his overbearing parents, might as well be an Italian-Australian Alex Portnoy. For these four characters, the overarching conviction is not “being gay doesn’t mean I can’t be a man,” it’s “being gay doesn’t mean I can’t be masculine.” Their greatest fear that if they come out, their community will see them as effeminate sissies (and it’s true — they will).

Masculinity is an important and controversial topic in gay discourse, and Invisible Boys should be celebrated as an excellent document of the phenomenon as lived in regional Australia. Yet I lamented the absence of an effeminate gay character in Sheppard’s macho universe. A character for whom painted nails might not have just been “a punk thing”. (For the record, there is one: a debauched and odious urbanite guest at the hotel where Hammer is staying, who sexually aggresses upon Hammer despite the latter’s obvious adolescence, and reacts with hostility when a threat of exposure makes Hammer recoil.)

Invisible Boys is a fantasy, but it reminded me of the painful and enduring truth that effeminacy in men, both straight and gay, remains vilified and contemptible in our culture, considered both an aesthetic stain and an indicator of feeble character. How might a sissy young man (a hairdresser? a receptionist? a cashier?) have endured the machismo hostility of Invisible Boys’ Geraldton? With full respect to Charlie, Zeke, Hammer and Matt, such a boy might have needed more bravery than they did, brave though those boys variously were. Unlike those boys, a sissy boy wouldn’t live with the fear of his community seeing him as something that he is not; rather, he would live with the shame of his community seeing him as something that he is. Ultimately, this boy’s story may simply not have been Sheppard’s story to write. The story Sheppard wrote is about invisible boys, but a sissy boy in that world, for better or worse, could not have been but visible.